The 2019 Municipal Elections finally came to a close with a big surprise on Tuesday with the election of Kendra Brooks, one of two Working Families Party candidates, over Republican Al Taubenberger for one of the two At-Large Council seats that have historically been held by Republicans. This culminates an election season that ushered in lots of other big political changes too, in both Philadelphia and the broader region. Here are a few of our big takeaways from a momentous year in local politics.

1. City Council is Undergoing a Huge Generational Change

With four newcomers joining Council in January—Jamie Gauthier, Katherine Gilmore-Richardson, Isaiah Thomas, and Kendra Brooks—there will now be seven members who are in either their first or second term. This is a major shift from eight years ago, and slowly but surely, the average age on City Council is dropping and becoming much more representative of Philadelphia’s generational make-up.

Due to our lack of City Council term limits, Philadelphia has had one of the oldest City Councils of any big city in the country, with many members thinking of their Council service as a lifetime appointment instead of a tour-of-duty. That’s kept a lot of new ideas from cycling into the political system at a healthy clip, and has also kept a lot of old discredited ideas on the agenda. The recent failed push by Darrell Clarke and Jannie Blackwell to increase minimum parking requirements for new homes is a great example of a bill that older members loved, which probably falls off the agenda completely in the next Council term with more younger members in the mix.

The 2019 elections will very likely be seen going forward as a turning point where a lot of the mythology about untouchable incumbents began to melt away, and a new era of more competitive and accountable local politics began to take hold.

