One of Philadelphia’s early graffiti innovators hasn’t been seen on the streets in more than 30 years. Throughout the 1980s, Spel (née Hernan Cortes) was a respected graffiti writer and breakdancer, selling custom clothes to the drug dealers on his block, esteemed by his high school art teacher, and occasionally pestered by Mural Arts’ Jane Golden to give it all up and paint murals with the Philadelphia Anti Graffiti Network.

Then, in 1990 Spel was arrested and convicted of second-degree murder and sentenced to life without parole. Spel maintains that he was wrongly convicted, caught in a web of corrupt policing. His lawyers at the Pennsylvania Innocence Project have been fighting for his release for 15 years.

In the meantime, Spel has adapted to making art under the restrictions of incarceration. While at SCI Graterford, he was a core member of the lauded Mural Arts Philadelphia restorative justice program that brought together incarcerated men with victims of crime and victim advocates. Today, while at SCI Dallas, he remains an innovator, finding ways to produce complex works despite limited access to materials and the struggle of simply finding a quiet space to work.

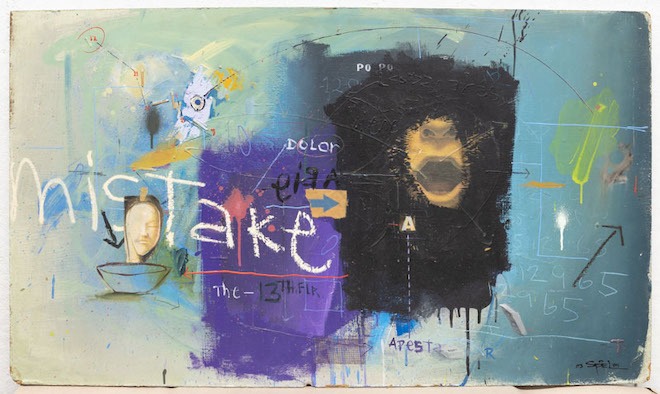

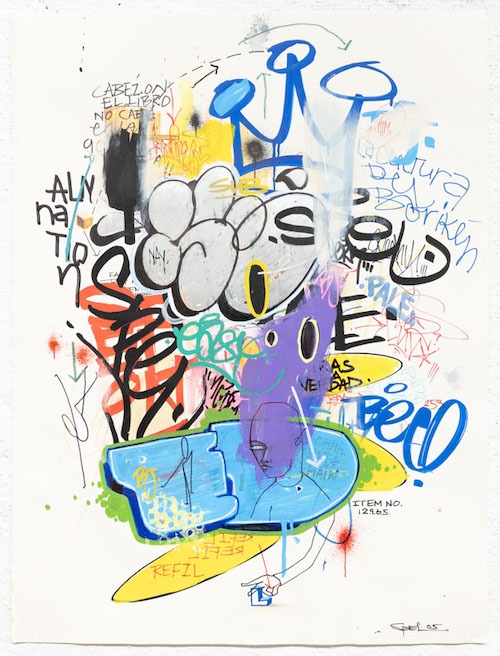

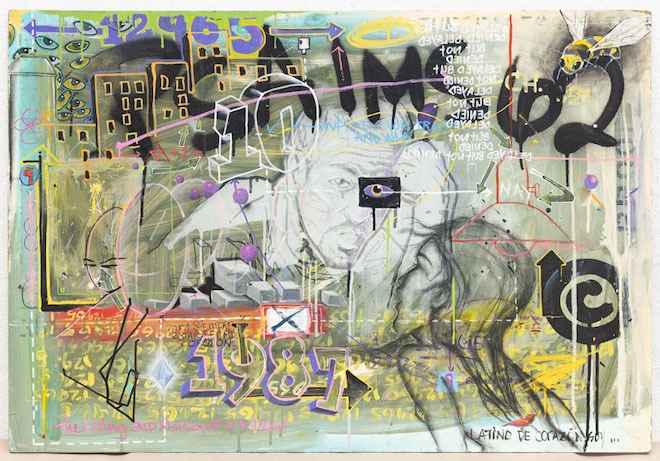

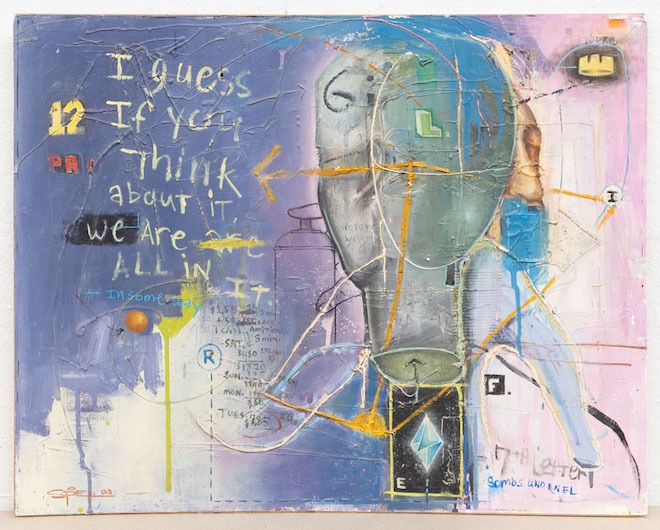

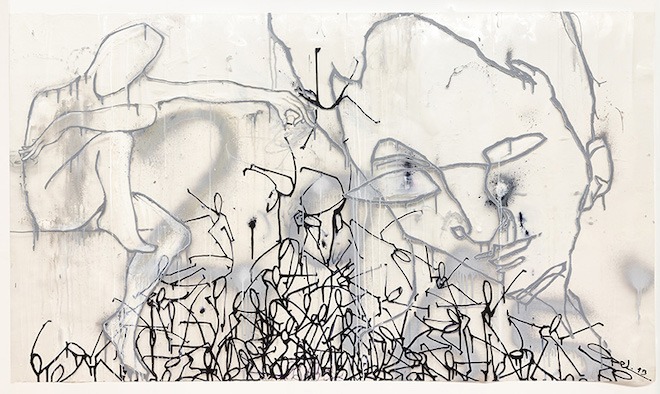

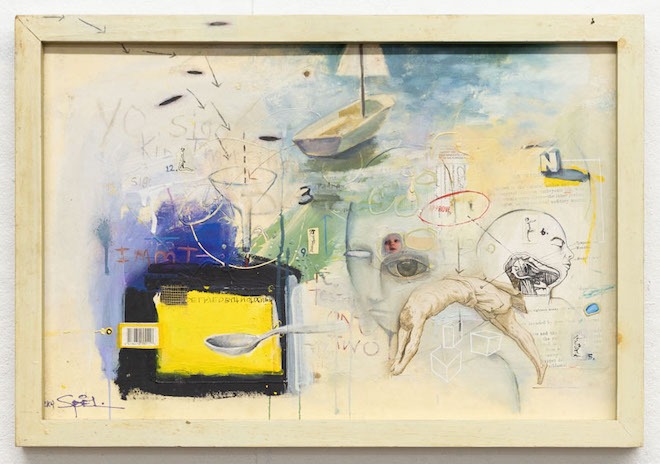

Over Zoom (yes, that’s an option for prison visitations), Spel talks a mile a minute, often jumping from topic to topic. You can see that lively mind expressed in his paintings, where a single work can incorporate graffiti lettering, realistic figure drawing and abstract expressionism. Spel pieces it all together. Now that he is at SCI Dallas, Spel’s access to art supplies is especially limited. He’s gone from having access to a studio with professional-quality paints to drawing on sheets of toilet paper.

While there is a surprising amount of joy in Spel’s work (breakdancers are a recurring theme), it’s the depictions of time marching on and a continued hope for the future that really stand out. Those paintings share stories of waiting for a justice system to finally provide Spel with justice, the rhythm of prison and the rhythm of being told “no” year after year, and dreams of walking through a city he hasn’t stepped foot in for decades.

At a moment when much of the country is worried about losing various freedoms, Spel embodies the oft-quoted line from Toni Morrison: “This is precisely the time when artists go to work — not when everything is fine, but in times of dread. That’s our job!”

