After Councilmember Kenyatta Johnson was indicted this week, a lot of the follow-up analysis has rightly focused on the much-criticized practice of councilmanic prerogative—an unwritten tradition where members defer to District representatives on local matters.

Sean Collins Walsh points out that Johnson, who was indicted for an alleged abuse of his zoning powers, was chosen by Council President Darrell Clarke to be the most powerful person on Council in charge of zoning as head of the Rules Committee. And Bobby Henon, who was indicted for offenses involving L&I, was given the chairmanship of the L&I committee by Clarke.

Jake Blumgart asked members of Council whether they thought it was time to reevaluate the councilmanic prerogative tradition in light of Councilmember Johnson’s indictment, but several members were undeterred, including Mark Squilla and Cherelle Parker.

Squilla unfortunately brings out the tired “unelected bureaucrat” straw-man, which elides the fact that the mayor—a democratically elected official who is elected by a much larger number of voters than anybody—presides over the Philadelphia City Planning Commission, L&I, the Zoning Board, and other related boards and commissions.

“When you have a bureaucrat making these decisions, they don’t have to answer to anybody,” said Councilmember Mark Squilla. “Who would you rather have representing you, someone you can vote for or against every four years, or someone over whom you have no say, and they can do whatever they want?”

Philadelphia’s district councilmembers are rarely challenged in a meaningful way in either primary or general elections, however. Neither Squilla nor Parker faced any real competitor in reelection bids in 2019. Johnson won his last three elections squarely, despite challengers in the last two primaries.

The only district councilmember who did lose re-election last year was West Philadelphia incumbent Jannie Blackwell, who was defeated in part because of voter concern over her handling of land use issues.

New 3rd District Councilmember Jamie Gauthier, who is an urban planner by training, had a smart counter to this, as did At-Large Councilmember Helen Gym, who recently broke with prerogative norms to vote against the Drexel food truck ban at the end of the last term.

“When you have this tradition where you are almost solely abdicating issues around land use and land disposition and zoning to one person, I think it’s kind of ripe for misuse or even just the appearance of misuse,” said Gauthier.

District members’ opinions should be heavily weighted in such decisions, Gauthier said, because they know their areas the best. But she said that the city needs a stronger check on councilmanic prerogative, especially when it comes to major decisions like the city’s plan for 4601 Market St. in her district. There, a major land deal was mysteriously held up for months by her predecessor—at the behest of a developer ally, it turned out.

“I think the administration has to provide a check on proving why these recommendations are made, especially when you are dealing with donors or family members who might have connections with parties involved in projects,” said Gauthier […]

“I do think that the city has ceded its authority to council, which isn’t equipped to review every single small thing that goes through a councilmanic district,” said Gym. “It is incumbent on the city to enact a set of rules that could balance out any concerns about overextension in any particular area.”

Everybody can point to an instance where councilmanic prerogative has come in handy in a pinch, but it also has a tendency to place members at the center of lots of deals they shouldn’t be a part of, illegal or not.

As of 2015, according to a Pew report, all six members of Council convicted of a crime since 1981 committed offenses related to councilmanic prerogative, so it’s clear that it has a certain pull. (Johnson, if convicted, will be a seventh.)

![]() Contra Councilmember Squilla, there are some great reasons to prefer that the Planning Commission should have the last word on land use legislation, by making their recommendations binding just like the Art Commission’s are.

Contra Councilmember Squilla, there are some great reasons to prefer that the Planning Commission should have the last word on land use legislation, by making their recommendations binding just like the Art Commission’s are.

Here are four reasons why giving Planning a real veto would be an improvement for housing policy outcomes and politics—and wouldn’t be as bad for Councilmembers as some think.

1. Clubby norms mean things wouldn’t be that different

On a few notable occasions in Mayor Kenney’s first term (most recently with the Society Hill bike lane feud) he’s avoided taking actions that he had the power to do administratively, but did not in order to avoid crossing the local Councilperson.

The professional norms seem to push everybody in the direction of the councilmanic prerogative logic, even when it concerns things that the mayor can do administratively.

For the Councilmembers worried that the end of councilmanic prerogative would mean important district decisions being made without their involvement, it’s just impossible to imagine.

