When historian Carter G. Woodson established in 1926 what was, at the time, dubbed “Negro History Week,” it wasn’t for the purpose of celebration.

Woodson and others hoped that such a week, which eventually morphed into a full month by 1976, would serve as a full-curriculum way for society not to repeat and continue the nation’s racist inclinations, rather to “take the study of the Negro seriously.”

![]() Indeed, by formalizing black history into a real field of academic study, Woodson thought, black people as a whole would be taken seriously, respected as equals and permitted to exist in the United States and throughout the world unencumbered by white supremacy.

Indeed, by formalizing black history into a real field of academic study, Woodson thought, black people as a whole would be taken seriously, respected as equals and permitted to exist in the United States and throughout the world unencumbered by white supremacy.

“The same educational process which inspires and stimulates the oppressor with the thought that he is everything and has accomplished everything worthwhile, depresses and crushes at the same time the spark of genius in the Negro by making him feel that his race does not amount to much and never will measure up to the standards of other peoples,” wrote Woodson in his classic work The Mis-Education of the Negro.

Through Negro History Week, then Month, then Black History Month, Woodson set out to aggressively reverse and correct that. Specifically set in February because of the converging birthdays of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln, Black History Month was designed as a revolutionary resistance and liberation weapon towards that goal.

Here we are 94 years later, and it’s not clear if that specific mission was successful. There are growing signs that America happily observes or celebrates Black History Month as a matter of course and that’s all fine. Yet, that observance is as dismissive as it is insincere and obligatory.

Most Americans are not even certain if they want a “Black History Month” at all, according to a 2018 YouGov poll, and if it’s just better to “integrate” it into the general curriculum. More significantly, there are signs the larger public has no understanding of key struggles in that history.

Only 29 percent of Americans, according to an Associated Press poll, support the idea of reparations, which was originally designed and offered by the Union as a form of redress to the formerly enslaved. Perhaps that number would be higher if more people had a full understanding of what reparations was for.

“In a dual effort to provide for the newly freed black folks while simultaneously breaking up and redistributing Confederate land and holdings, General Sherman produced what is known as Special Field Orders №15,” notes Dr. G.S. Potter in a 2018 BEnote over concern that the history of reparations was being distorted so other political interests could co-opt it. “This order took a slice of formerly Confederate land that stretched Florida to South Carolina and redistributed it to newly freed black families in 40-acre parcels. Approved by President Abraham Lincoln, Sherman’s Order is where the promise of 40 acres and a mule first originated. This is where the promise of reparations for slavery originated. In the harshest battles of the Civil War. With black people. Black people that risked their lives to secure freedom. During the Civil War.”

The majority of Americans, however, aren’t even all that clear on the history of slavery, as a 2019 Washington Post-SSRS poll shows: Only 36 percent know that the 13th Amendment abolished slavery, and an alarmingly high 41 percent believe it was “another reason”—not slavery—that triggered the Civil War.

Contemporary celebrations of black history have a troubling tendency to confine that history to what’s happened over the past 500 years in North America.

As a Southern Poverty Law Center report explores, the American education system overall isn’t doing the best job teaching these essential facts, which might explain why the general public still ignores or rejects black pain.

“More than half [of teachers] (58 percent) reported that they were dissatisfied with their textbooks, and 39 percent reported that their state offered little or no support for teaching about slavery,” said the report.

While a majority, 58 percent, believe wearing blackface is “unacceptable,” 42 percent say it’s either “acceptable” (16 percent) or they’re “not sure” (26 percent), according to an Economist/YouGov poll.

Indeed, a 2017 poll found that a slim majority of Americans believe “the [Confederate] flag mainly represents Southern pride rather than racism. And by 54 percent to 26 percent—a 28-point margin―the public sees statues of Confederate war leaders such as generals Robert E. Lee and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson as symbols of Southern pride, rather than racism.”

![]() If Black History Month, now relegated to a hashtag, was truly meeting its goals then we’d have greater American clarity on those issues and more.

If Black History Month, now relegated to a hashtag, was truly meeting its goals then we’d have greater American clarity on those issues and more.

We wouldn’t have a University of Michigan bookstore hanging dolls representing famous black historical figures on a “tree rack” as if they were being symbolically lynched. Yet, black students on predominantly white college campuses, not just Michigan, find themselves daily assaulted with the indignities and full-blown hostility of white-lashing bigot porn from blackface (folks are still doing that) to bananas to Klan-jokes to off-base, micro-aggressive comments in classrooms and many more dangerous episodes resulting in outright hate crimes.

In many cases, the animus builds up and gets outright hostile and deadly: such as the tragic murder of Lt. Richard Collins III, a Bowie State University student, by a white supremacist University of Maryland student.

If Black History Month was really working, elementary, middle and high school teachers throughout the nation would understand it’s in bad, miseducating taste to force black students to re-enact slave plantation dynamics. White students, as well, would pause before creating racist social media threads or celebrating Confederate memorabilia.

That type of hostility toward black existence is, of course, not just confined to school yards. A fresh, 21st century revival of globe-trotting white nationalism is being baked into our political process, discourse and policy-making, and in a manner that is unapologetic and much more sophisticated in scope and implementation.

That is, of course, another entire round of columns, but we’re all seeing an escalation of antipathy and violence toward defenseless people in black skin being in the wrong spaces at the wrong time. But, the open terrorizing and disrespect of black agency is becoming a regular feature of the white fragility of some who fear the erosion of long sustained privilege.

All of that, mind you, is being supported by a vicious framework of social and economic barriers designed to keep black people in constant second-class citizen mode—without feeling the beating heat of sun on a cotton field.

