In the 35 years since The Great Good Place: Cafes, Coffee Shops, Bookstores, Bars, Hair Salons, and Other Hangouts at the Heart of a Community was first published and 25 years since Bowling Alone was published, there has been a chorus of agreement that our communities need more “third places.”

Third places are those spots that one visits beyond home and work, and are the spaces where people from all different backgrounds come together. Public spaces, cafes, libraries, and yes, even bowling alleys — these are essential to helping people find connection beyond family and co-workers. Framed as the “civic commons” they also have the potential for people to see beyond their own political and religious beliefs, and as Carol Coletta put it in an interview a few months ago, they are essential to a functioning democracy. Local government and philanthropy have poured a lot of money into third spaces in the hope that supporting this social infrastructure can help us build more equitable cities even as our residential neighborhoods become more segregated and our workplaces more virtual.

While I endorse this line of thinking, I’ve grown increasingly concerned with the disappearance of second places — places where people work — as more people work remotely all or some of the time. Ever since Covid caused many people to work remotely, there has been much discussion about the benefits of remote or hybrid work — the control and flexibility over one’s schedule (particularly for caregivers), the reduction in the amount of time spent commuting — but relatively little concern about what the loss of office life means beyond its economic impact on building landlords, public transportation, and downtown businesses.

It’s possible that the coworking model has not been the right fit until now.

Research has shown that not only are more people spending more time at home since the pandemic, but they are exploring less of the cities they live in and mixing less with people from different economic classes. Many of us are getting less social interaction, particularly with “weak ties” — those casual acquaintances such as the neighbor who you run into at the bus stop or co-worker in a different department of your company. (And ironically, weak ties have been shown to be most beneficial to people in digital fields.)

Remote workers may even be missing out on the psychological benefits of the liminal space of commuting, which helps us transition between parts of the day. Whether or not we actually have the amenities befitting a 15-minute city, many of us are increasingly confined in our own neighborhoods unless we purposefully push ourselves out, and increasingly connect with people we already know there. It’s still unclear what the decline of second places will mean for many of us and for society over the long term.

A nation of entrepreneurs working from home or cafés

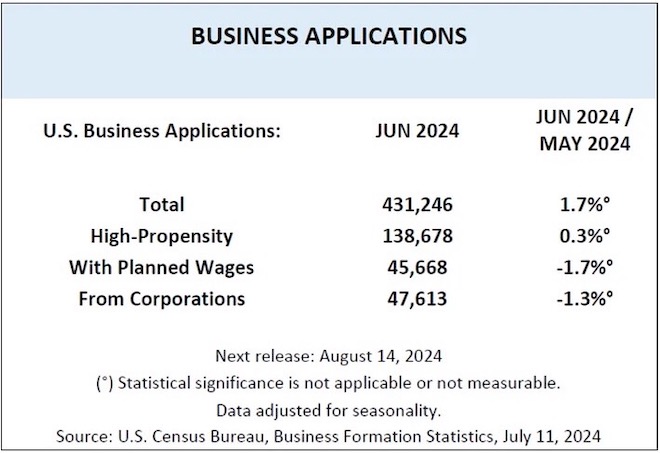

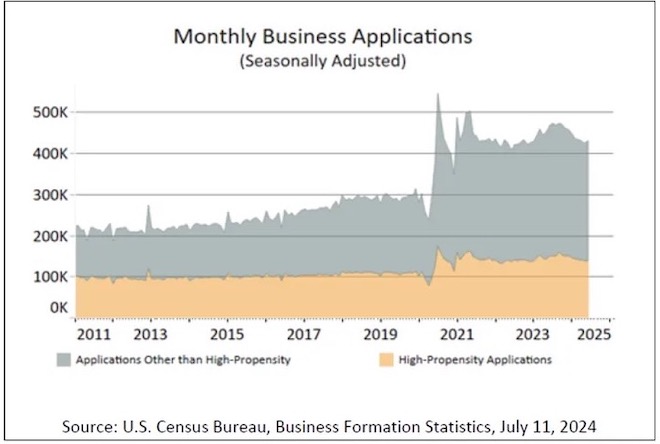

What’s strange is that at the same time that we are eliminating offices from our lives, more and more people are becoming entrepreneurs. Just look at this graph: small business applications — defined by the formation of an EIN — spiked after the pandemic.

While the pace of small business applications does seem to be slowing down a bit, the U.S. is still forming at least 100,000 more or 33 percent more businesses each month now than we were before the pandemic. It’s a significantly greater number of people who are either developing a serious side hustle or striking out on their own.

