For many teens, turning 18 is a milestone marked by celebration, a rite of passage that comes with a sense of independence, freedom and excitement about the future.

On William Bentley’s 18th birthday, he woke up in the juvenile unit of a Philadelphia prison and was told he’d be moving to an all-adult unit, where he’d continue to be held until he could put up his bail.

Knowing this day would come, Bentley, who had been charged with aggravated assault, had been eating as much as he could and working out as hard as possible, hoping to get stronger and ward off fights.

But when he got to the adult unit, he realized no amount of pushups could’ve helped him: “These were full-grown men. I’m not going to lie: It was scary,” he says.

But the men didn’t go after him; instead, Bentley was looked after by older inmates, men who said that Bentley reminded them of their sons, their grandsons.

“You’re a baby, they’d say. If anyone tried to make trouble with me, someone would speak up and tell them not to mess with young bol,” Bentley recalls.

In 2019, 143 young people had cases that started out in the adult system. That number rose from 106 in 2018.

Instead, it was the prison medical system that nearly cost Bentley his life.

For eight days, the teenager was given the wrong pill, a purple one in place of the teal one he typically took to manage his depression and anxiety.

By the eighth day, he started having muscle spasms; he couldn’t walk, he couldn’t talk. His tongue swelled, making breathing difficult. He spoke up, but no one believed him. They said he was faking. They sent him to the mental health counselor, who promptly returned him to his cell.

Family on the outside called Pennsylvania Prison Society, which ultimately got Bentley sent for testing and evaluation at the prison hospital.

For two months, he slept in a prison hospital bed, one ankle and the opposite wrist handcuffed to his bed, IV fluids working through his system to flush out the toxins he’d ingested because of the medical error.

![]() He felt hopeless, ready to take a deal that would send him to state prison for what he hoped would be no more than seven years, if he maintained good behavior.

He felt hopeless, ready to take a deal that would send him to state prison for what he hoped would be no more than seven years, if he maintained good behavior.

Then two representatives from Philadelphia Community Bail Fund came to see him, and told him that, for the 2018 Holiday Bail Out, Sarah wanted to bail him out.

“Sarah?” he said. “You mean the person who does the art with us?”

Sarah is Sarah Morris, the co-director and one of the five co-founders of the Youth Art & Self-Empowerment Project (YASP).

The nonprofit’s efforts are multifaceted: They hold Saturday art and poetry workshops every single week without exception for youth who are being held in adult prisons. Through the workshops, they get young people expressing themselves in ways they may never have done before.

“That’s one of the issues with our communities in general,” says YASP co-founder and co-director Josh Glenn, who’d also been arrested and held at both youth and adult facilities. “A lot of folks are taught not to cry, not to show their emotions, and I think that bottles it up and creates conflict.”

That YASP spends time with young people on State Road, for example, gives them a sense of the rings of support and community that are being built around them.

Studies have shown the benefits of art on incarcerated people, and Joanna Visser Adjoian, co-director of Youth Sentencing and Reentry Project (YSRP), says that the impact of YASP’s work is readily apparent.

That YASP spends time with young people on State Road, for example, gives them a sense of the rings of support and community that are being built around them.

“The fact that YASP provides those powerful workshops that they do, on Saturdays, when other programming’s not being brought in, specifically designed and aimed at the young people who are in adult custody, has a profound impact on the time that they’re being forced to stay there, but also on the broader advocacy efforts that are happening on their behalves,” Visser Adjoian says.

There is also the Tuesday Youth Justice Hub, workshops to help youth charged with crimes and their families understand and navigate the complex court process.

There is the guide they’ve created to help youth coming out of the criminal justice system find essential resources, from mental health support to employment.

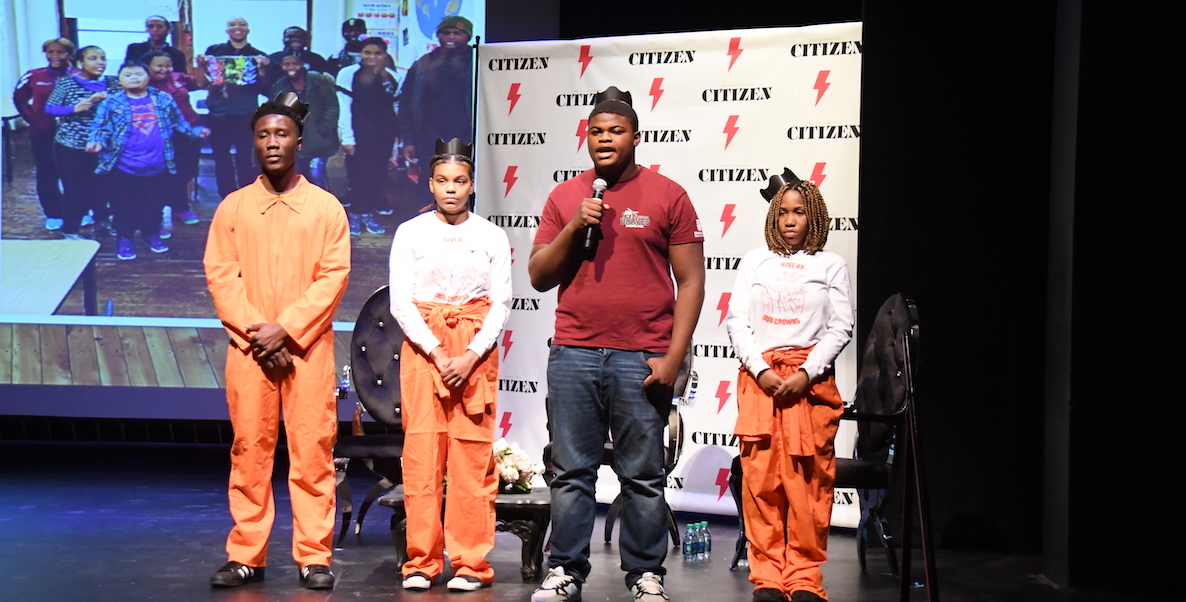

![]() YASP regularly welcomes youth coming from the system to work for them as community organizers, long-term or until YASP has helped them uncover their bigger-picture passion.

