Dr. Nicole Lipkin knows how lucky she was to have such great parents. Both were teachers in the South Bronx in the 1970s. Unusual for their time, they prioritized creating spaces where their students could talk about their emotions — whether it was concerns over bullying, problems at home or just the general stresses of growing up.

Lipkin’s mom and dad brought the same energy to raising her and her brother, fostering open conversations, one-on-one, as a family, and even inclusive of friends. There was nothing she couldn’t talk about with her parents.

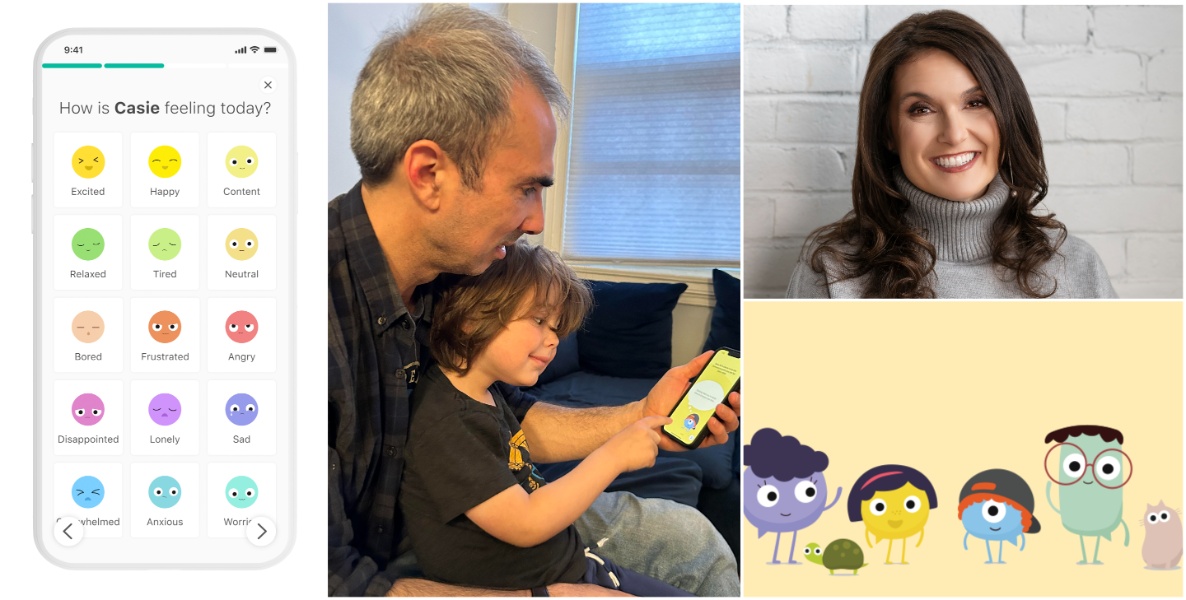

Today, Lipkin, a clinical and organizational psychologist, has made it her life’s mission to foster the same kind of healthy discussions and care both at home and in the classroom, through the HeyKiddo app and educational curriculum. More than 500 families currently use the technology to help children develop their social/emotional intelligence, abilities and resilience.

Although Lipkin’s mom and dad are no longer around to see their daughter’s success — her father died when she was 12; her mother, when she was 19 — she considers her work a tribute to their parenting.

“There is no doubt my life could have gone down a really bad path,” she says. “I have a great life and it’s 1,000 percent because of the foundation” they gave her.

Launching HeyKiddo

Lipkin has been working on the idea that would become HeyKiddo since 2017, starting with an idea for a subscription-based box set that would guide parents and children through a series of activities aimed at helping young people develop social and emotional health, to understand and manage their emotions, develop empathy, make responsible decisions and maintain healthy relationships.

She called it the Young Leaders Project. One activity idea called “stress monster” asked children to draw a picture to represent their stress and then use that stress monster as a vehicle to discuss those emotions in the future. A different, digital version of that activity has made it into the app. The Young Leaders Project won a $233,133 grant from the National Science Foundation in 2018, but Lipkin says she decided to pivot when test users said, “it felt like homework.”