Black people still find themselves accosted by the same issues from 50 years ago, and even earlier—a maddening labyrinth of low social mobility, lack of affordable housing, either no-credit or higher interest rates (recently, we find, even just for going to an HBCU), food deserts, over-pollution and disproportionate climate change impacts, to name just several.

In Philadelphia, that has resulted in unequal economic, health and life expectancy outcomes for black people versus white people. The city controller’s office illustrated this just last month, with a map that shows the majority of homicides in the city falling on neighborhoods subjected to racist redlining as far back as 1937.

Nearly 200,000 black Philadelphians live in poverty. Meanwhile, black-owned businesses have noticeably less access to capital to grow, one of the reasons behind the appallingly low percentage of black entrepreneurship in Philly.

As a Southern Poverty Law Center report explores, the American education system overall isn’t doing the best job teaching these essential facts, which might explain why the general public still ignores or rejects black pain.

Black History Month’s objective was to give American society an aid, a textbook, to maneuver itself through all that, to eventually eliminate the disparities and bring an end to the legacy of both overt and covert racism in America. This is just as important an exercise for whites as it is for African Americans. Knowing that history, establishing a complete understanding of it, helps remind everyone how much we’re all obligated to create optimal, equitable conditions.

The current modern manifestation of Black History Month isn’t doing that.

Contemporary celebrations of black history have a troubling tendency to confine that history to what’s happened over the past 500 years in North America. There’s little effort put into learning more about the vast history of African-descended people before they even arrived in the Americas, no extensive illustrations or deep digs into the complex civilizations and rich nation states that ruled the vastness of the African continent.

![]() I recall, as a teenager in the 1980s, a noticeable emphasis on that thousands-years-long history, the result of an academic explosion of major black scholarship on the ancient “Afrocentricity” of Black History.

I recall, as a teenager in the 1980s, a noticeable emphasis on that thousands-years-long history, the result of an academic explosion of major black scholarship on the ancient “Afrocentricity” of Black History.

Indeed, Philadelphia was one of the major hubs of that movement, from Molefi Kete Asante’s Afrocentric studies to black Philly community pride in visualizations such as The Moor hanging in the Philadelphia Art Museum, or the small network of struggling but reliable black bookstores always making reads from Chiekh Anta Diop, Ivan Van Sertima and John Henrik Clarke—to name just a few—available.

Your blackness was measured by the size of your “African-centered” library in those times. These days, blackness, and the observance of Black History Month, is measured by mass commercial themes, endorsements and the size of your black celebrity. Now, it’s relegated to individual achievements versus an embrace of our collective struggles. We’re moving farther and farther away, with each passing year, from knowing about those struggles.

There are points of pride here in Philly. The School District was the first major system to institute a mandatory black history curriculum; this week, for many teachers in the system, is a Black Lives Matter Week of Action. There’s been a resurgence of black-owned bookstores, from Uncle Bobbie’s in Germantown to the new Harriet’s Bookshop in Fishtown, to nearby Amalgam Comics.

Councilperson Isaiah Thomas is spending the month highlighting these and other black-owned businesses throughout the city, to encourage Philadelphians to not just buy local, but to buy black and local.

What those speak to is what we need most here, what Black History Month was supposed to be about: A year-long commitment to upholding what Woodson originally intended, for black people to be taken seriously, respected as equals and able to live unencumbered by the legacy and current reality of white supremacy.

Until we can do that, Black History Month is nothing more than a cultural birthday party.

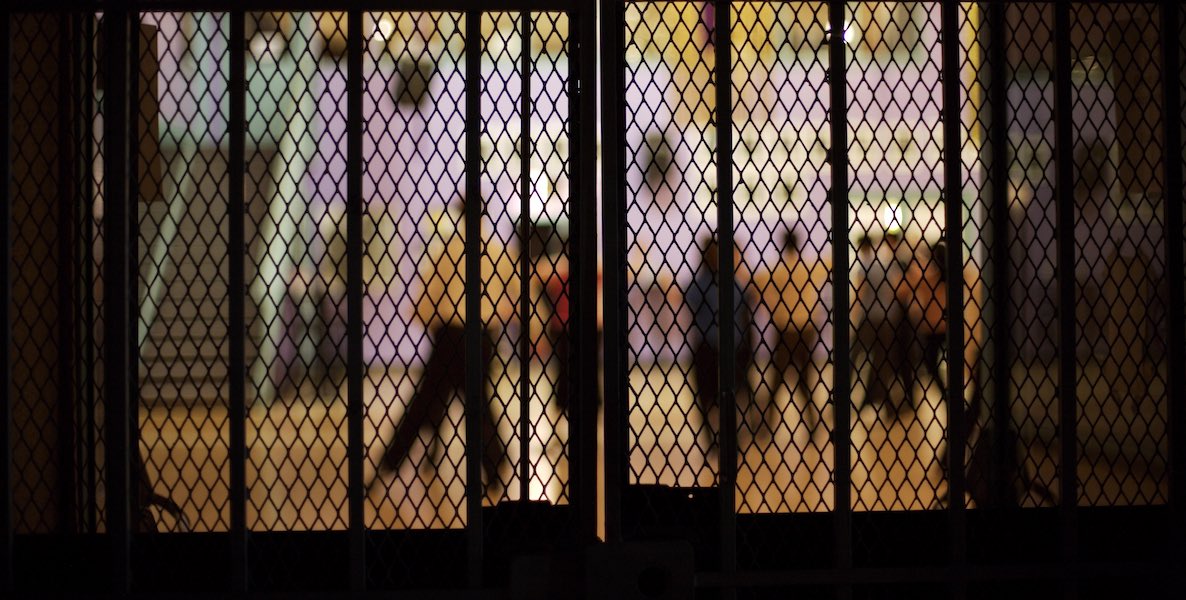

Header photo courtesy Kevin Burkett / Flickr