It’s been over a year since City Council last had a hearing on Council member Derek Green’s campaign finance reform package, which would have established a new public financing option for local elections, and moved from annual contribution limits to cycle limits—two changes that would be expected to make our elections more competitive. Some good news out of Seattle about the success of their democracy vouchers program in the recent municipal elections could help renew interest in this idea in the next Council session.

Prefer the audio version of this story? Listen to this article in CitizenCast below:

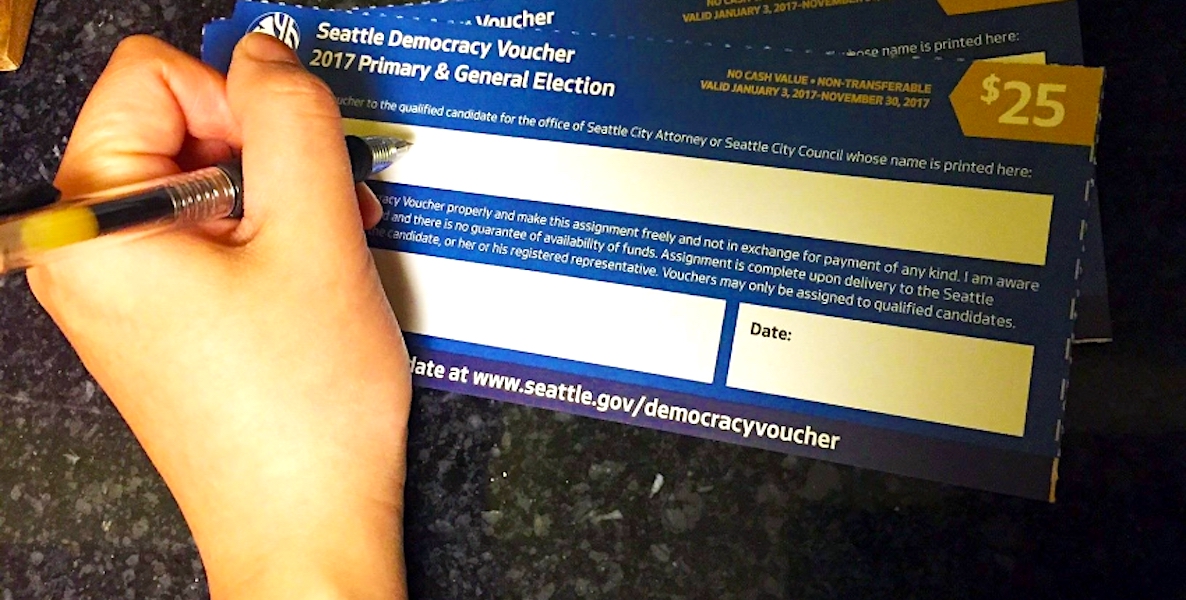

Seattle’s version of public financing—which The Citizen first wrote about in 2017—is interesting in that, rather than guarantee an equal amount of public funding to every candidate who qualifies, the program gives each voter four $25 vouchers to dedicate to the candidate of their choice. To be eligible for public funding, candidates have to collect 400 contributions of $10 or more.

Candidates who opt into the program have to commit to spending no more than $75,000 in the primary and another $75,000 in the general election. If their opponent or an independent entity spends more than $75,000 they can get out from under the cap.

The rationale for the program is to broaden the donor pool for local candidates, increase voter participation in municipal elections, and get candidates to spend more time talking to voters. Having the ability to raise a certain amount of funding from outside the typical network of party gatekeepers is also expected to help broaden the range of perspectives in the candidate pool, and there’s some evidence of that in Seattle’s City Council elections this year.

Gregory Scruggs at Next City spoke with Margaret Morales of the Sightline Institute, a think tank that helped devise the program, who says it’s already exceeded their expectations.

The voucher program has another goal, besides getting more diverse candidates into the field: Get candidates talking to more voters. “We wanted to get more people involved in the political conversation because all of a sudden everyone is a $100 donor,” Morales says.

This is the second election in which the vouchers have been used and records show 3 percent of vouchers have been donated before the primary, a tripling of the 1 percent from 2017 and on pace to potentially match the nearly 6 percent of eligible voters who donate to campaigns in Vermont, the highest rate in the nation.

“The success of the program has blown everybody’s expectations out of the water and we are hitting every single benchmark, including getting a greater diversity of Seattle residents to donate,” says Morales.

There is also anecdotal evidence of success on that front. Ami Nguyen, a former public defender and the daughter of Vietnamese refugees, has been canvassing senior housing in Little Saigon to encourage elderly residents, many of whom have never donated to a campaign or even met a candidate, to pledge their democracy vouchers to her campaign, which has redeemed more vouchers than any other candidate in her district.”

The idea that this could turn canvassing and public appearances into a fundraising activity has some real appeal, since one of the main criticisms of the current campaign finance system is how much it pushes candidates to spend their time doing call-time talking to donors, rather than talking to voters at the door. This gives politicians some added incentive to spend time talking to voters, and ultimately to earn their vouchers.

![]()

This kind of change could also empower membership organizations like unions or other advocacy groups in the election process if they’re successful at coordinating their members to donate their voucher dollars to endorsed candidates.

The early results out of Seattle’s City Council elections look like a mixed-bag, and with votes yet to be counted, we won’t know for a while how candidates who took the democracy vouchers campaign track fared compared to candidates who didn’t, or which kinds of candidates voucher users tended to like.

If the emphasis stays on increasing public participation in the election process, rather than taxpayers doing some kind of favor for politicians, this could become a popular way to involve more people in our typically low-turnout local elections.

Another issue to watch is who participates in the program on the voter side. A Brennan Center analysis of Seattle’s 2017 election found that while the voucher program succeeded in substantially broadening the donor base, donation patterns still roughly mirrored the voter population, which tends to skew older, whiter, wealthier, and more highly-educated. It will be interesting to see whether that pattern holds in 2019 as more voters become accustomed to the program, or if it were implemented here, whether the same pattern would hold in a city like Philadelphia with a much more diverse base of super-voters.

![]()

Politically, the democracy vouchers seem like a more popular idea than guaranteeing a certain level of funding to campaigns, which has been unflatteringly described as the city “paying for candidates’ campaign costs.” If the emphasis stays on increasing public participation in the election process, rather than taxpayers doing some kind of favor for politicians, it could become a popular way to involve more people in our typically low-turnout local elections.

Jon Geeting is the director of engagement at Philadelphia 3.0, a political action committee that supports efforts to reform and modernize City Hall. This is part of a series of articles running in both The Citizen and 3.0’s blog.

Photo via Democracy Voucher Program / Facebook