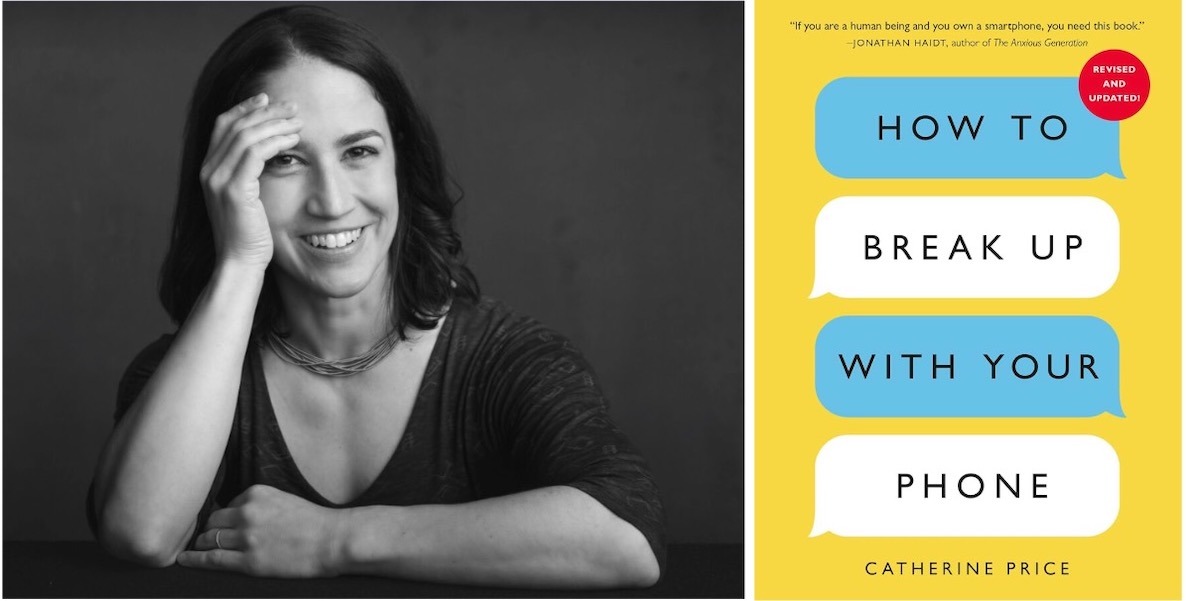

This past Valentine’s Day, Philly-based health and science journalist Catherine Price appeared on CBS This Morning to discuss her research and the release of the revised and updated edition of her book, How to Break Up With Your Phone. The segment hosts introduced Price and her book with an obvious nod to Valentine’s Day, referring to our phones as the “third wheel” intruding into our relationships, and calling our relationships with our phones a “bad romance” and borderline “abusive.”

It was your typical light morning show banter, designed for obligatory chuckles. But it also captured how the relationship metaphor that Price uses to frame the book is so instantly recognizable to all of us, and a testament to Price’s ability to illuminate what until recently has been hiding in plain sight: our daily, unexamined intimacy with the technology that shapes us in ways we fail to consciously acknowledge.

Price has spent close to a decade studying the effects of constant smartphone use. She started working on the first edition of How to Break Up With Your Phone in 2016, at a time when, in her words, “most people were not thinking about the potential dark sides of our device use.” In fact, initially Price and her agent struggled to find a publisher interested in the book, eventually going with Ten Speed Press, who had just published Marie Kondo’s wildly influential, The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up. (Coincidentally, The New York Times tech journalist, Kevin Roose dubbed Price “the Marie Kondo of brains” back in 2019.)

The book came out in 2018, and Price describes it as “a slow burn of a book,” mainly spreading by word of mouth. In the fall of 2023, Price realized that an update was necessary, and a revised version came out in February.

Of course, a lot has changed over the last six years. For one thing, more and more of us have woken up to our device dependency. And back then, Price was admittedly “making a lot of educated guesses about stuff,” including hypotheses about how our use of smartphones might be affecting our brains. In the time that’s passed, we now have things like The Wall Street Journal series The Facebook Files, and documentation from TikTok executives that have proven just how clearly these companies are acting in bad faith.

In addition, much of the research on the effects of these technologies was just starting out. Now we have much clearer evidence of the negative impacts, most notably, the work of social psychologist and author, Jonathan Haidt’s bestselling book, The Anxious Generation, which has been labeled as “the generation-defining investigation into the collapse of youth mental health in the era of smartphones, social media and big tech.” Price has since begun collaborating with Haidt and his team to try and better tackle the challenge of what we can do to help kids manage their relationships to their phones.

But one thing that hasn’t changed: People immediately get the relationship metaphor. “When I first said, I’m writing a book about how to break up with your phone, no one was like, I don’t understand what you’re talking about.” Price says. “They might have said, I don’t want to break up with my phone. I love my phone. But it’s not about dumping your phone. It’s about a healthier relationship.”