For those of us dying to see a more muscular Planning Commission, the sad truth is that things probably wouldn’t work all that differently. It’s inconceivable that any truly important decisions would be made without strongly considering the District Councilperson’s view.

2. Most land use business is boring

To Councilmember Gym’s point about Council being poorly “equipped to review every single small thing that goes through a councilmanic district” the councilmanic prerogative system makes Council waste way too much time on inane stuff that could just be done administratively, like approving outdoor café seating or planters.

Because of all the different areas of regulation and permitting that have been added to the ever-growing scope of councilmanic prerogative, about one in four bills now deals with these kinds of small-ball issues, according to reporting from WHYY reviewing 15,000 Council bills.

Many of these hyperlocal bills involve zoning tweaks, parking regulations and minor street alterations. Council is required by law to pass a resolution to sell a piece of city land: that accounted for 1 in 10 pieces of all legislation, the analysis found.

Some of the matters that fall under prerogative are minor, yet City Council approval is required to open a newsstand—94 bills, for example — or erect a sidewalk cafe (41). Members can act to ban food trucks or vendors from a block of their district, or from the whole thing, as Brian O’Neill did earlier this year.

For the vast majority of these kinds of bills, there’s nothing controversial to decide. But some Councilmembers prefer to have this huge workload of mundane bills just so they can swoop in to broker the relatively small number of controversial cases.

That’s a bad trade-off for members, and having watched several of these types of cases play out in my own neighborhood, it often seems like having the power to intervene in some of these neighborhood controversies ends up doing political damage to Councilmembers equally as often as there’s a political upside.

Wouldn’t it be nicer to be able to deflect to the mayor more often when people are upset about zoning, and avoid getting roped into some of these neighborhood skirmishes?

3. The mayor has the right incentives to do what’s in the broad public interest, while small, vocal groups rule Council’s world

Prerogative defenders would like to frame this issue as elected officials versus bureaucrats making decisions, but really it’s about which elected official is the right person to make the decision about any particular topic.

When it comes to land use and planning issues, where all kinds of high-level city![]() goals for affordability, sustainability, mobility and more hang in the balance, the best person to make those decisions are the elected officials best able to keep these major citywide priorities in perspective, and balance them against the need for some local accommodations along the way.

goals for affordability, sustainability, mobility and more hang in the balance, the best person to make those decisions are the elected officials best able to keep these major citywide priorities in perspective, and balance them against the need for some local accommodations along the way.

That doesn’t mean the mayoral administration is inattentive to the small details. Planning Commission staff have geographic focus areas too, and are part of the same conversations as Council around zoning much of the time, or L&I or Streets staff in the case of some of the other councilmanic prerogative areas like sidewalk seating and planters.

Because of all the different areas of regulation and permitting that have been added to the ever-growing scope of councilmanic prerogative, about one in four bills now deals with these kinds of small-ball issues.

The difference is the mayor and his staff are able to keep the broad citywide public interest in perspective, while City Council District members have a much narrower vantage point on what matters, because of their small geographic districts.

The people who participate in zoning and planning tend to be generally older, whiter and more privileged members of the community. They also tend to disproportionately oppose housing, according to some interesting research in the new book Neighborhood Defenders, which studied participation in neighborhood zoning meetings across the Boston area.

Anecdotally, this is also a pretty common public meeting dynamic in Philadelphia, and it raises some real questions about whether the Registered Community Organization review process for zoning variances is actually useful for giving Council and the Zoning Board of Adjustment good information about the community’s sentiment about planning issues if the people participating are so unrepresentative of their neighborhoods.

This is the kind of distorted picture Council is getting about the issues that prerogative typically touches on.

A perfect example of how Planning could counteract the worst excesses of that kind of political dynamic is their pocket-veto of the Society Hill rezoning bill at the end of last term.

Councilmember Squilla introduced a pretty unfortunate rezoning bill on behalf of Society Hill Civic Association that Planning Director Anne Fadullon criticized as “exclusionary,” and Planning had the rare power to stop it because it was the end of the term.

We would get more balanced outcomes if Council could introduce the bills, and Planning could have a veto option in order to temper how parochial things can get.