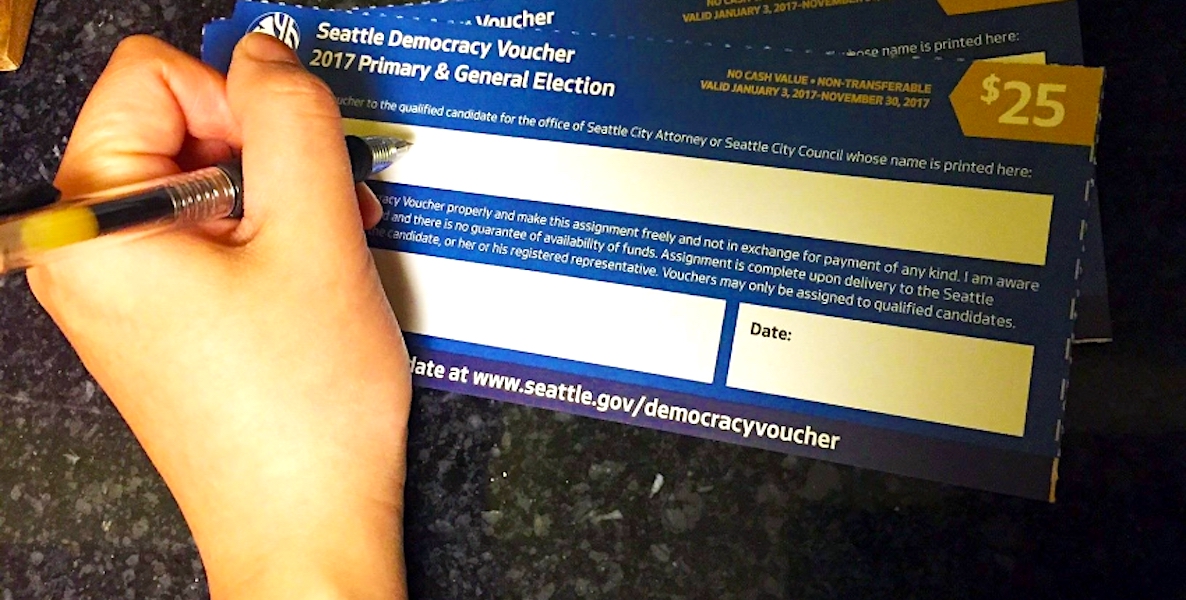

With that generational shift, there’s also an unmistakable shift to the political left on a number of issues, and we’re likely to see more campaigns this term in the same vein as prior efforts like Paid Sick Leave, Fair Work Week, and the Domestic Workers’ Bill of Rights, especially now that a Working Families Party member has been elected to Council. The national Working Families Party organization is a major supporter of these kinds of campaigns, and big-city legislatures are a natural base of support for them. At the same time, the 2019 elections really didn’t result in much of a net gain for candidates of a more populist flavor. Of the new class of politicians coming in, only Kendra Brooks could really be described as a populist, and even her messaging on the issues seemed more pragmatic than what we heard from some of the more populist candidates who ran in the primary. The others seem dispositionally to fit more in the problem-solver and bridge-builder mold of elected official.