As part of a partnership with Forman Arts Initiative, The Citizen caught up with Spel. The interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

RJ: Where did it all start for you?

Spel: The year was 1980 and I was living in Rhode Island. I was introduced to hip hop, and I loved that it covered every category in the arts: music, dance, visual art and fashion. I fit right in. I was already a kid who favored the arts over sports. I developed quickly, especially my breakdancing moves and graffiti skills.

In 1983 at the age of 15, I moved back to Philly, to Hunting Park. I arrived with zero friends, but I got to know people through dance. Within a year, I was crowned the best b-boy in the city and had formed one of the first b-boy crews in Philly. I was also honing my graffiti skills and trying to go all-city. I painted in North Philadelphia, South Philly and anywhere else I could travel to.

The other side was that, by 1984, I was also hustling. Us poor kids were enticed by this lucrative new market. It was easy. We were already hanging out on the corners, dancing and doing our thing, and the older guys capitalized on that.

Someone might say, “Hey, do me a favor. Hold this money and I’ll give you 50 bucks at the end of the day.” Of course, I said yes. And those guys were our role models. I remember the first time I tried selling. I got booked that same day. But I kept at it. So I lived in two worlds. I had aspirations of making it in art, and there was also a world of black market pharmaceuticals. It was a vice that kept pulling me back in. Now, I recognize that I was part of a destructive element in the community. Nothing to be proud of, but it happened.

Did you have people in your life who supported your art?

I had an art teacher, Ms. Horn from South Philly High, who let me experiment in her class. I would knock out her assignment, and then I had free reign. I kept her closet full of spray paint. I’d be in the back spraying away. And she knew I was active on the street. She’d yell out, “Spel! If you were doing that on the street, you would’ve been caught by now.” And I’d say, “Ms. Horn, that’s why I’m here. Getting my speed skills up.”

Ms. Horn was a major inspiration to me. She opened my eyes to artists like Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Kenny Scharf, who had transitioned from the streets into galleries and museums. I also saw graffiti artists like Dondi, Crash, Rammellzee, Pink and Futura making that transition. Those artists inspired me to develop into a young entrepreneur and serious fine artist.