4. The 2035 District plans have the most democratic legitimacy

The other main argument for the mayoral administration to have more influence over traditional prerogative topics, particularly in the area of zoning, is that the Planning Commission’s comprehensive plans have a lot more democratic legitimacy than what happens at RCO meetings.

The Planning Commission just completed a citywide comprehensive planning process for all 18 planning districts in Philadelphia, and each of these plans involved significant public participation by hundreds of people—many more than local zoning meetings tend to attract and with a much more representative public.

Everybody can point to an instance where Prerogative has come in handy in a pinch, but it also has a tendency to place members at the center of lots of deals they shouldn’t be a part of, illegal or not.

At these meetings and other avenues for participation that were part of the district planning process, neighbors in different regions of the city weighed in on the big-picture goals and values for their regions—each about half the size of a Council District.

Each of the plans came with zoning recommendations for the entire area, across multiple neighborhoods, offering a wider and more appropriate lens for thinking about things like where growth should be directed.

This is the most valuable kind of public feedback, and the larger number of participants involved means it should carry more weight as a guiding force on zoning questions than the type of reactive politics that councilmanic prerogative encourages.

The Planning Commission is much more suited to properly weighting these democratically-chosen planning goals in the course of making day-to-day decisions.

Jon Geeting is the director of engagement at Philadelphia 3.0, a political action committee that supports efforts to reform and modernize City Hall. This is part of a series of articles running on both The Citizen and 3.0’s blog.

The Fix is made possible through a grant from the Thomas Skelton Harrison Foundation. The Harrison Foundation does not exercise editorial control or approval over the content of any material published by The Philadelphia Citizen.

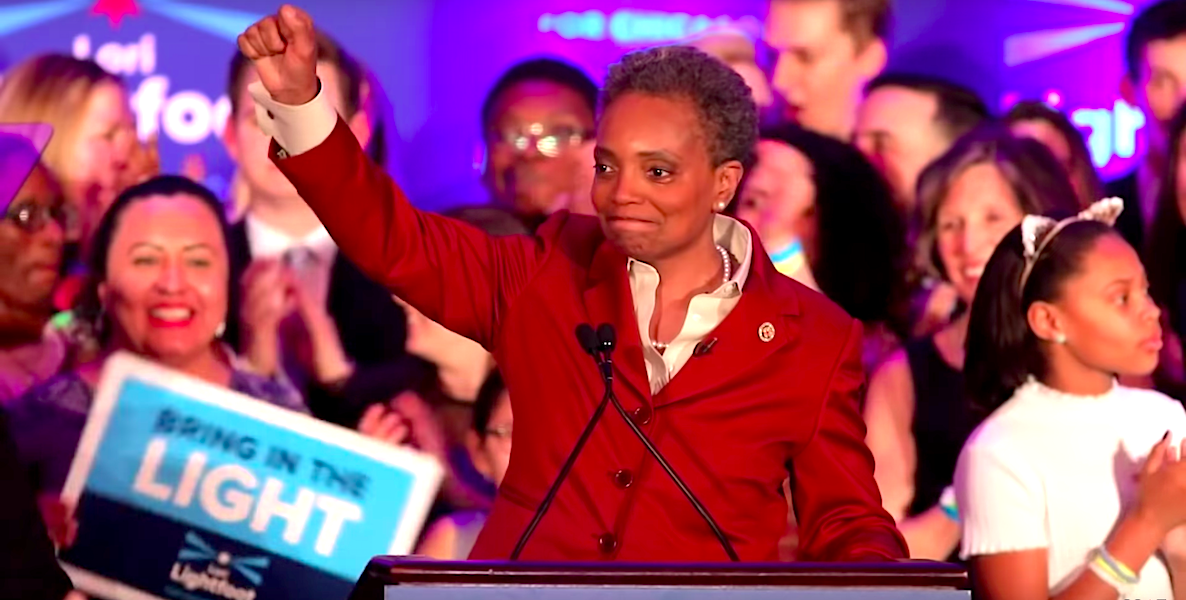

Header photo courtesy Jared Piper / Philadelphia City Council