2. “Liberal Wards” Continue to Be a Political Force

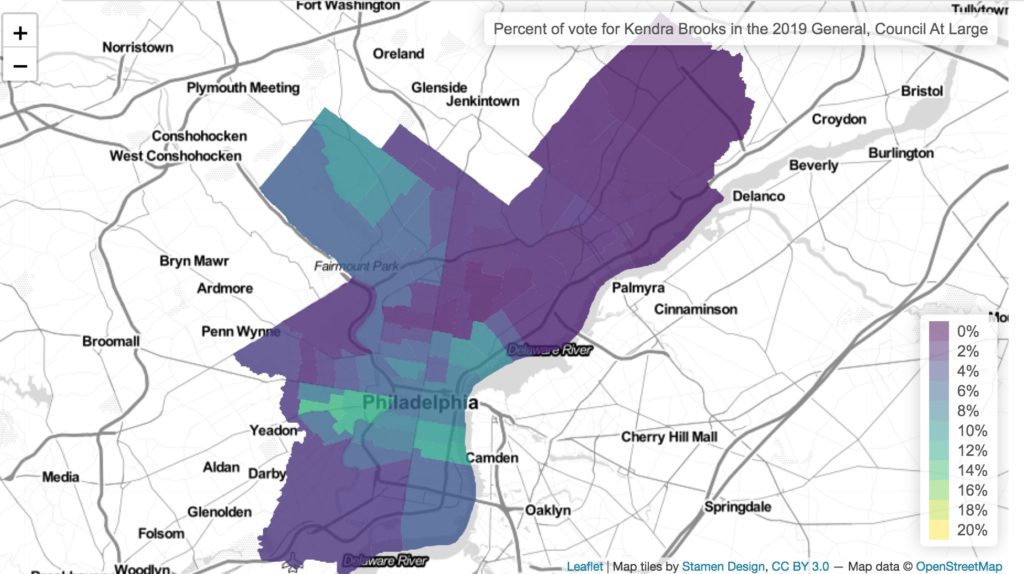

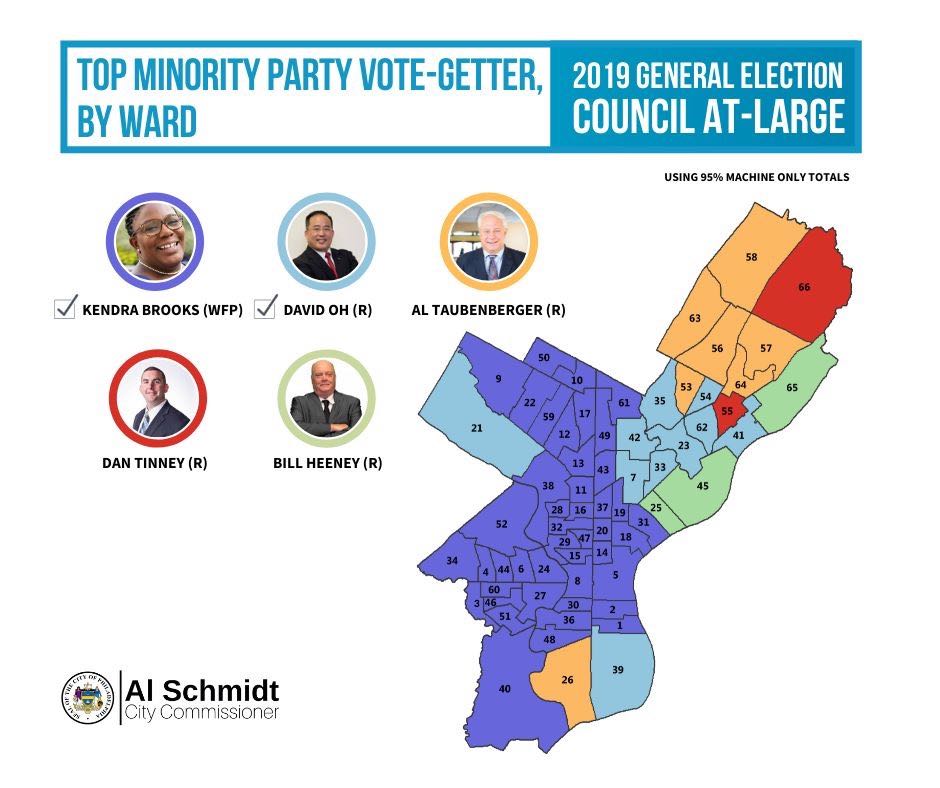

To use Bob Brady’s terminology, it was the usual “liberal wards” that gave Kendra Brooks the most votes, which are the backbone for any progressive candidates’ citywide campaign. These are mainly located in Center City and the neighborhoods ringing it, eastern South Philadelphia, the Baltimore Avenue corridor in West Philadelphia, and the 9th and 22nd wards in the Northwest covering Mt. Airy, Chestnut Hill, and some of Germantown. Brooks was able to expand on this base into even more areas, and particularly more areas of West Philadelphia.

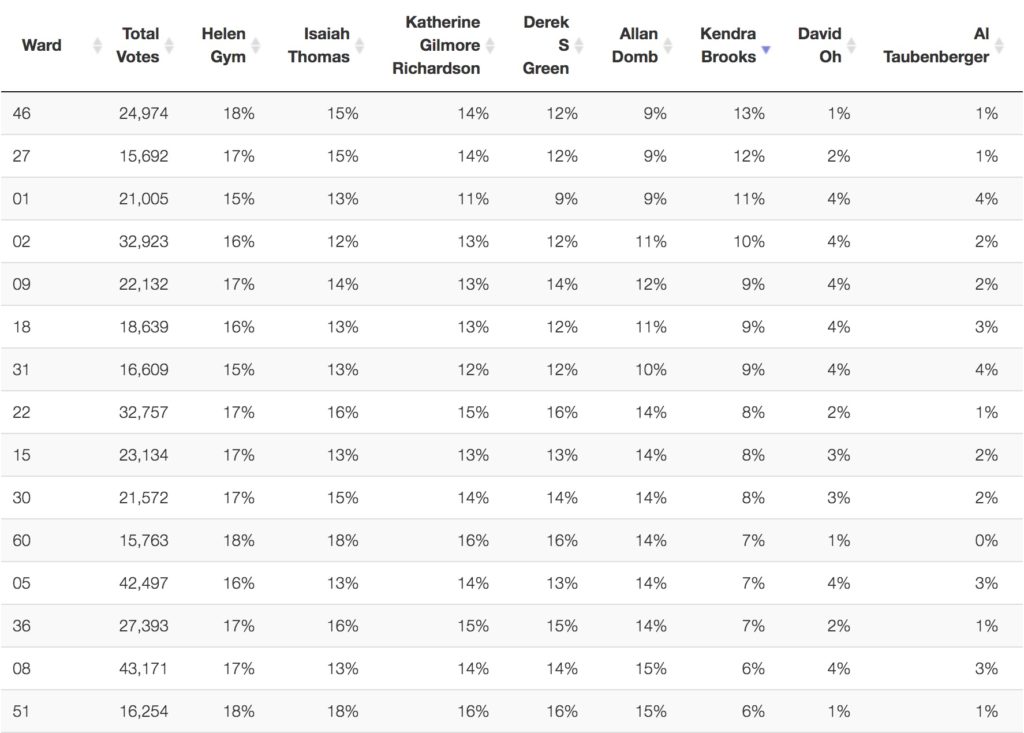

From the Sixty-Six Wards Ward Portal, here’s a list of wards ranked by their support for Brooks. The newer ones on the list that you don’t always see among the usual suspects for citywide progressive candidates are 51 and 60 in West Philly, and 22 in the Northwest. Jamie Gauthier also won the 51st and 60th wards in her 3rd District Council primary.

