Over the past decade, Philly’s food scene has become crowded with ad-hoc food events: chefs with restaurants serving food at other chefs’ restaurants; cooks between jobs making old-school Italian American food in a random basement on a Tuesday night; breweries working with chefs to offer a special menu.

The culture of “pop-ups,” as these events are broadly called, seems endemic to the city’s food scene, a testament to the genuine friendships and interest in collaboration (rather than competition) among many of the city’s chefs, cooks, and business owners.

But what was once just an element, albeit a delicious one, of the city’s food culture has become a veritable onslaught since the pandemic began. The Instagram feed of any food-loving Philadelphian is inundated with new pop-ups of every kind: birria ramen, Filipino food, cheesesteaks filled with West African suya, pies that sell out faster than I can seem to send a DM, gorgeous spreads of Vietnamese springs rolls served with Hong Kong-style XO sauce, biscuits dripping with thick honey butter. The list goes on. (And, amazingly, it’s all top notch food.)

Where once the only aspiration in the restaurant world seemed to be to open a traditional restaurant, pop-ups are an indication that other futures are possible.

Why have pop-ups proliferated even as restaurants shutter? One clear answer is that laid-off and furloughed restaurant employees suddenly found themselves with no income, a lot of free time, and a desire to do something with all their pent-up creativity.

These typically one-person shows operate without much overhead, selling their take-out meals via social media and through the platforms of established brick and mortar hosts—who also benefit since pop-ups attract new customers.

![]() For some pop-up chefs, it’s a way for them to support themselves and give back to the community. For host restaurants, it’s a way to keep their business exciting to new and old customers. Some pop-ups chefs want to own a brick-and-mortar of their own, and some say the devastation of the pandemic has driven them to think outside the box.

For some pop-up chefs, it’s a way for them to support themselves and give back to the community. For host restaurants, it’s a way to keep their business exciting to new and old customers. Some pop-ups chefs want to own a brick-and-mortar of their own, and some say the devastation of the pandemic has driven them to think outside the box.

Eleven months into Covid, most business owners are beyond trying to predict what their lives will look like six months from now, but it’s clear that pop-ups are more than just a way to get to the other side of the pandemic: they represent a broader shift in how people in the food industry are conceptualizing what success looks like.

Where once the only aspiration in the restaurant world seemed to be to open a traditional restaurant, pop-ups are an indication that other futures are possible. Rather than grinding it out seven days a week in a brick-and-mortar, maybe it makes more sense to serve food out of a closed restaurant once or twice a week, or to run a food cart on weekends.

It’s not difficult to imagine a future where spaces (and overhead) are shared, where our favorite restaurants are amorphous and the focus is more on the food itself—and the team cooking it—than on the place where it’s cooked.

A symbiotic side hustle

Even the most in-the-know eater (or food writer) in the city is probably only familiar with the names of the people who run their favorite restaurants: the owners/head chefs. But the amount of culinary knowledge in the restaurant industry is staggering, and pop-ups give line cooks and other back of house workers—otherwise unseen by the casual, or even professional, observer of the food industry—the opportunity to shine.

Sarah Thompson is an industry veteran who’s currently heading up the charcuterie program at Bloomsday Café. She’s better known as the culinary force behind Tall Poppy Projects, which she runs alongside another industry veteran, Andy Donaldson.

“I want to focus on the Philadelphia community, because I really, really love it,” Thompson says. “I’d really like to be able to give away food for free, which I can’t afford to do right now, and I’d love to be able to partner with community organizers. I think for me it makes sense to stay a little more amorphous, a little more flexible.”

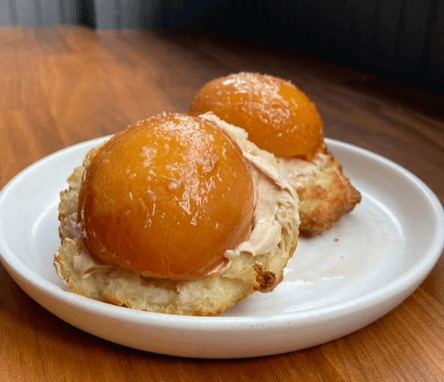

Among other things, Thompson trained in whole muscle charcuterie in New Zealand, but her pop-ups demonstrate her wider skillset. So far, she has hosted multiple events, most recently a handful of pop-ups at Bloomsday Café serving tall, burnished biscuits adorned with toppings like pork roll, pumpkin butter, or honey butter—all made by hand with ingredients from local producers.

