“A child cannot be taught by anyone who despises him, and a child cannot afford to be fooled.” — James Baldwin

Walking into Njemele Tamala Anderson’s classroom, Bill Withers’ Lovely Day, playing from a speaker, you just might think you’ve entered a graduate level seminar at Penn.

Here, students are connecting the text of Bettina Love’s We Want To Do More: Abolitionist Teaching and the Pursuit of Educational Freedom with their own lives and the world around them. They speak — unselfconsciously, and into one of two handheld microphones they pass around the room — of the importance of representation in literature, of the challenges of being a student of color in predominantly white environments, of attempts by others to make them feel less-than.

But this is no Ivy League course. Rather, it’s Anderson’s 10th grade English class at Science Leadership Academy @ Beeber in Wynnefield. And it’s a model for the ways in which having high standards for our young people — and supporting them with compassion, humanity, and dignity — empowers students to develop confidence, achieve beyond even their own expectations, and be prepared for the world outside the classroom.

“If you touch the humanity of a person, now you’re in a relationship.” — Njemele Tamala Anderson

“Njemele reminds me of the quintessential teachers I used to have — dedicated, motivating, loving and caring, with a high bar,” says Sharif El-Mekki, founder of the Center for Black Educator Development. “The expectations she communicates speak to her belief in our children, in our communities. Her students will work hard for her because of how she sees, hears, and loves them. She remains consistent in her messaging: We are going to do this. Together. In community with one another.”

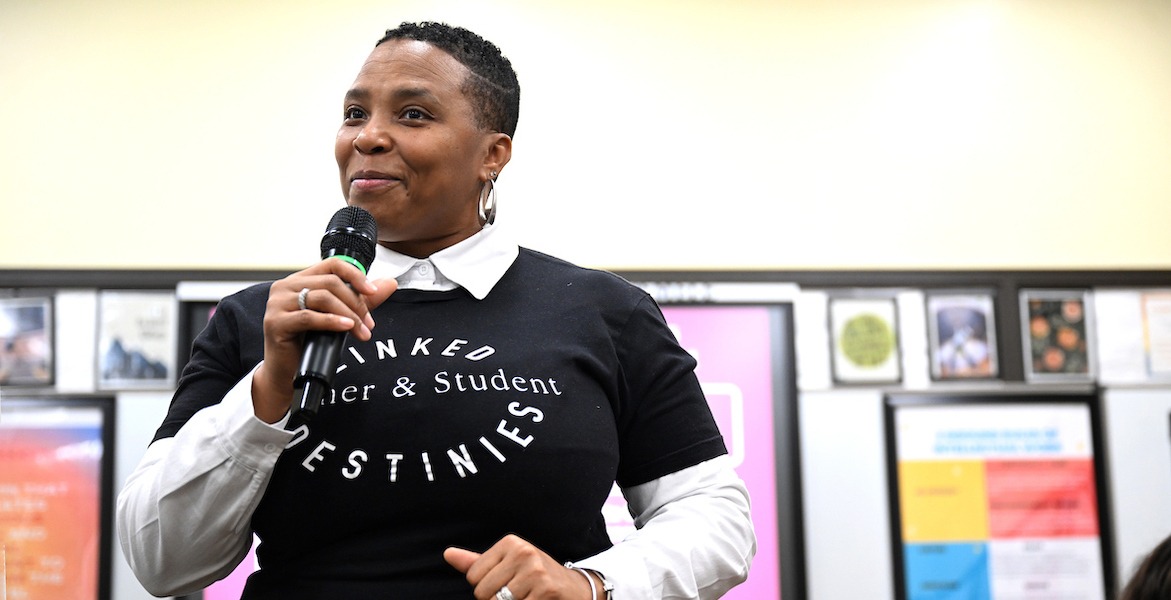

Though it shouldn’t be, Anderson’s is a revolutionary approach to teaching in public schools in Philadelphia. And it underlies why The Citizen is proud to name her this year’s Educator of the Year. For her tireless commitment to uplifting our city’s young people, Anderson will be honored alongside her fellow Citizen of the Year Award-winners at a celebratory dinner on Tuesday, February 25 at Fitler Club Ballroom. (You can read about all of this year’s winners here, and find out about tickets and sponsorships for the star-studded event here.)