Undoubtedly, many of these businesses are screen-based ones rather than physical, brick-and-mortar businesses — indeed, some of those entrepreneurs may have left traditional jobs specifically to be their own bosses and to have complete flexibility over their schedules. But just because they are independent doesn’t mean that they don’t need second places, whether coworking spaces, offices, libraries, or coffee shops. In fact, 80 percent of small businesses are one-person companies — an inherently lonely situation — so it’s likely these new entrepreneurs could really benefit from the community of a second place.

Given that entrepreneurship continues to grow and office occupancy has plateaued, there is likely an unsatisfied demand for a new kind of second place.

The next era of coworking

Given the growth of entrepreneurs and the increase of people working remotely, why hasn’t coworking taken off? The implosion of WeWork has loomed large over the coworking world for the past five years. With WeWork emerging from bankruptcy with a new majority owner, Yardi, a real estate technology company, there’s potential that a slimmed-down WeWork might be able to more nimbly navigate coworking management. According to the Economist:

After the bankruptcy, Yardi wants to expand WeWork’s marketing to small businesses and to embrace technology used by hotels, such as real-time bookings. The company also hopes to launch an affiliate programme, in which it would team up with other coworking operators.

It’s possible that the coworking model has not been the right fit until now. Prior to the pandemic, most companies wanted the traditional coworking model; during the pandemic, companies were convinced that people would one day be back in the office five days a week. Now, as post-pandemic norms mature and leases come up, it seems likely that most companies will downsize, and there will be interest in high-quality coworking spaces, much like the flight to Class A office space. These bigger companies with more people using coworking space could provide the ballast needed to support these locations.

We need second places and co-working locations, but we also need to recognize that the kind of spaces … might need a subsidy of some kind to exist.

Still it seems like there is a fundamental business model nut that coworking has yet to crack. Many promising coworking companies have tried and failed. During the pandemic there were new concepts like Daybase, which opened in suburbs with the idea that suburbanites would want coworking closer to home. Others like The Wing, a women’s coworking space and social club in cities like Brooklyn, SF, and Boston, had also seemed to have a viable and unique concept, but then died.

It seems that coworking is too expensive, too far from home, and too restrictive for many remote workers and solo entrepreneurs. For these workers, the coffee shop offers many advantages over coworking.

Coffee shops are in the neighborhood, there’s no commitment in terms of hours or days, anyone can meet you there, and you can be as social or anonymous as you’d like. There’s so much demand for this kind of low-budget second place, people are willing to withstand bad music, loud blenders, and slow wifi for these advantages. The problem is that most cafes can’t make money off selling a table for $5 a day. The coffee shop coworking model is essentially a nonprofit one.

But given that it’s a second place, should local governments and philanthropies help support a model that is cheap enough and close for independent entrepreneurs, but more robust than a regular coffee shop?

We need to update the way cities support small business

Traditionally local commerce departments invest in retail, supporting pop-up shops and helping pay for commercial corridor improvements such as lighting, trash cans, and facade improvements. They help small businesses get loans and sometimes help larger businesses find office space or commercial real estate. But as we see the decline of second places for a growing proportion of our population, shouldn’t the same entities that care about the beneficial socialization and idea exchange of third places also consider supporting our second places as well?

There are a number of ways I could see this happening. Downtown business improvement districts could start thinking about becoming coffee shop and coworking operators themselves, or subsidizing them, and then using their connections to create programming and other benefits to engage people beyond a cup of coffee. For people who want to stay in their neighborhoods, local governments could support neighborhood coffee shops and coworking locations with the same kinds of grants that are provided to small businesses, perhaps having government workers host office hours there to help people figure out business taxes or loan applications.

Libraries have long struggled to develop coworking spaces — we should find out why these no-brainer locations aren’t creating spaces that offer a coffee shop feel. We need second places and coworking locations, but we also need to recognize that the kind of spaces that will serve most people are not profitable; they might need a subsidy of some kind to exist and are worthy of support just like third spaces.

Getting people out of their houses may soon become a need as urgent as getting people to use parks and libraries. We should support our country’s growing entrepreneurial spirit by developing second places that are affordable and vibrant by following the successful formula many cities have used to revitalize their public spaces and social infrastructure.

Diana Lind is a writer and urban policy specialist. This article was also published as part of her Substack newsletter, The New Urban Order. Sign up for the newsletter here.

![]() MORE FROM THE NEW URBAN ORDER

MORE FROM THE NEW URBAN ORDER