Dr. King died by the gun. He was assassinated on April 4 1968, nearly 54 years ago. He is one of the most famous American victims of gun violence. At the time of his death, he was an avowed pacifist who evolved his stance on gun ownership in the face of overwhelming threats of violence and death directed at him, his family, and all who worked with him in the Civil Rights Movement.

Years before his assassination, Dr. King was a fearful gun owner desperate to protect himself and his family. But over time he understood that fear was both a tool of the oppressor and a deeply internalized trait of white supremacy, against which he would fight until his dying breath.

This not-so-famous quote from King signals a critical point in his evolution on the subject of gun ownership for self-defense:

I was much more afraid in Montgomery when I had a gun in my house. When I decided that I couldn’t keep a gun, I came face-to-face with the question of death and I dealt with it. From that point on, I no longer needed a gun nor have I been afraid. Had we become distracted by the question of my safety we would have lost the moral offensive and sunk to the level of our oppressors.

Dr. King believed in his right to own guns in order to defend himself and his home. But after his Montgomery, Alabama home was fire-bombed, he had to come to terms with the vitriolic levels of violence to which he and his family were directly exposed. There is not a handgun in the world that can defend against a bomb attack.

RELATED: A timeline of how Philly helped shape Martin Luther King Jr.

What is most striking about this particular King quote are the implicit insights on his own fear and why he ultimately had to situate his personal security within the almighty context of his Christian faith. King’s fear when he owned guns—and by some accounts he owned an arsenal —had everything to do with what he faced daily in terms of threats against his life. He was in the belly of the American racial beast, and it was clear then that he had no intention of backing down.

King was well aware of the data on guns in homes, that mostly, people who keep guns in their homes use them on themselves and/or their family members. It was the same then as it is now. People shoot themselves, or their loved ones, intentionally or accidentally, far more regularly than they do intruders, tyrannical governments, or even hateful white supremacists.

King’s need for self-defense was not theoretical, and in this sense, it was much more difficult for him to idolize the Second Amendment.

His fear then, was as much about what was at stake for him and his family in that moment, a moment that literally exploded like a bomb in his home. From that point forward, Dr. King knew that his personal security was no longer a mundane phenomenon. He also knew that there was only one way that his life would end: in violence.

King’s application for a concealed carry permit in Montgomery Alabama was famously denied by the local sheriff’s office. He was deemed “unsuitable;” that is, he was a Black person who wanted to defend himself and his family from the violence of racism and white supremacy.

Herein lies an important distinction for King. He was a warrior for equal protection under the law and a racially equitable arrangement for American citizens. But his need for self-defense was not theoretical, and in this sense, it was much more difficult for him to idolize the Second Amendment.

King embraced the Second Commandment—thou shall have no other gods before me—as he foresaw the national consequences of America’s embrace of the Second Amendment. The Second Commandment is complex, but in short it forbids the worship and idolization of man-made things, as if they were gods. There are plenty of man-made idols in America, but none have reached the level of false divinity that guns and gun culture have in our national consciousness.

RELATED: Maj Toure’s Black Guns Matter flips the script on guns in urban areas

Second Amendment advocates often push the narrative of self-defense against the tyranny of government or the unchecked criminal elements amongst us. But King’s desire for self-defense was more specific—more targeted, if you will. Dr. King knew who was trying to kill him. There was no amorphous boogey man driving his need for self-defense and protection. Racist white power and privilege were the monsters prepared to cut his life short, and ultimately those forces did just that.

Having a permit to carry a concealed weapon would not have saved King’s life. Plenty of supporters around Dr. King were gun owners and many people engaged in the Civil Rights movement believed that gun ownership was a critical right for those folks who were directly engaged in the war against white supremacy. There are not enough good people with guns, perfectly placed in each iteration of American gun violence to ward off the carnage associated with our national gun-love affair.