Strong roots

Ask Anderson about her journey to becoming an educator, and she will credit three women: Thelma Scott, her great grandmother; Evelyn Solomon, “granny’” and Sharon Layne, her mother. “They would rip my homework out of my book if there was one mistake and have me do it over,” she says. “They had this attention to detail, making sure that I knew how important education was — because they knew it was a vehicle,” Anderson says.

To her foremothers, education didn’t just live in the classroom. Social education was just as important. When The Gallery (now the beleaguered “Fashion District”) was being constructed without employing any Black workers, Anderson’s mother and grandmother protested. When Girard College was not allowing Black students in its ranks, her grandmother was marching around the walls of its campus demanding change.

“Those two things — education and social justice — were constantly fed to me,” Anderson says.

And yet, as Anderson thrived academically in Philly public schools, she never once felt cared for by her teachers. “I did not feel that I had any teachers who liked me. Or who cared about me, the human. I don’t even remember teachers acknowledging my existence with a hello, a good morning,” she says.

“Her students will work hard for her because of how she sees, hears, and loves them.” — Sharif El-Mekki, Center for Black Educator Development

She sensed that same toxicity a generation later when, as a student at Temple, she would spend time volunteering in her firstborn daughter’s classroom. Nevermind that her daughter was academically gifted — she would go on to graduate high school at 16 and earn a full ride to college (more on that, later); Anderson saw that so many of her daughter’s teachers didn’t love kids, didn’t love Black and Brown kids, especially, didn’t see kids as people.

She vowed to be different. To teach differently. To practice Liberatory Education, which is defined on a framed poster in Anderson’s classroom as: “Education that facilitates conscious raising and social engagement to transform the societal structures that do not recognize our humanity.” More specifically, her focus is on the three ground rules of intellectual work, as put forth by Howard University professor Dr. Greg Carr: being present; reading and writing with rigor; and “speaking to mekhet” — that is, contributing to something of lasting worth for future generations.

She cultivated these values over her lifetime, and honed her teaching skills through 20-plus years of teaching in schools — William Penn High School, Mastery Charter Shoemaker, Imhotep Institute Charter High School, Strawberry Mansion High School, Freedom Schools. Imhotep Founder Momma Christine Thomas Wiggins, she says, along with Freedom Schools, have been the biggest influences on her teaching practice outside of her family.

At Beeber, she’s famed for many things. The music she plays in between classes, drawn from a playlist she compiles after asking her students their favorite songs at the start of the year. Her generosity of compliments and warmth; every student gets a “Good morning, baby!” or a “How’re you doing, beautiful?”

Then there are the projects she assigns, tasks that seem absolutely monumental, totally intimidating at the start of the school year, before Anderson has worked her confidence-boosting magic. Last year, she taught an interdisciplinary unit on poetry and social justice through the lens of Hip-Hop, challenging her students to devise raps about a social justice movement of their choosing — and then put together a concert for the community.

“Learning has to be shared into the community — because that gives children a voice and empowers them to know that they’re able to engage in conversations about things that they feel affect them.” — Njemele Tamala Anderson

“One of the things I tell teachers all the time during teacher trainings is that teachers cannot, should not, and need to stop having learning be limited to the four walls of their classroom. Learning has to be shared into the community — because that gives children a voice and empowers them to know that they’re able to engage in conversations about things that they feel affect them,” she says. “After they’ve done critical study and analysis and have come up with suggestions and plans, they need to have an audience in front of decision makers.”

This fall, students had to design their dream schools, using what they learned about educational philosophies like perennialism, essentialism, and reconstructivism; they then had to present their ideas to a panel of experts from around the city including a school CEO, the Deputy Director of Curriculum Instruction for the School District, their parents and members of the community.

“As teachers, we have to create these experiences for young people so that they’re able to have that in their tool belt of experience,” Anderson says.