“I will be one of the voices showing the world that there’s good coming out of Philly.” — Spel

How did you turn your graffiti into a business?

I made custom clothing. The other writers painting on clothes used airbrushes, but I didn’t believe in airbrushes. It felt like cheating. I stuck with spray paint. Using a spray can, particularly the industrial cans and caps we had back then, was already challenging. Pulling that off on a t-shirt showed real talent. That all helped me stand out.

At first, I was painting entirely freehand, just showing off my technique. Then, with some encouragement from Ms. Horn, I began cutting stencils and spraying out geometric shapes. I would layer that all together, almost like a puzzle. It was one-off abstract art on clothing.

Were your clothes popular?

Business took off immediately. I went out to all the drug dealers on the corners and they started buying my stuff up. I was living the dream, and I did that for about three years. When things were going well, that meant no more selling drugs. But when the clothing business was slow, hustling supplemented my income. If I had had a little more stability or some savings, I could have started screen printing and mass producing. I never quite got there.

Your work has evolved a lot since then. These days, what is your art about?

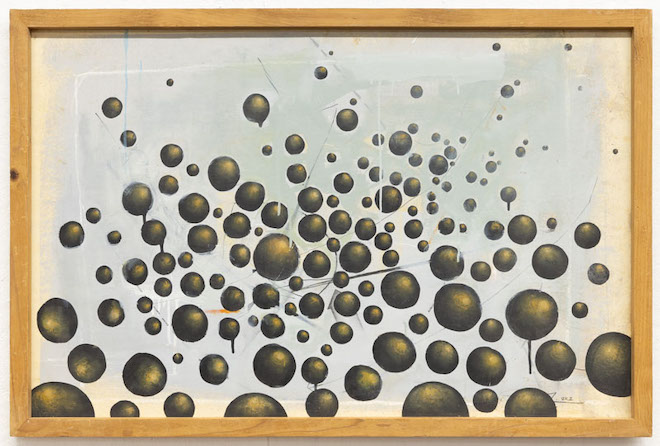

When creating, I am less the author than I am a companion, being led in spirit to channel whatever the content may be with any given work. I believe good art provokes thought, challenges views, penetrates the heart, and possesses the ability to provide answers that books and technology cannot. My work portrays experiences from both the community inside (prison) and outside (the free world), and the subjects are universal but personal: TIME (This Is My Experience); the ephemeral and the infinite; life and death; truth and lies; struggles and hardships, and lessons learned. The work is about my journey, and also our journey.

What is it like making art while incarcerated? How is it different from making art when you’re free?

It’s a challenge. You’re dealing with the rules of the authority, and you’re also dealing with the rules of everyone else who is incarcerated with you. Those are some delicate things to navigate.

Mostly, you have to be resourceful and make the most of what you’ve got. Prison is a noisy place. If you need quiet to concentrate, that means working late nights or early mornings. We also have restrictions on materials, so you become good at salvaging the scraps around you and determining if what you’ve found might be considered contraband.

It’s common to hear an artist say, “I make my best work when I’m facing constraints.” Often, that’s an artist creating certain rules for themselves. You did that with your clothing business, insisting on using spray paint. But with all of the restrictions that are imposed on you, I am amazed that you have the space, and the mental energy, to be creative.

Once I get into the zone, I just keep going. I’ve seen individuals who fear a blank canvas. I attack it. And I cherish that feeling. When I’m told, “No, that can’t be done,” or when I’m limited, that’s when I’m at my best. And that grittiness shows up in the artwork, so it’s all good.

Where do you see your art going, particularly once you’re released?

Well, I’d be a fool to start painting illegally again. Yes, there’s an adrenaline rush behind graffiti, but I’m 56 years old. How would I look, painting without permission? There ain’t that much rebel in me.

I love my daughter Nadine and my two grandkids, Payton and Jaxson. My aspiration is to be reunited with them. I look forward to following in the footsteps of my brother Eddie Ramirez, who served 27 years of a life sentence and was finally exonerated in December of 2023.

As far as art, I just want to continue the work. The foundation has been laid here, but I want to get my art out to the public, in galleries and through murals. If this is what I can do behind iron, steel and concrete, there are no excuses. I will be one of the voices showing the world that there’s good coming out of Philly.

RJ Rushmore is a writer, curator and public art advocate. He is the founder of the street art blog Vandalog and culture-jamming campaign Art in Ad Places. As a curator, he has collaborated with Poster House, Mural Arts Philadelphia, The L.I.S.A. Project NYC and Haverford College. Rushmore’s writing has appeared in Hyperallergic, Juxtapoz, Complex and numerous books. He holds a B.A. in Political Science from Haverford College, where his thesis investigated controversies in public art.

Corrections: Attorneys from the Pennsylvania Innocence Project represent Spel, whose birth name is Hernan Cortes.

This story is part of a partnership between The Philadelphia Citizen and Forman Arts Initiative to highlight creatives in every neighborhood in Philadelphia. It will run on both The Citizen and FAI’s websites.

![]() MORE FROM OUR ART FOR CHANGE SERIES

MORE FROM OUR ART FOR CHANGE SERIES