Walk through Philadelphia’s City Hall on any given day and you are bound to encounter someone whose life was irreparably damaged by gun violence.

In the first regular meeting of City Council this year, Councilwoman Katherine Gilmore Richardson told the assembly that her cousin had been killed the weekend prior. Someone shot the man on the front steps of his North Philadelphia home during an attempted robbery, Gilmore Richardson told her colleagues, saying the city is in a “state of emergency.”

A few weeks later, Councilman Kenyatta Johnson—who became politically involved after the 1998 murder of his cousin—convened a meeting for Philadelphians to talk about the impact that gun violence has had on their lives.

Cherie Ryans showed up clutching an image of a Tec 9, the type of gun used by a group of assassins who killed her son and his best friend as they were leaving a West Philadelphia movie theater on Labor Day weekend 1990. The killers, who all escaped punishment, had been targeting someone else in the car, according to Ryans, who said hardly a day goes by when she doesn’t cry about the loss of her 18-year-old child.

Read the quick version of this story. Short on Time?

Philadelphia can only do so much on its own, and the city can hardly do anything when it comes to regulating the hardware used in so many murders. Guns were used in all but six of the 38 homicides in January 2020, according to the police department.

While legislation attempting to deal with the problem is jammed up in Harrisburg, City Council is taking a litigious approach towards state lawmakers. The legislative body authorized itself to hire attorneys to sue the state to try to compel it to enact new more restrictive gun laws or grant Philadelphia the power to do that on its own.

City government is much less powerful than state government, and Pennsylvania state law pretty comprehensively bans its cities from creating their own gun ordinances through what is known as the Uniform Firearms Act, so success in court seems like a long shot. But setting aside the legal arguments, Philadelphia’s lawsuit would be an expression of political leaders’ frustration with Harrisburg’s chokehold on gun laws.

“Every major movement throughout history started off with individuals in high places saying no,” says Johnson. “You can’t just be silent and say, ‘Well we don’t have the votes. We’re just going to be quiet.’ We can’t just sit back and say, ‘Well they have state pre-emption and so we’re not going to sue them.’ So if it was me, we should sue them every year to keep our issue on the forefront.”

City government is much less powerful than state government, and Pennsylvania state law pretty comprehensively bans its cities from creating their own gun ordinances through what is known as the Uniform Firearms Act.

Philadelphia is hardly alone in chafing against the state’s prohibition on local gun ordinances. Pittsburgh passed its own gun ordinances last year, and was promptly sued by Firearm Owners Against Crime and other gun groups. The city lost its case in the Court of Common Pleas late last year and has appealed to the Commonwealth Court.

The policy goals of Philadelphia’s forthcoming lawsuit are not yet specific, but there are a few ideas bouncing around Harrisburg that may be able to gain traction.

“The goal is to allow us to have the opportunity to protect our citizens. What ultimately that will be in terms of the specific legislation—I’m not clear,” said City Council President Darrell Clarke last month. “But right now you have a general assembly and a Commonwealth of Pennsylvania that won’t allow us to do anything.”

The path Council is taking to court diverges procedurally from the course laid out by the City Charter. The charter says Council should obtain legal services from the Law Department “exclusively,” except when the Law Department has declined to provide legal services or in circumstances that involve investigating the executive branch of city government.

About gun legislationLearn More

Clarke has been down this path before; he lost in court more than a decade ago, but the political makeup of the state’s highest court has shifted to the left since then. Back in 2007, he argued that under existing law Philadelphia ought to have the right to chart its own course on gun regulations, and therefore seven gun ordinances passed by Council should take effect.

This time around, Council is trying to put the “obligation to protect the citizens of Philadelphia” on state lawmakers and force them to pass new gun laws—either giving Philadelphia more autonomy or creating new state regulations.