YASP regularly welcomes youth coming from the system to work for them as community organizers, long-term or until YASP has helped them uncover their bigger-picture passion.

And there is the advocacy work they’re doing to repeal Act 33, a state law that allows young people’s cases to be filed directly in adult court, despite scientific evidence — and even a Supreme Court ruling — that brain function is not fully developed until people are 25 years old.

That Supreme Court case, in 2017, banned the practice of sentencing juveniles to prison for life without parole — something especially egregious in Philadelphia.

“For a youth case to be filed in adult court should be the rare exception, not the norm,” says Morris. She and her team were heartened, at a rally on MLK Day, to hear Councilmember Helen Gym call on District Attorney Larry Krasner to stop filing so many cases, and speak up about how shameful it is that Philly is holding youth in adult jails.

Glenn, as well as Jasmine Jackson, Victor Saez and Zachary Banks, were all arrested as minors and spent time in adult prisons; they met Morris when she was a fellow for a now-defunct organization that brought poets and artists to the prisons.

When Glenn, Jackson, Saez and Banks were released, they and Morris got together to talk about the importance of continuing the workshops, and working toward big-picture system change that would help youth get the support they need to avoid the criminal justice system.

They formed YASP in 2006, and have grown it from a side project to a nonprofit that’s funded through grants and personal donations like those from Bread & Roses Community Fund, Public Welfare Foundation, Borealis Philanthropy, the Hive at Spring Point (which is also a supporter of The Citizen), the Eagles, the Philadelphia Foundation’s Youthadelphia Fund, Resist Inc, and the Circle for Justice Innovations.

Last year, they reached 75 youth through their art programs; bailed out 11 more through their partnership with Philly Community Bail Fund; supported 26 families through the youth participatory defense hub; provided direct reentry support to 15; and they have employed 20 formerly incarcerated youth at YASP since 2006. They also connect with approximately 500 young people each year through workshops in local high schools.

“If we lock a young person up, we hold them back from connecting to all of the resources that could help them change and grow,” Glenn says. “We need to change the process.”

Glenn says that once he was released and took on the task of learning about the history of minorities — Black people, Brown people, Latino people, Jewish people, and more — there was no turning back. “I looked at all the ways that the system has held our communities back, and I just had to do something about it,” he says. “And we all have that power, that ability to change minds and change hearts and empower people.”

YASP has seen progress in their time doing this work, but not enough. At any given time in Philly, there are about 20 people who were arrested as youth sitting in adult facilities.

Twenty may not seem like a lot on paper, but, as YSRP’s Visser Adjoian explains, over the course of a year, that’s several hundred lives that are forever changed, each of which has a ripple throughout his or her family and community.

In 2019, 143 young people had cases that started out in the adult system (that number rose from 106 in 2018).

“Our goal is to repeal Act 33, but the longer-term goal is to get young people out of prison — period. We need to transform our system to one that holds people accountable, but also helps them heal,” says Glenn.

Morris notes that if you look at the reasons why most young people commit crimes — the need for money, or trauma or anger that they don’t know how to deal with — most are reinforced by putting someone in jail. Especially in adult jails, young people are exposed to more trauma, which makes them less able to sustain themselves legally once they have a felony conviction.

“We want to show the young people we work with that we see them and don’t just see these pieces of paper of whatever the charge is,” she says. “They’re still a child, they’re still a young person who has potential and who we shouldn’t turn our backs on because they made a mistake or may have been caught up in something that wasn’t their fault.”

![]() Among the team of YASP employees who now runs the Tuesday Youth Justice Hubs: William Bentley, now 19. YASP, he says, gave him hope. “They gave me that power and that will to keep going.”

Among the team of YASP employees who now runs the Tuesday Youth Justice Hubs: William Bentley, now 19. YASP, he says, gave him hope. “They gave me that power and that will to keep going.”

Freed last January, he was released in the clothes in which he’d been arrested — a T-shirt and no jacket — in the dead of winter. He made his way home and called Morris, who invited him to come to YASP’s Chinatown-based office to meet with her and the team.

There he met Glenn and staffer David Harrington. “They asked me what I wanted to do, and I told them I want to change the system,” Bentley says. “Nobody should ever be treated the way I was, whether they’re guilty or not.”

Harrington and Glenn saw Bentley’s determination and invited him to join the YASP team. All of them are determined to use their experiences to help others.

“If we lock a young person up, we hold them back from connecting to all of the resources that could help them change and grow,” Glenn says. “We need to change the process.”

Want more smart prison reform news? Read these related articles:

- Can basketball keep youth out of prison? It’s working in Richmond, Virginia.

- Let’s abolish prisons and spend that money to help prevent crime in the first place

- Reentry Project looks at how to keep the recently incarcerated out of prison

Correction: A previous version of this story misstated where William Bentley was on the morning of his 18th birthday. He was in the juvenile unit of an adult prison. It also failed to mention that Josh Glenn is co-executive director of YASP.

Photo courtesy YASP, the Youth Art and Self-Empowerment Project.