So, she and her team turned to something decidedly not homework-like: a video game. The plan was for it to use similar tactics as the box set to teach children social and emotional health skills in a way that was fun and engaging.

“It’s allowed me to be more patient with my daughter,” Yates says. “It’s helped her be more aware of her emotions, which I think is like such a great gift to give a young child.”

The early concept showed promise, but they decided to focus solely on the dashboard for funding reasons. They added a feature that would send guidance via text to parents on how to talk to kids about current events, like political violence or climate anxiety. The texts could make parents feel guilty, however.

The messages themselves were innocuous — they merely suggested parents start a conversation and offered resources if something happened that could make a child anxious — but they could arrive at less than ideal times. Parents might be working or away from their children and couldn’t always facilitate a conversation immediately and would worry about when they would have time. The system lacked a tool parents and kids could engage with on their own schedules.

“As a parent, they’re just guilted left and right,” Lipkin says. “We knew that we had to evolve this into something that wouldn’t cause guilt.”

Then the pandemic hit. As schools went virtual, elementary-age kids experienced new mental health challenges, including questions about the virus that were hard to process. Many worried their parents would die if they became sick. Beyond that, Covid exacerbated existing mental health challenges kids were facing.

In 2020, during the first year of the pandemic, mental health-related emergency room visits for kids ages five to 11 rose 24 percent. “There wasn’t one person … that knew what was going to happen. None of us knew. It was a constant change,” Lipkin says. “We all went online and started looking at ourselves on camera. You saw a spike in adults getting plastic surgery and developing self-image issues. Well, among young kids, it was the same thing — a huge spike.”

Lipkin and her team started work on an app that combined some of the features of the video game — the dashboard, the resources for facilitating tough conversations — but instead of texting that information to parents randomly, it featured a library where parents could access the resources on their own time.

Lipkin won a $275,861 National Science Foundation grant in 2021 to support phase one of the research and development process, using her core team of psychologists, app developers, and researchers to build the product.

Then, in 2022, while attending the Philadelphia Alliance for Capital and Technology Capital Conference, Lipkin pitched a quintet of local venture capitalists during a Shark Tank-style event. She raised $400,000 from John Martinson, chairman of Martinson Ventures, and Ira Lubert, co-founder of Independence Capital Partners and partner of LLR Partners.

Starting conversations

HeyKiddo has two primary options: There’s an app for parents, and there’s Huddle, a tool for educators. At first, Lipkin was uncertain about creating something for teachers — she knows they have so much on their plates already — but she believes building children’s mental health requires collaboration. Her parents, after all, were doing this both at home and in their jobs as teachers.

Both parts of the app focus on children between the ages of five and 12 because, she says, “Why don’t we tackle this one during this elementary school age when brains are just so ripe for it? We can build that foundation.”

The app allows parents to build a goal-centered profile for their child. One parent might want to work on improving their child’s self-esteem; another might want to help their child decrease angry outbursts. The app takes these goals and offers parents targeted feedback. The user interface uses bright yellows and greens and cute cartoon animals to make the system feel uplifting and friendly.

Once a profile is created, parents can begin logging their child’s mood and recording issues. The app offers prompts that can help facilitate conversations, or it can recommend activities that parents and children can do together to soothe anxieties or calm them down after an outburst. (It also has a chatbot, although company is also in the process of incorporating AI elements to it.)

A mood-tracking dashboard lets parents spot red flags. If parents have specific concerns, they can explore a research library of articles written and vetted by the HeyKiddo team that offer advice on a wide range of mental health topics. “It’s all evidence-based. It’s tried and true,” Lipkin says.

Emily Yates, SEPTA’s chief innovation officer and the mother of a five-year-old son and nine-year-old daughter, started using HeyKiddo as one of the first research users after meeting Lipkin through their children — their sons are the same age.