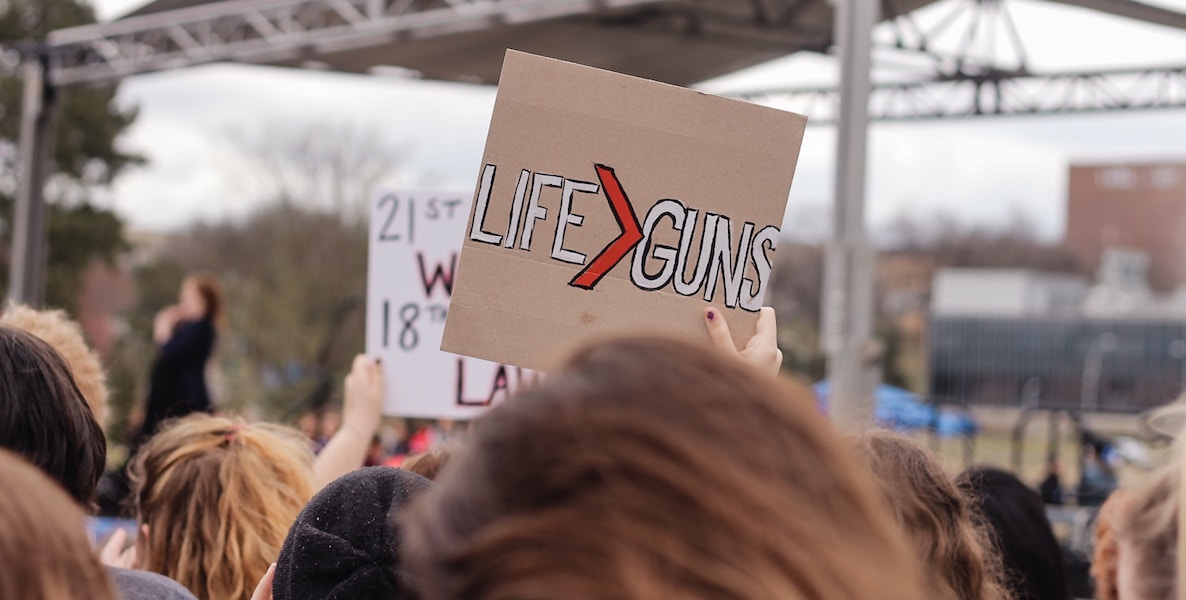

The litigation in Pittsburgh, and the burgeoning lawsuit out of Philadelphia, add to the clamor from some corners for tighter gun restrictions. Two Democratic state lawmakers from Pittsburgh said the legal action could help them in the legislative arena if it helps draw more attention to the issue.

“From my standpoint, it’s effective in shedding light on the dilemma that our local governments—particularly cities that are most affected by gun violence—have. And if it helps to mobilize the public and stakeholders into putting pressure on the legislature that’s great,” says Rep. Dan Frankel, a Pittsburgh Democrat who has spent two decades pushing for tougher gun laws. “My colleagues respond to political pressure that mobilizes voters more than anything else, and if that effort helps toward that, I’m all in favor of it.”

In the House, Rep. Rob Kauffman, a Franklin County Republican, holds the controls of the Judiciary Committee—where gun bills tend to be introduced—and last year Kauffman said the committee would not consider any more gun measures. Kaufman did not respond to a request for comment, but Mike Straub, spokesman for the House Republican Caucus, says House Republicans recognize that gun violence is a major problem.

“House Republicans absolutely agree, gun violence is a devastating problem plaguing several communities across our Commonwealth. We will continue to work towards policies that reduce violent crime,” says Straub.

The House Republicans’ approach, however, is to focus on punishing people who are caught committing gun crimes rather than the policies favored by Frankel and others that would put tighter controls on access to guns.

“One thing we should all agree on is that people convicted of violent crimes with a firearm belong behind bars,” Straub says. “However, in the vast majority of current sentences imposed on criminals who used a firearm in committing an offense, the sentence was below state sentencing guidelines.”

Others contend that state laws should be crafted to prevent guns from winding up in the hands of those likely to use them to harm themselves or others. In 2018, that side won a rare victory.

That year Pennsylvania lawmakers passed a new statute to take guns out of the hands of domestic abusers, the first gun legislation in the state in more than a decade. Frankel said the key to getting that bill over the finish line was that the proposal had true bipartisan backing, members felt political pressure in their districts to deliver some results on the issue, and groups such as CeasefirePA and Moms Demand Action were a consistent presence at the state capitol.

On the other hand, an Extreme Risk Protection Order bill introduced last year by Montgomery County Republican Rep. Todd Stephens that has proven to reduce suicides in several states, failed to even make it out of the judiciary committee last year.

“You can’t just be silent and say, ‘Well we don’t have the votes. We’re just going to be quiet.’ We can’t just sit back and say, ‘Well they have state pre-emption and so we’re not going to sue them.’ So if it was me, we should sue them every year to keep our issue on the forefront,” says Councilmember Johnson.

While Republicans tend to have a more laissez-faire approach to firearms and Democrats tend to be more on the side of restricting access, an official in the House Democratic caucus said that opinions on gun legislation don’t neatly follow party lines. There is a “regional breakdown” among Democrats, where members from more rural districts are more reluctant to restrict access.

