Last week, President Donald Trump came for our data. Executive orders to eliminate any DEI and climate change-related language from federal agency websites triggered a full scale removal of hundreds of pages on the U.S. government’s website — including Centers for Disease Control, National Institutes of Health, Department of Justice and the Environmental Protection Agency. (The CDC has since come back online with a note that says its “website is being modified to comply with President Trump’s Executive Orders.”)

Along with those pages disappeared thousands of pieces of information about Americans’ health, housing, income, climate, communities and other important data that informs state and local policies and business strategies around the country. The administration has not said if or when that data will be returned to the Internet — and, indeed, information on women’s health, LGBTQ issues and climate change may never see the light of day under Trump. Meanwhile, some media organizations and universities have saved most of the info, and researchers have archived a lot of the data, as well.

As the Association of Public Data Users put it in their statement: “The loss is not abstract: Among other things, data lost today helped people address urgent issues like teen mental health, bullying, and violence prevention. Put quite simply, today’s actions to remove taxpayer-funded data from the public domain impacts everyone in the United States, directly contradicts the mission of the federal statistical system, and robs the public of a benefit paid for by them.”

Thankfully, most of the deleted federal data exists at a Philadelphia benefit corporation called PolicyMap that collects private and public data and creates explanatory maps. On Tuesday, PolicyMap sent an email to its (panicked) customers assuring them that “Data that was recently removed by the federal government is, and will always be, available in PolicyMap.”

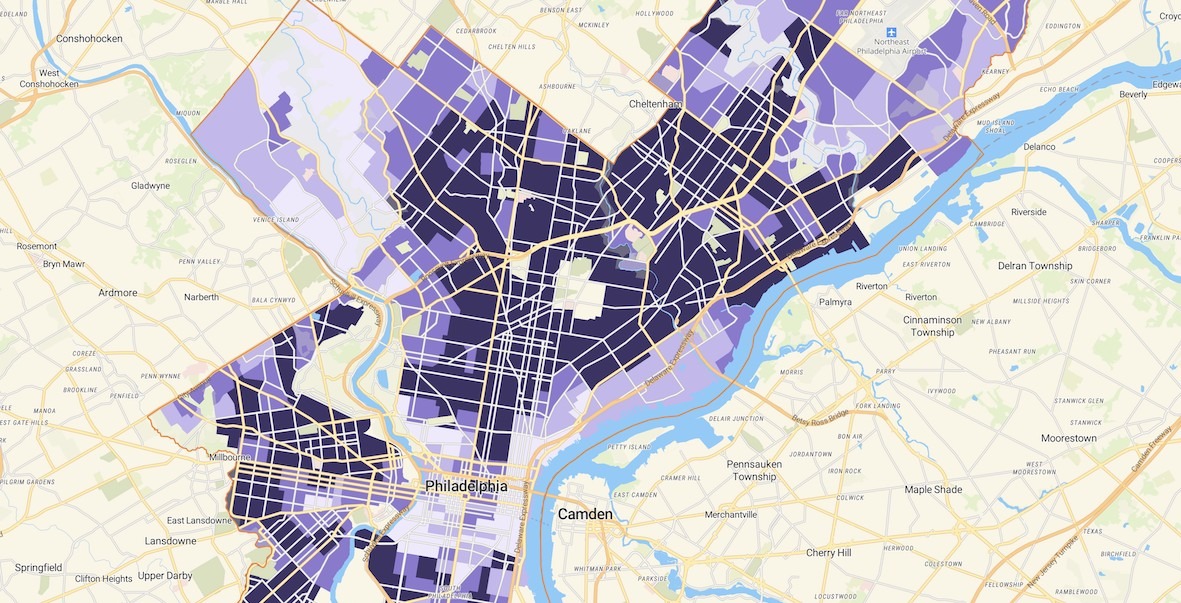

Here, for example, is an interactive PolicyMap rendition of the Social Vulnerability Index, which measures how susceptible communities are to disasters:

You can find a complete list of what PolicyMap has available here.

I caught up with PolicyMap founder and CEO Maggie McCullough to talk about the impact of the data’s disappearance — and why it’s not time to panic. This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Roxanne Patel Shepelavy: What does Policy Map do?

Maggie McCullough: We were first within the nonprofit Reinvestment Fund, and now we are our own small business, but our entire mission has been about helping people use data in order to make more strategic decisions about the communities in which they’re working. To do that, we spend a lot of time curating as much data as we can from all the public websites that are out there, and we also purchase private data where we think that there’s a gap so that people can really look at a neighborhood, a community, and get a really good picture of what’s going on in that place, whether it’s related to incomes or housing prices or poverty level or health conditions.

We take all that data, we store it in our warehouse, and we make it available in an online application so that you get all the data you need, all in one place. We remove a lot of the friction that exists from having to go to multiple different websites or different locations to secure the data, figure out how to map it, etc. We have almost 1,000 customers who use the data across industries for the same purpose, which is to better understand the markets in which they’re working and make more strategic decisions based on data that is accurate, relevant and timely.

“The loss is not abstract: Among other things, data lost today helped people address urgent issues like teen mental health, bullying, and violence prevention.” — American Association of Public Data Users

What kind of data are we talking about?