Anderson hopes to never leave the classroom, as so many other talented teachers are asked to do, to serve in an administrative role. But she does have a big dream: to open her own school, right in the Wynnefield community that raised her and where she still lives.

The Linked Destinies Academy, as she envisions it, will be a high school. It will be private, so that she can avoid the inherent confines and purse strings of public school districts. Everyone will teach, from the deans to the custodial staff. Tuition will be on a sliding scale, so that anyone can afford it. And it will serve multiple generations in the community — grandparents who are raising their grandkids can come and learn how to use SnapChat or Instagram or Google Classroom. Most importantly, everyone who comes out of the school will come out with two things: a skill that will render them employable upon graduation, and a vision and plans for how they will engage in the democracy in which they live.

Changing the culture

On the same December morning when her students are dissecting We Want To Do More, one student takes the mic and asks Anderson a question. “Do you consider yourself an abolitionist teacher? And what are the challenges of being one?”

Anderson takes a deep breath. She looks out at the sea of nearly 40 faces — all but a few students of color.

“Let me put it like this,” she starts. “When you’ve been doing something for a really, really, really long time, you get into the habit of operating a certain way. And so then when you have someone come along and say Hey, you really should think about changing what you do every day because it’s harmful to other people. And that person’s like, Well I’m just breathing. You want me to stop breathing? Is that what you’re saying! That I should stop breathing because it’s making someone else uncomfortable?! That’s what it’s like with racism.”

“Good teachers understand their own biases, understand their own junk. They have to unearth and address and confront what’s going on inside of them.” — Njemele Tamala Anderson

She pauses.

There are teachers, she says, who don’t realize that what they’re doing is really harmful. That there are students who may pass their class, sure, but who have not had a piece of literature, a piece of anything, that connects with their real life experience. That they are being taught as though they are actors in someone else’s story, that they never get to be the star.

“Good teachers understand their own biases, understand their own junk. They have to unearth and address and confront what’s going on inside of them. And not just with racism. With all the isms: sexism, ageism, homophobia. All of them,” she says, being sure to look each student in the eye. “In order to properly address issues of racism in this country, we have to look at all the layers of people, all of the identities of people and take all of these things into consideration when we’re making decisions that affect people’s lives.”

She believes, as her future dream school implies, that the best teachers recognize that our destinies are linked. And she doesn’t just coach current teachers, through professional development training, with this framing — she’s inspiring the next generation of teachers to embrace it, too. Alden Page is in 11th grade. As a student entering Anderson’s class last year, he thought he’d pursue engineering. But Anderson recognized a spark in him — his curiosity, his passion, his personable affect. He’s now part of the teacher training pipeline program, assistant-teaching in Anderson’s class as part of his CTE (career technical education) coursework.

“Ms. Anderson inspired me to become a teacher. I didn’t know about education at all before her class. I didn’t put too much thought into it. But her focus on critical thinking really allowed me to see what I can do in the future, how I can change the future. It made me feel special,” he says. “Liberatory Education allows students to think freely and not be confined inside of a box. We learn about who we are, what we can be, and how we can do it. Her curriculum exposes children to the truth, and the truth is what we need to help lead society.”

Anderson’s oldest daughter, Ansharaye Hines, in a full-circle moment, now works for El-Mekki, doing curriculum development for the teacher training pipeline program, the same one Page and more than 100 students around the district are enrolled in this year alone. “It’s based on her lived experience!” Anderson says with pride.

If it was three women who first set Anderson on her path as an educator, it’s three other women who’ve kept her focused on it: Hines, and her two other daughters, LaShara Jackson and Kijani Anderson. (She’s quick to shout out her husband, Mark Anderson, too.) They may be Anderson’s only daughters by birth, but Anderson has legions of “her kids” around the city who keep in touch with her years after they’ve left her classroom.

“If you touch the humanity of a person, now you’re in a relationship,” Anderson says. “And that’s what it is for me. That’s it.”

![]() MORE PHILLY TEACHER STORIES

MORE PHILLY TEACHER STORIES