Senate Minority Leader Jay Costa, a Pittsburgh Democrat, says the Senate tends to be more amenable to gun-control bills, and he thought Kauffman’s stonewalling in the House committee is “inappropriate.” While it’s hard for anyone to say much about Philadelphia’s litigation since the arguments haven’t yet been spelled out, Costa, a lawyer, says the City could potentially have a valid case.

Three ways to get involved on this issueDo Something

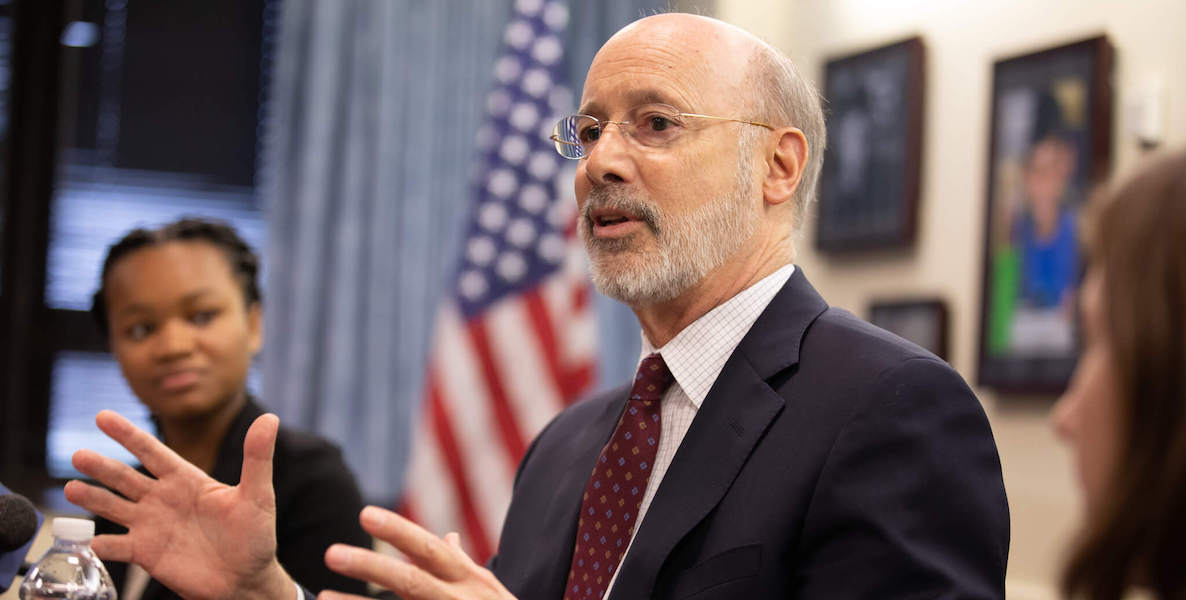

The ideas backed by gun control advocates such as Costa and Frankel roughly match what Gov. Tom Wolf proposed in his annual budget address. The governor, a Democrat, called for requiring background checks for everyone buying a gun, stricter requirements for gun owners to report when a weapon is stolen, and a system for confiscating guns from those deemed a threat to themselves or others.

While reasonable people can debate about the best solutions, it is pretty much indisputable that the bipartisan goal of public safety has been a long-running, tragic failure in Philadelphia.

The murder rate in Philadelphia is more than four times greater than in the nation as a whole, according to the FBI’s 2018 stats. The number of shootings and murders in the city has increased since a low in 2013, according to the Philadelphia Research Initiative. Last year, 355 people were murdered in Philadelphia, and in the early days of 2020, the city has been on track to lose even more lives to violence.

“I think the people that are from Philadelphia clearly understand there’s an issue here, that it’s an epidemic that we have to deal with. The legislators that are from the rural parts of the state may not see it as clearly as we do,” says Aleida Garcia, an anti-violence activist whose son was murdered by someone with a gun.

At the meeting convened for gun violence survivors at City Hall, few if any attendees had suffered as much loss wrought by guns as Rosalind Pichardo. In 1994, her ex-boyfriend shot and killed her boyfriend and tried to kill her, she said. Her twin sister was able to buy a gun that she then used to kill herself in 2000. In 2012, Pichardo’s 23-year-old brother was shot and killed during a robbery.

“I don’t believe that the folks in Harrisburg understand what we’re going through,” Pichardo says. Lawmakers from other parts of the state haven’t been through that type of loss, and many are beholden to powerful groups like the National Rifle Association, Pichardo says.

It isn’t easy for Pichardo to discuss the loved ones she has lost, but she speaks up to try to let people know about the awful toll of gun violence.

“It needs to be talked about,” she says.

Photo courtesy Jared Piper / Philadelphia City Council