The Seinfeld of science writers

Price grew up in New York City, surrounded by friends’ parents who were mostly a part of the professional class — lawyers, doctors, financial professionals — and though she always liked to write, she didn’t really know how to go about making it a career. After college at Yale, she set out to write essays in the style of David Sedaris, but to pay the bills, she briefly taught ice skating at Wollman Rink in Central Park, which led to becoming a substitute Latin teacher at an all boys school, and later a math teacher.

Eventually, Price ended up in journalism school at University of California, Berkeley, where one of her mentors was the journalist Michael Pollan, who had just published The Omnivore’s Dilemma and was nurturing a whole generation of food writers. Price had been diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes as a senior in college, which forced her to learn about biochemistry and the impact of our environments on our bodies. She realized “that science is not, in fact, boring. It’s actually fascinating, especially when it comes to how our bodies work, specifically in that process of learning for yourself.”

“It’s not about dumping your phone. It’s about a healthier relationship.” — Catherine Price

Price began writing about a range of topics related to food, nutrition, health and science. She wrote a cookbook that came from a connection to Eric Schlosser, of Fast Food Nation fame, and eventually launched a Substack newsletter, How to Feel Alive with Catherine Price, which often generates notes from readers thanking her for “changing my life.”

You can think of Catherine Price as the Seinfeld of science writers — she pulls profound insights out of life’s habitual, often mundane patterns while leaving us wondering how we never noticed the everyday absurdity of many of our unconscious behaviors. She’s written about how having fun is critical to our well-being, how vitamins revolutionized the way we think about food, and shared 101 places to not see before you die, demonstrating how the modern proclivity to treat travel like a checklist means we’re “missing the point of leaving home.”

Thankfully, Price goes one step further than Jerry’s punchlines: She follows insights with solutions. Her last two books have included second half step-by-step, evidence-backed plans for helping us put into action what she’s presented in the first parts. And these days, as our conversions about our relationships with technology have become increasingly charged, Price’s voice, and the way she reframes our phone habits as a relationship, rather than a moral failing, offers us a practical way to create the necessary space for honest reflection that we desperately need.

A social litmus test

Last year, as cell phone bans in schools gained increasing national attention, the topic occasionally surfaced among parents at playgrounds and school drop-off lines, serving as an inadvertent social litmus test. It was rarely debated, but concerned parents silently registered the reactions of others: That parent was alarmed by social media but not by smartphones; this parent supported complete restriction; that one believed kids need to become more tech savvy to achieve future success; this one was concerned but resigned, thinking it was too late to change things; many others just deflected with humor. This unintentional social barometer often revealed deeper anxieties about technology, parenting philosophies and the uncharted territory of raising children in a digital world we all struggle to navigate ourselves.

Over the course of last year, eight states banned cell phone use in schools, and an additional 16 issued some sort of legislation aimed at curbing usage.

This came after former Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy called on Congress to require that digital warning labels be applied to social media platforms, as well as the influence of Haidt’s book and ongoing research. Murthy and Haidt pointed to extensive research showing that social media is linked to significant mental health harms in adolescents. And all this came as legislators, educators, and parents were reckoning with the reality that social media use by kids aged 13 to 17 has become nearly universal — up to 95 percent report using a social media platform with one third self-reporting to use it “almost constantly.”

These factors influenced Republican Pennsylvania State Sen. Ryan Aumont to sponsor a bill last year that was aimed at achieving a statewide cell phone ban in schools, and intended to “address a root cause of the mental health and academic decline experienced by PA students.” Ultimately, the bill did not result in a ban, but did provide mental health grant money for schools to purchase secure, lockable, Yondr-like bags, and required participating districts to ban cell phone use during the school day.

Meanwhile, parents remain divided between safety concerns, worrying about not being able to contact their child if something were to happen at school — an all too common occurrence these days — and mental health worries, while administrators hesitate to lead what one parent called “a cultural change to reduce the omnipresence of cell phones and social media in our children’s lives.”

No judgement

In this emotionally charged landscape, where discussions about smartphone use can quickly become twisted into judgmental takes on parenting philosophy, Price offers us something remarkably different: a voice that neither scolds nor alarms, but invites.

Besides Haidt’s work, there was most recently the same-day release of Chris Hayes’ and Nicholas Carr’s new books which argue that “our capacity for attention and connection has been devastated by the digital age.” Fundamentally, both books are warnings, with some prescriptive material. Or consider Dr. Anna Lembke, Stanford addiction specialist and author of Dopamine Nation, whom Price frequently references.

“I wanted to understand the mental, emotional, and physical effects that my phone time was having on me. I wanted to know whether my smartphone could be making me dumb.” — Catherine Price

Recently The New York Times magazine interviewed Lembke, who offered valuable clinical insights about “digital drugs” that “put us in a trancelike state,” but her personal take — she shared that she did not have internet in her home until her daughter reached high school — has the potential to create distance rather than connection.