King died a hero to many and over time he has become America’s perfect martyr. His national holiday has been sanitized to such a degree that Fortune 100 companies can claim social justice victories by giving their employees one day off for community service, once a year. But observers of Dr. Martin Luther King Day would do well to remember that although the man who assassinated King lived some part of his life in infamy, he too was seen as a hero to too many Americans than we might be willing to admit—back then in 1968 and maybe even now in 2022.

King was not born a pacifist. How he evolved on gun ownership and that evolution warrants much more exploration and skepticism.

Dr. King was an exceptional American who gave his life in the service of dismantling the contradiction of American exceptionalism. Two things are becoming more and more clear as the image of Dr. King and the MLK holiday become cleaner and more palatable.

First, King was not born a pacifist. How he evolved on gun ownership and that evolution warrants much more exploration and skepticism. His pacifism has defined almost every movement for equal rights that followed the Civil Rights Movement. And maybe, just maybe, it is time to revisit and rethink pacifism and/or non-violence as governing principles of organizing against oppression.

And this bleeds directly into a second issue that has been clarified in the proximity of January 6 to the national King holiday. The contemporary attempt to overthrow American democracy may have just been a practice run. For too many Americans, the events of that day in 2021 have been overblown by the current administration and overplayed by the American media.

But what January 6 represents is an important counter narrative to the pacifist approach to organizing in the struggles for (or against) democracy. The entities that organized January 6 are the enemies of Dr. King’s life’s work. They are the ideological descendants of those same American’s who aligned themselves with King’s assassin.

In the end, reducing King’s legacy has always created pitfalls along the path of the universe’s arc. But that arc can’t bend towards justice without more intention and maybe more force from those who seek to extend the life of America’s democratic experiment.

![]()

RELATED

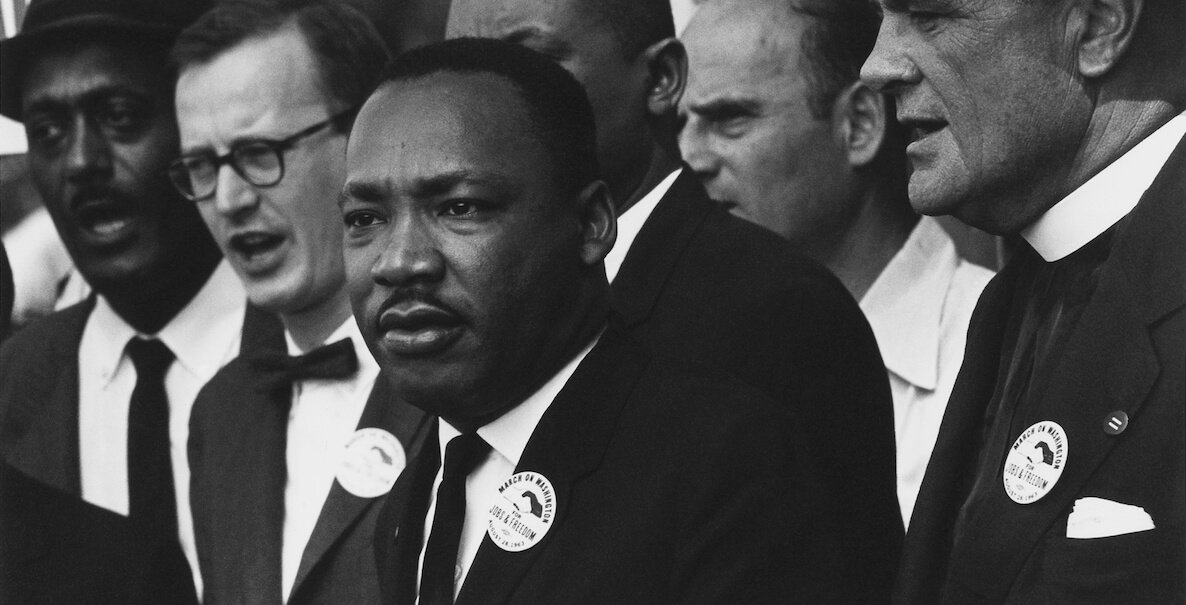

Header photo: MLK at the Civil Rights March on Washington