He’s not straight from central casting, that’s for sure. A few weeks ago, moving his office from Capitol Hill’s Cannon to Longworth buildings, the cherubic 39-year-old Congressman Brendan Boyle found himself dealing with someone with the title of “Congressional Move Coordinator” who assumed she was talking to the Congressman’s staffer.

“How is the Congressman to work for?”

“Oh, he’s terrific,” Boyle replied, playing along. “He really cares. He’s a great boss and a great guy.”

It was just the latest in a string of examples that have seen Brendan Boyle defying expectations. That’s what he did when he first got elected to represent the Far Northeast in the State House in 2008, running a grassroots campaign without Democratic party support. (His brother, Kevin Boyle, did likewise, defeating former Speaker of the House John Perzel in 2010). That’s what he did in the Congressional election of 2014, when, despite the fact that Ed Rendell and the Clintons were for Clinton in-law and former congresswoman Marjorie Margolies, Boyle toppled the establishment in a race that presaged many of the themes that would animate the 2016 presidential election, including income inequality and a rejection among white working class voters of politics as usual.

And that’s what he’s trying to do in Congress, where he’s about to take on the mother of all legislative challenges: Reforming our broken political system. Last month, Boyle closed out his first two-year term (he was reelected in November with no opposition) having filed The Clean Money Act, a bill that would rethink the way we fund elections.

“We need Trump voters demanding change, as well as populist conservatives and progressives,” says Brendan Boyle. “That’s the marriage that gets this done. And if we can change the way we get elected, we can change a whole lot.”

The genesis of the bill came in the spring, when it dawned on Boyle that he was hearing the same thing from Sanders and Trump supporters. “I heard time and again in my district, people who were voting for Trump saying, ‘Yeah, but at least I know he’s not bought and paid for,’” Boyle told me over a recent Center City lunch. “Trump and Sanders supporters both strongly felt that all of us, this whole system, is corrupt.”

So he took to the floor of Congress to speak out in favor of one of the campaign finance bills winding its way through the system.

But as time went on, Boyle returned to his wonky public policy chops, honed at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, and began devising his own bill, The Clean Money Act. “My whole theory, and I believed this even before I started knocking on doors and running for office, is that ever since the first campaign finance reforms passed after Watergate, we’ve had all these efforts to limit the supply of money in politics and yet almost no effort to go after the demand,” he says. “In other words, why do we need all this money? The good news is that, unlike in previous eras, it’s not like elected officials are keeping the money they raise. Eighty percent of it is going to pay for TV ads and a high percentage of the remainder goes to direct mail. So instead of continually coming up with contribution limits, which will always be gotten around because of the First Amendment—the Citizens United ruling makes limits essentially meaningless—why don’t we just go after the demand side?”

Boyle’s plan would do that through a publicly-financed system that would provide campaigns with tax credit vouchers they can redeem with TV stations. Rather than pay cash for air time, candidates could use a voucher, provided by the federal government, which would remove the cost of TV advertising from their campaign. “It’s an opt-in system, you can’t force candidates to accept public financing,” Boyle says. “But most candidates would opt in. Someone like me? You mean I wouldn’t have to fundraise anymore and I would basically be able to get my message out? And I’ll be able to brag that I’m in the clean money system? It’s a no-brainer. I’m not naive. This won’t solve 100 percent of the problem, but it will help solve the vast majority of it.”

Of course, one of those post-Watergate reforms was public financing of presidential elections; taxpayers could check a contribution box on their tax returns, and, from 1976 until 2004, that money financed the election. But that system didn’t keep pace with inflation or the explosion in advertising and political consultant costs. Candidate Obama was the first to opt out of public financing in 2008, and now nobody is in it. Boyle points to the 1984 campaign—when Ronald Reagan held all of 8 fundraisers, compared to Obama’s 300 in 2012—as proof that public financing worked for many years.

