This week, I attended the Cornell Urban Tech Summit, which focused on the role of technology in helping cities adapt to climate change. It was a really good event, and I left feeling pretty pumped about the way that technology will be helpful to city governments and investors to advance urban resilience.

Projects like ClimateIQ are using AI to speed up the process of crunching data to help communities better understand their climate risk. As a collaboration between a number of universities and Google, ClimateIQ is also creating a free, open-source tool that will enable cities without millions of dollars in climate preparedness budgets to access these resources.

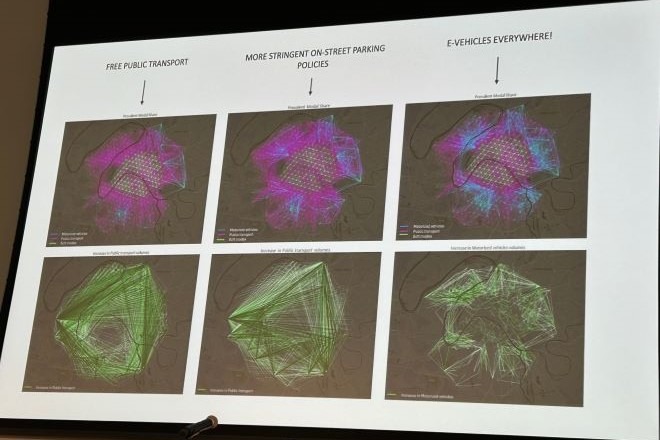

Digital twins are also being used to help cities better plan for climate change, moving past other kinds of modeling like GIS or CAD by working off real-time data. By creating a digital model of reality, digital twins can inform an array of decisions from transportation planning to real estate construction.

But as I listened to presenters, I found myself still grappling with the election two weeks earlier. Didn’t the outgoing administration make the largest-ever investments ever in climate resilience in the form of the Inflation Reduction Act and Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act — and get thanked for that with the election of a Donald Trump and his climate-change-is-a-scam, drill-baby-drill, end-environmental-protections, leave-the-Paris-Accords agenda?

Is the public paying attention to any of this?

Urban tech is great — but how do we thoughtfully communicate its power and potential to the general public?

In a shared keynote session with two federal administrators, the scale of the problem at hand and the need for trust in the government’s response were both evident. Kristin Fontenot, the director of the Office of Environment and Energy, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, shared a map of the 24 separate billion-dollar weather and climate disasters that impacted the U.S. through October 2024. Francisco Sanchez, associate administrator of the Office of Disaster Recovery & Resilience, Small Business Administration, noted that five years from now, these billion-dollar events are predicted to occur every seven to eight days.

Look at that map — most of the disasters are in red states! How can we better communicate that climate event mitigation, adaptation and recovery are by their very nature inflationary? That defunding the green economy makes just about as much sense as defunding the police?

The task at hand requires more novel methods of communication with the public than just charts with data and information. I was intrigued by the presentation by Ashley Louie, Chief Technology Officer, BetaNYC. BetaNYC is a civic organization dedicated to helping New Yorkers access information and use technology.

BetaNYC has developed a project, FloodGen, that uses generative AI photos to illustrate flood risk in New York City neighborhoods. The goal is to raise awareness of the potential for flooding in flood-prone neighborhoods, and empower leaders to seek resilience funding or otherwise advocate for themselves.

Is this an effective way to get people to take action? Not sure. But it’s a sign of the wild times we live in that we need generative AI images to convince people of reality. We all now have a hard time reading or listening to boring truths, but fictional images of disasters activate a dopamine rush, and by igniting our emotions, actually resonate with people.

Imagine if BeeBot could tell you on an extremely hot day that if you walk on the north side of 7th Avenue the street temperature is 5 degrees cooler than on the south side?

Later, Dennis Crowley, founder of Foursquare and Dodgeball, presented his new app, BeeBot, which made me think another new way of communicating about climate might come in the form of audio augmented reality. Though Crowley prefaced his pitch by saying BeeBot had nothing to do with climate, the app could easily serve to inform people about climate risk.

In brief, BeeBot is an app that is activated by your AirPods to notify you of interesting things that you experience walking around the city. Crowley saw that everyone walking around cities wasn’t just looking down at their phones, but they had AirPods in their ears. Simultaneously, he seemed frustrated that in order to activate ChatGPT or Siri other AI technologies, you had to ask questions of it.

Crowley wondered: What if an app fed you interesting tidbits as you walked around the city with your AirPods in? What if there was a social dimension to it, where the app collected snippets of impressions from your friends, or told you as you passed a coffee shop that your friend was there a week ago and liked it?

Normally I’m skeptical of social media, but I was convinced not only by Crowley’s presentation but by testing out the app myself.

Crowley and a Cornell Tech student, Andrew Park, created a sample tour on Roosevelt Island for conference attendees. As you walked outside the auditorium with your AirPods in and BeeBot activated, the app gave you helpful information — notes about the architecture, where public restrooms were, that there was a trash can up ahead. But when BeeBot included a note about how the Cornell Tech campus is elevated several feet above the 100-year floodplain, it hinted at the way that BeeBot or other apps like it could offer a climate lens on augmented reality.

I kept my AirPods in as I rode the subway back to Manhattan to get my train home to Philadelphia. I occasionally got notified: at 50th Street there was truffle pizza; at Bryant Park, a heavenly chocolate babka. Over time the idea is that BeeBot would learn your preferences — and hopefully would know that I’m not interested only in high-carb foods.

The app is also clearly in beta — a lot of notifications were more like “hallucinations” of places based on old data (perhaps from an old Foursquare database). When I got off the subway at 23rd Street, it told me to look out for Imagine Gallery — a place I couldn’t find in real life and seems to have closed about a decade ago.

But imagine if BeeBot could tell you on an extremely hot day that if you walk on the north side of 7th Avenue the street temperature is 5 degrees cooler than on the south side? Imagine if it nudged you that the AQI in your neighborhood is higher than that of another zip code because your neighborhood has more car traffic and they have more bike lanes? How might informational snippets like these — interspersed with fun facts about coffee shops you pass or what your friend thought about a clothing store across the street — change people’s feelings about climate change and how we use urban tech to respond?

BeeBot’s little intrusions were always welcome and when I took my AirPods off to get my Amtrak home, I felt a tiny twinge of sadness. AI is great, but dopamine might be greater still.

Diana Lind is a writer and urban policy specialist. This article was also published as part of her Substack newsletter, The New Urban Order. Sign up for the newsletter here.

![]() MORE FROM DIANA LIND’S NEW URBAN ORDER

MORE FROM DIANA LIND’S NEW URBAN ORDER