Thompson says her current ambition isn’t to open a brick-and-mortar shop—after watching the devastation the coronavirus created for restaurants, she’d prefer to keep her overhead low and her business flexible in order to give back as much as possible.

“I want to focus on the Philadelphia community, because I really, really love it,” she says. “I’d really like to be able to give away food for free, which I can’t afford to do right now, and I’d love to be able to partner with community organizers. I think for me it makes sense to stay a little more amorphous, a little more flexible.”

The undefined nature of this type of pop-up is part of why this sector has strengthened during the pandemic—these types of businesses are flexible enough to adapt, and for many proprietors, it’s not their primary source of income. It’s a way for them to flex their creativity, become better cooks, and have something of their own, which is important in an industry where so much of the work is churning out someone else’s creation over and over. And it does pay: though Thompson is now back working part-time at Bloomsday Café, she says the pop-up is now part of how she supports herself.

There are also advantages for the host businesses. At Bloomsday, for example, chef/owner Kelsey Bush says the pop-ups have been good for business, bringing in new audiences and offering something different and exciting to their existing customers, and she expects that they will continue in some form even after Covid wanes.

![]() Since their reopening in the midst of coronavirus, the café is only open five days a week, so they’ve been happy to let pop-ups like Thompson’s use the space for free on days when it would otherwise be empty. Bloomsday has also hosted pop-ups on days they’re open, like a recent event with Jorge Ramirez, an employee of the café who cooked Pueblan food as a fundraiser benefiting the Greenfield School. Customers could preorder Ramirez’ food along with the regular café menu.

Since their reopening in the midst of coronavirus, the café is only open five days a week, so they’ve been happy to let pop-ups like Thompson’s use the space for free on days when it would otherwise be empty. Bloomsday has also hosted pop-ups on days they’re open, like a recent event with Jorge Ramirez, an employee of the café who cooked Pueblan food as a fundraiser benefiting the Greenfield School. Customers could preorder Ramirez’ food along with the regular café menu.

“It gives us new perspectives on new cuisines,” Bush says. “We get to cook it and taste it and it’s really fun and inspiring. In Sarah’s case, we also get to support our employees in her side hustle, which is important to me.”

Tall Poppy has also functioned like an incubator for Thompson’s work in the charcuterie program for Bloomsday. Take the pork roll, which she served at a recent pop-up. She had a little leftover, which she gave to Bloomsday. They used it in a brunch special that sold out quickly. Now, it’s a regular on their menu.

Nurturing diverse food entrepreneurs

For some chefs, pop-ups are a building block toward the goal of running a brick-and-mortar restaurant. Chance Anies of Tabachoy, a Filipino pop-up that he started as a cart parked outside Temple Medical School back in 2019, says part of the appeal of opening a brick-and-mortar location is the ability to support other pop-ups.

“Tabachoy has become successful because people shared their space with us,” he says. “I definitely wouldn’t be here without Lou from Sarvida and Perla or Kiki and Chris of Poi Dog. They’ve lifted so many other people up—I want a space that does the same.” As Anies works toward running a permanent space, he’s been serving dishes like lechon (roasted suckling pig) and chicken longganisa (fresh sweet and savory sausage) at places like Herman’s Coffee Bar and Mike’s BBQ. Teaming up with these businesses gives him a way to introduce diners to Filipino food, a relatively unfamiliar cuisine here in Philadelphia.

One seasoned restaurateur actually made the shift from brick and mortar to pop-up—or, rather, a pop up of pop ups—to try to scale up the collaborative potential of these microbusinesses.

When Ange Branca’s beloved Malaysian Saté Kampar closed last May because of Covid-related challenges and ongoing conflicts with their landlord, fans expected that she’d simply find a new space and continue turning out perfect grilled skewers and kaya toast. Instead, she launched Kampar Kitchen, a sort of ghost kitchen/food hall/culinary incubator that hosts a diverse crew of Philly’s pop-up chefs.

![]() “Even while we were running Saté Kampar, we had always been very involved in cultivating diversity in the restaurant space,” Branca says. In 2017, she started the Muhibbah Dinners, fundraising events where each course was prepared by a different chef—some big names and some lesser known—and highlighted a meaningful part of their culinary heritage, which they shared while guests ate.