As we chat, she walks me through how the app might help her manage her daughter’s academic anxiety. It starts by having Yates record her own feelings before asking about her child’s emotions — a feature that allows her to stop and consider whether her own moods are affecting how she engages with her children.

Then it suggests a few activities they could do together that could help her daughter slow down and process her anxiety, offering some prompting questions for parents to initiate conversation.

Yates says she appreciates that the app quickly provides guidance and then directs her back into engaging with her children IRL. “It’s helping me better understand where these sudden emotions are coming from. I’m more equipped to handle them,” she says. “I’m not going to diminish her situation where she’s feeling big emotions. I’m going to understand what’s underlying whatever it is, and work with her on that.”

The app allows parents to build a goal-centered profile for their child. One parent might want to work on improving their child’s self-esteem; another might want to help their child decrease angry outbursts. The app takes these goals and offers parents targeted feedback.

Helping in the classroom

HeyKiddo’s other tool, Huddle, is designed as an education curriculum for elementary school educators to help facilitate social and emotional learning in the classroom. Huddle offers flexible conversation starters around mental health and children’s emotions.

Depending on what they feel is best for their classroom, some educators might use the tool multiple times per week, while others a few times a month. It also offers creative activities developed by art therapists and tools for talking about difficult topics, like school violence or bullying. Parents get an email each week detailing what their children have learned.

“We’ve tried to make it as simple as possible so you don’t need to be trained to deliver it,” Lipkin says. “This should not be the stressful part for educators.”

Springfield Township School District in New Jersey started using Huddle as a pilot just as the pandemic was waning. Homeroom teachers use it to facilitate conversations with first through sixth graders. When they started, “it was like pulling teeth to get these kids to talk,” says Craig Vaughn, superintendent and principal for Springfield Township School District. Now, kids eagerly participate and carry the conversations themselves.

Vaughn says it helped improve peer-to-peer relationships, especially among older kids. “One of the coolest things was the awareness that it created among students,” Vaughn says. “We saw our fifth and sixth graders getting into a position where they were comfortable opening up in front of their peers.”

Lipkin is clear that these tools aren’t meant to replace professional psychologists. The app’s mood-tracking dashboard can help parents determine if their child might benefit from professional support. The app is also not meant to keep families looking at screens, which can take a toll on mental health. After a minute or two, the app encourages parents to facilitate in-person conversations with their children.

“With both the app and Huddle our goal is to get people off of technology talking to each other,” Lipkin says.

Over 500 families are currently using HeyKiddo. It costs $14.99 per month or $119.99 yearly for non-research users. The Huddle offering is newer and in only a handful of schools, many out in California, and Lipkin did not confirm the exact number.

HeyKiddo’s future

Though the HeyKiddo app is available for parents to download in both Apple and Google app stores, Lipkin still considers the business very much in the research and development stage. She hopes to find a way to combine the work of the app and Huddle so that parents and educators can work together. (People interested in becoming research users, should sign up for email updates on the app’s site.)

Her team has worked hard to make sure their content is both wide-ranging and culturally-sensitive, though she’s also hoping to create offerings targeted toward families who might face unique stressors, like military or foster families.

“I’m leading with the clinical because this is people’s mental health,” Lipkin says. “This is people’s lives. I believe in doing this right, versus doing this quickly.”

Yates believes the app has taught her and her daughter better ways to manage emotions. It’s helped facilitate conversations about academic anxiety, friendship dynamics and other social and emotional health topics with her children.

“It’s allowed me to be more patient with my daughter,” Yates says. “It’s helped her be more aware of her emotions, which I think is like such a great gift to give a young child.”

Corrections: A previous version of this post had a different timeline for the app’s development. Lipkin’s core team has been together since The Young Leaders Project. The app’s chatbot is now functional.

![]() MORE ON YOUTH MENTAL HEALTH

MORE ON YOUTH MENTAL HEALTH