Price’s approach to informing and guiding us emerged from a deeply personal, relatable moment. Back in 2016, when she was up late with her newborn daughter, she had what she refers to as a “momentary out-of-body experience — probably brought on by sleep deprivation — in which I saw the scene as if I were an outsider: There was a baby, staring up at her mother. And there was her mother, staring down at her phone.”

And thus started her personal investigation into her relationship with her phone, or what she describes as turning her “personal curiosity into a professional project,” one that she embarked on with an honest fallibility that almost all of us can relate to:

I realized that anytime I had to wait for anything — a friend, a doctor, an elevator — my phone magically appeared in my hand. I found myself glancing at my phone in the middle of conversations, conveniently forgetting how annoyed I felt when other people did the same to me. I checked my phone constantly, presumably so that I didn’t miss something important. But when I evaluated what I was doing, ‘important’ was pretty much the last word that came to mind.

As Price writes in the introduction to the book: “I wanted to understand the mental, emotional, and physical effects that my phone time was having on me. I wanted to know whether my smartphone could be making me dumb.”

What to do

Despite the mounting evidence about technology’s impact on youth mental health — and even the clearly rebutted response to pushback on the evidence — many of us resist acknowledging the problem. It can feel both overwhelming in its scope and intensely personal in its implications for how we parent and live our daily lives. So where do we start?

Price’s book is an invaluable resource for how to think, talk about, and act on this problem — for us and for our kids. The 30-day break up section of the book offers up so many helpful hacks and suggestions for making your phone less of a distraction, and for modifying your behavior in simple ways.

What makes Price’s approach particularly effective is how she identifies our common mistake: starting with vague statements like, I should spend less time on my phone without specifying why or what we want instead. As she puts it, this is “the equivalent of dumping someone because you say you want a ‘better relationship’” without knowing what you want that better relationship to be like. By framing our tech use as a relationship that needs boundaries rather than a habit to eliminate, Price helps us “transform our phones from temptations into tools.”

“Instead of asking what our children will miss out on if we don’t get them smartphones and social media, we should be asking what they will miss out on if we do.” — Catherine Price

Her suggestions are refreshingly practical and infused with humor that removes any sense of judgment. Some of her recommendations include:

- Buy an alarm clock before you start the break up (to keep phones out of bedrooms).

- Establish no-phone zones in your home.

- Embrace JOMO (the Joy Of Missing Out) instead of FOMO.

- Create “speed bumps” that can be physical, like wrapping a rubber band or hair tie around your phone that forces you to pause before mindless scrolling, or digital bumps, like “changing the image on your home or lock screen to a question, such as ‘Why did you pick me up?’”

- Use her “WWW” method, asking: “What For, Why Now, and What Else” before checking your phone.

She also recommends writing actual breakup letters to your device, pointing to her own at the beginning of the book and examples from previous break up participants for inspiration. This is, she says, “objectively a playful, silly, even weird thing to do,” but can often end up becoming “quite poignant and vulnerable.”

Take, for example, Price’s letter. At one point, she notes, “At first it seemed strange that you wanted to come with me to the bathroom — but today it’s just another formerly private moment for us to share,” and “Thanks to you, I never need to worry about being alone. Anytime I’m anxious or upset, you offer a game or news story or video to distract me from my feelings.” Throughout, she maintains that “there is no judgment in this breakup” — and reiterates that the goal isn’t deprivation but reclaiming attention for what truly matters.

Price is currently wrapping up a month-long break up challenge through her newsletter, and even without the real-time interaction, the video posts and FAQs present a helpful model for how to implement the 30-day digital detox presented in the book.

Last, Price’s post: Kids, Smartphones, & Social Media, is an invaluable “roundup of resources for parents and caregivers — and an invitation to take collective action to protect our kids.” In this post, Price offers what may be the most sensible logic for how to think about this problem: “What, if any, evidence is there that smartphones and social media have positive effects on youth mental health? And with that in mind, for us to simply consider weighing the risk versus reward of deciding to delay our children’s access to smartphones and social media, compared to the potential harm, if we don’t?” And finally, and most fundamentally, “Instead of asking what our children will miss out on if we don’t get them smartphones and social media, we should be asking what they will miss out on if we do.”

Most teens have come to openly acknowledge their addiction to their phones and social media. They may laugh or shrug it off, as just how things are these days, but underlying that admission, is a fundamental framing for understanding addiction: that its opposite is not sobriety — but human connection. What does it say about us, if we are acknowledging, and our kids are saying to us, what we all know to be true: that we need real connection. Yet we’ve let our devices hijack real connection, and these devices are changing our brains (see chapter 5), increasing our isolation and loneliness (see chapter 4), and negatively affecting our overall happiness and health (see chapter 8).

Price admits she may not have all the answers (although she offers up a lot of them), but she is helping us see the challenge more clearly, and pointing us towards a path of collective action, which not for nothing, is a pretty great way to create real, meaningful connection. You could even start this weekend.

![]() MORE ON TECHNOLOGY AND ITS IMPACT

MORE ON TECHNOLOGY AND ITS IMPACT