“Even while we were running Saté Kampar, we had always been very involved in cultivating diversity in the restaurant space,” Branca says. In 2017, she started the Muhibbah Dinners, fundraising events where each course was prepared by a different chef—some big names and some lesser known—and highlighted a meaningful part of their culinary heritage, which they shared while guests ate.

At a dinner held in the spring of 2018, one course was prepared by the chefs behind then-burgeoning Pelago pop-up, a Filipino food company that eventually turned into Lalo, a permanent (though now-closed) stall in the Bourse Food Hall. Branca’s new project aims to support a similar trajectory.

“Kampar Kitchen is a way for us to marry the experience of running the restaurant with the idea behind those dinners: to bring in a new generation of chefs of all different backgrounds,” Branca says.

The business is run out of the Bok Building, where Branca rents out their now-empty event space. Branca has partnered with six chefs who run already established pop-ups in the city: Ruth Nakaar of Fudena (West African), Cote Tapia-Marmugi who cooks vegetarian Chilean food, Jacob Trinh of TrinhEats (Vietnamese-Chinese hybrid) John Paul Manansala of DapsCanCook (“Filipinx”), Joy Parham, who cooks soul food, and Chris Paul, who cooks Haitian food. Each week the chefs cook a meal one night a week (Branca also cooks the Malaysian specialties of Saté Kampar weekly).

“I don’t see Kampar Kitchen as a pop-up,” Branca says. “I see it as a second step after doing pop-ups, where the chefs have their food figured out and they know what they want to cook, but they’re not ready to do a brick-and-mortar—which isn’t what all chefs want. By the time they get to Kampar Kitchen, they’re running a business and we’re kind of helping them take that next step.”

Even if it is what they’re working towards, the jump from pop-up to permanent restaurant is enormous. Kampar Kitchen gives the chefs an opportunity to cook regularly (finding a space out of which to pop-up can be a limiting factor for many of these burgeoning businesses), and Branca takes care of many of the logistics: point of sale, ordering, delivery, advertising. That way, the cooks can focus on what they do best. The chefs pay a predetermined percentage of their sales back to Kampar Kitchen to help cover the overhead.

“This is how we come back,” Branca says. “We’ve seen so many independent restaurants close since Covid came to Philadelphia. For me, [this] is about supporting diversity and small business and the restaurant industry as a whole. It’s about rebuilding what we’ve lost in a way that is even stronger than before.”

One of her pop-up partners at Kampar Kitchen, Jacob Trinh, has worked in major restaurants like Momofuku in New York and Vernick Fish in Philadelphia, and found himself burned out before the pandemic hit.

“I was working 15 hour days, six or seven days a week,” Trinh says. “I took a pause from cooking for a while, and then coronavirus hit, and I started cooking a lot more at home and learning to enjoy it again.”

TrinhEats first sprang up as the name under which Trinh was selling his XO sauce, a super-savory, crunchy, spicy condiment from Hong Kong that Trinh makes with crabmeat, whitefish, tamari, sake, ginger, garlic, cured ham, dried shrimp, and more. He began selling it by the jar, but quickly began cooking full meals, all of which are anchored by the sauce.

“I kind of do a Vietnamese-Chinese blend of food,” Trinh says. “I’m still kind of figuring out what my style is and what I want to cook, and the pop-up gives me a lot of space to do that, which is amazing.”

For Trinh, partnering with Kampar Kitchen allowed him to retain the creativity, while skipping over some of the logistical challenges that pop-ups can present.

“It’s kind of like music,” he says. “If you’re an artist and you’re making music, you have no place to show your music other than online, so Ange kind of brings the stage so we can perform for the masses. They tell me how many boxes I’ve sold, and I just go from there, so it streamlines the process and allows me to focus on the food.”

Branca sees Kampar Kitchen as a way to recover and strengthen the now-precarious food scene in Philadelphia: one that’s highly varied, driven by passion, and welcoming to creativity.

“This is how we come back,” Branca says. “We’ve seen so many independent restaurants close since Covid came to Philadelphia, and the people who have fared the best are the larger, corporate restaurant groups who have the money to build out big outdoor dining setups and do other pivots. For me, Kampar Kitchen—and pop-ups more broadly—is about supporting diversity and small business and the restaurant industry as a whole. It’s about rebuilding what we’ve lost in a way that is even stronger than before.”

Header image, from left: Tall Poppy Projects' sausage, egg and cheese on a biscuit; Chance Aines of Tabachoy slicing lechon; TrinhEats' Banh Khot with fresh herbs and seafood XO sauce