In the primary, this cluster of wards wasn’t able to elect one of their most-preferred candidates to one of the two open At-Large Council seats, as the votes were split several ways between Justin DiBerardinis, Eryn Santamoor, Erika Almiron, and a couple others, but they’ve had elevated voter turnout for several years now and have powered some primary challengers. At this point it feels like a stable feature of our elections that these wards will make up a large and growing share of the vote even in odd years.

3. The More Conservative Northeast and South Philly Wards are a Weaker Citywide Force

Mayor Jim Kenney won his reelection campaign while losing seven wards on Tuesday, most in the Northeast, but also in the 26th ward in South Philadelphia, which includes Girard Estates. It was the first time since 2003 that the Democratic nominee for Mayor lost any wards. Michael Nutter lost zero wards in both of the general elections he ran in, and only Republican Sam Katz was able to win some wards away from John Street in 2003.

Without any polling on the race, we can’t say for sure why these areas turned against Kenney, but there are any number of hot-button issues that we can infer might have played a role: the soda tax, his strong support for Philadelphia’s ‘sanctuary city’ status, the safe injection sites debate, Kenney’s support for moving the Frank Rizzo statue away from the Municipal Services Building, or just the growing influence of national politics on local politics. Both these areas voted for Donald Trump at much higher rates, and Republican Mayoral nominee Billy Ciancaglini ran on a more-or-less Trumpy platform.

But ultimately it just didn’t really matter to the citywide results. Ciancaglini didn’t come close to beating Kenney. Al Taubenberger was the top vote-getter in several Northeast wards and also the 26th ward, and he still lost his seat to Kendra Brooks even though turnout in those wards actually increased from 2015. The turnout in “liberal wards” just increased by a lot more.

4. All the Southeast Counties are Controlled by Democrats Now, and the SEPTA Board Will Flip Too

Regionally, the biggest news of the night was that all four of Philadelphia’s collar counties—Delaware, Montgomery, Bucks, and Chester—will have Democratic majorities in County government for the first time. In Delaware and Chester, Democrats have never had a majority.

That’s an enormous change that could have big implications for the 2020 elections, both at the Presidential level and down-ballot races for state legislature. And from Philadelphia’s perspective, unified partisan control of local governments across the region at least has the potential to bring the suburban counties more into alignment with Philadelphia on more regional goals for the environment, economic development, and transportation.

Mayor Jim Kenney won his reelection campaign while losing seven wards on Tuesday. It was the first time since 2003 that the Democratic nominee for Mayor lost any wards.

One concrete change that will result from this is that for the first time, Democrats will appoint a majority of the SEPTA Board members starting in 2022 when some of the current Chester County board members’ terms expire. As The Inquirer’s Jason Laughlin writes, it’s unclear whether that partisan realignment will mean any major policy changes when the main axis of policy conflict on the Board is still urban vs. suburban interests, but it’s possible that Democratic politicians will be more ideologically available than their Republican counterparts for some of the changes needed to grow transit ridership, and for some of the difficult revenue and funding conversations not far down the road.

Zooming out, the 2019 elections will very likely be seen going forward as a turning point where a lot of the mythology about untouchable incumbents began to melt away, and a new era of more competitive and accountable local politics began to take hold.

Jon Geeting is the director of engagement at Philadelphia 3.0, a political action committee that supports efforts to reform and modernize City Hall. This is part of a series of articles running in both The Citizen and 3.0’s blog.