His reform, however, would do away with the tax return check box tradition. “I think it should be part of the federal budget,” he says. “We’re talking about 0.001 percent of the discretionary part of the budget. I want to send the message this is important. It’s about the integrity of our democracy and it should be paid for with guaranteed public funds. We pay for the voting machines, we pay for the people who work the polls, we pay for the ballots. Well, why don’t we pay for the biggest cost of modern campaigns, the cost of getting your message out?”

There are other similar bills floating around Congress, like Maryland Democratic Rep. John Sarbanes’ Government By The People Act and North Carolina Democratic Rep. David Price’s We The People Act , and Boyle is a co-sponsor of both. But his bill is the first to so exclusively focus on the demand side of the campaign reform equation. He’ll be reintroducing it in the coming weeks and anticipates roughly 20 co-sponsors. “I’m reaching out to the newer members who were just elected as part of the Trump wave to see if this is something they can champion,” he says. “It’s a very anti-establishment bill.”

Get More From Every Story

We include boxes in nearly every story to help you take action. Click the boxes below to see how you can make Philly better.

Generally, a congressman in the minority party who is just starting his second term in an institution based on seniority wouldn’t stand much of a chance of shepherding such an ambitious idea into law. But Boyle is right that there is something of an opening here. Donald Trump got elected, in part, thanks to his promise to “drain the swamp.” Judging by his appointments—nary a populist among them—he’ll need to show his voters he’s doing just that.

Who would oppose campaign finance reform that attacks the demand side? Well, given that broadcast and cable networks make out like bandits during campaign season, it’s likely they’d lobby against any deviation from the current system. And what about Boyle’s colleagues in Congress? “The vast majority of them hate call time and bitch about the current system,” Boyle says. “Yet there is an inertia about changing the system because a lot of people are afraid that under a new system they’d be empowering someone to beat them. No one has said that, but that’s my logical deduction.”

Which gets us to the nexus of campaign finance and congressional reform. Last April, Boyle was watching as 60 Minutes aired a report about Republican Congressman David Jolly, who says that, the day after he was elected, his party’s leadership told him his job was to raise $18,000 a day on the phone in secretive congressional call banks. For congressmen like Jolly, who, unlike Boyle, found himself representing a district that would always be electorally in play, it is expected that they spend four hours a day dialing for dollars. Jolly proposed The Stop Act, a bill that would prohibit members of Congress from asking for money—period. Their staffers still could, but at least our elected representatives could spend their time legislating. Of course, Jolly only got six co-sponsors, the bill went nowhere, his party felt betrayed and didn’t help in his reelection bid, and—lo and behold—Jolly was voted out of office in November. Now Boyle plans on reintroducing Jolly’s bill in the coming weeks.

“You mean I wouldn’t have to fundraise anymore and I would basically be able to get my message out? And I’ll be able to brag that I’m in the clean money system? It’s a no-brainer,” Boyle says.

“I didn’t know about The Stop Act until I saw 60 Minutes and I want to make sure that, now that he’s left Congress, the bill doesn’t die,” Boyle says. “It’s a really interesting idea. Understandably, we always look at whether a politician is conflicted because he received $2,500 from X and then votes the way X wants. But no one stops and says, ‘Wait a minute. We’re paying 435 people to legislate, does it really make sense to have them all in a call room spending a high percentage of their time not studying policy but being a telemarketer?’ That’s why I really like Jolly’s approach.”

Despite Boyle’s Harvard pedigree, he’s no cultural elitist, and his party would be smart to divine some policy prescriptions not just from his thinking on money and politics but also from how he’s put together a diverse coalition around economic justice issues. He grew up in Olney, the son of Irish immigrants. His father was a SEPTA maintenance worker and his mother a crossing guard. For a good part of Boyle’s upbringing, Olney was racially mixed. By the time he ran for Congress, his old neighborhood was almost entirely African-American. He knocked on every door of his district, and his best performance in the hotly contested 2014 primary came in the African-American ward, where he received 81 percent of the vote. “This is especially relevant after November 8,” he says. “People say, if you go after white blue collar voters that means you’re ignoring African-Americans. Well, not at all.”

So if he could advise his party, still reeling from its widespread rejection at the polls, what would he say? “Look, I don’t pretend to have all the answers,” he says. “But one place where you can immediately start is to realize it’s really hard to get people’s votes when you’re condescending to them by saying, ‘We’re really good for you, and you just don’t understand that.’ Look, a guy named Barack Hussein Obama won Pennsylvania twice. It’s not like people who voted for him twice suddenly became KKK members. It’s really unfair, and it’s kind of delusional and self-comforting, for people on the left to say, ‘Oh, it’s just white rednecks who voted against Hillary.’ You’re just saying that to make yourself feel better. So my advice would be to recognize that people can feel if they’re being caricatured by the Hollywood or Manhattan crowd. So I would say, you know, first do no harm.”

And demonstrate that you’re on their side—which “draining the swamp” of politics just might do. Campaign finance reform is an abstract issue; voters don’t feel it viscerally. But, for the first time, Boyle thinks voters are seeing the way we fund campaigns as directly linked to an insider system that has had its way for far too long. Our lunch concluded, this Congressman who looks like an intern and who has merged an interesting coalition of disparate groups into a governing majority says that that’s what it will take now, on a much broader scale.

“We need Trump voters demanding change, as well as populist conservatives and progressives,” says Brendan Boyle. “That’s the marriage that gets this done. And if we can change the way we get elected, we can change a whole lot.”

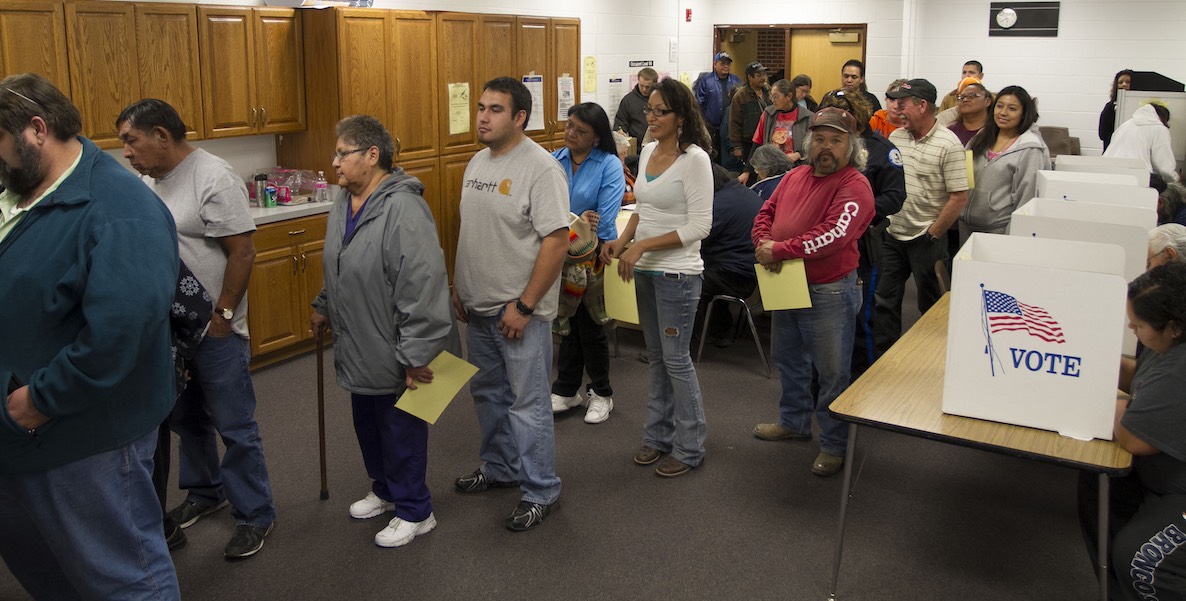

Header photo: Congressman Boyle Boyle questions FBI Director James Comey in Oversight hearing in July 2016