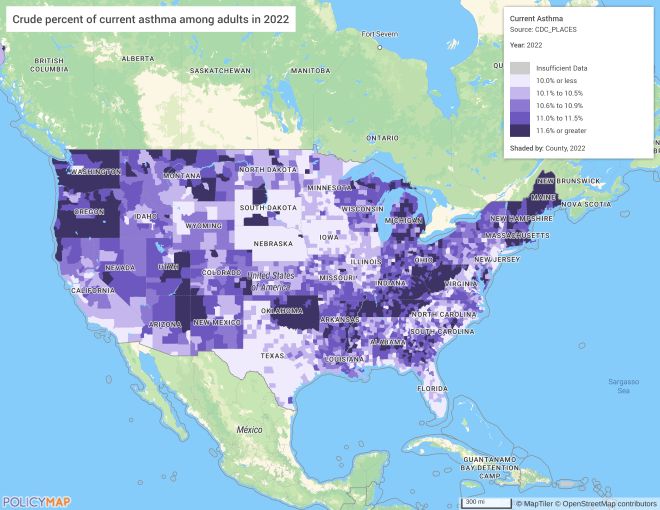

One is some of the data sets from the Centers for Disease Control, including one called CDC PLACES (Population Level Analysis and Community Estimates), and it gives us a lot of information about health conditions across the United States at a small geography, which is really helpful, because it’s one thing to know health conditions in the U.S. as a total, but it’s something else when you’re really looking at strategic interventions at a community level, to have that data at that smaller geography.

So, a hospital, for example, will use that data to better understand the kinds of conditions of the population that that hospital is serving and that helps them to also create community intervention plans, to work with nonprofits in the neighborhood around certain areas. If they see that diabetes is particularly high or asthma rates are particularly high, these are points of fact that they can use to then create plans to help reduce those conditions in their neighborhood.

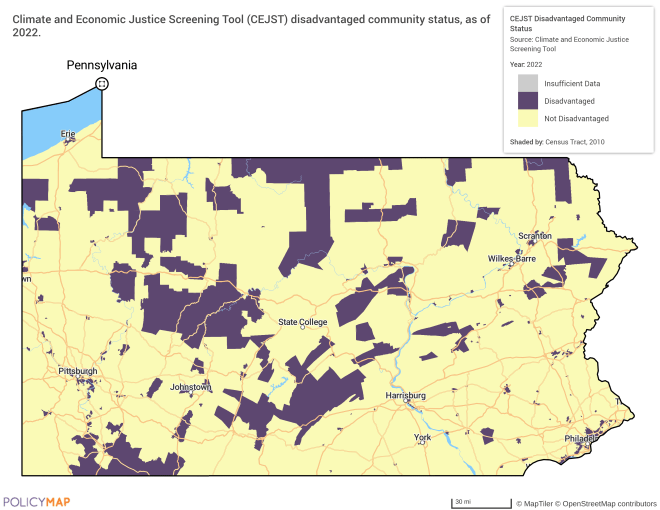

Another one that came down was Climate & Economic Justice Screening Tool (CEJST) which is filled with data that was on the White House website. That data is being used by entities across the country who are working on green development. Part of that green development stated that a certain percentage of their investments needed to positively impact communities that had been underserved in the past, low income communities. All of those related data sets have been removed, and so we don’t know whether that’s going to come back, or if any of those requirements are no longer going to be enforced.

You sent an email to your customers promising the data will “always” be available on Policy Map. Why?

So, obviously, timeliness becomes important when the federal government stops updating data. We sent out that email because there is, as I’m sure you’re aware, some panic that’s setting in among people about where they’re going to get the data. We have the latest that is currently available from the federal government within PolicyMap, so we wanted to let our users know that there’s no need to panic. We do have this data so that that solves that part of the question.

Then the question is, are these websites going to come back up from the federal government, and is the data going to continue to be updated? And we don’t know. We’ve heard what everybody else has heard — that a lot of web pages were taken down from the federal government to scrub them of certain terms like DEI and then they’ll come back up. But we don’t know.

We were getting calls from our customers wanting to know what was going on. We sent out that email to just assure everybody that we had the data and we’re going to always have it up there and it is all safe.

You said you have the latest available data — when is that from?

It really depends on the data source, but most data from the federal government gets updated annually. Much of the data was not scheduled to be updated until later this year. So hopefully we’ll see that. Some data sets, like unemployment, come out monthly, and there’s a number of data sets that come out on a more frequent basis. Those, as we understand, are still up.

So the annual data on Policy Map is as recent as it would be on the federal website?

Right.

Is it illegal to keep this data from the public?

It’s a good question, and I don’t know the answer to that. I don’t know if some data is Congressionally-mandated to be collected. Some data that the CDC collects is survey data that’s done at the state level. And then the states send their results of their survey data to the CDC, and then the CDC distributes it for the nation. So one of the questions is, you know, will CDC continue to do that? Will the survey still be conducted at the state level? Because a lot of that survey data is what allows for the estimation of what’s happening at those smaller geographies.

“We’ve heard what everybody else has heard — that a lot of web pages were taken down from the federal government to scrub them of certain terms like DEI and then they’ll come back up. But we don’t know.” — Maggie McCullough

Tracking data is one way to know if a policy works, right? That seems like it fits in with this administration’s push for “efficiency” in government.

Yes, it can really affect how states and communities are advocating for the types of help they need. In a world of limited resources, you have to think strategically about where you’re going to spend your money. Nonprofits have always been asked to make the case for why they need grant funding to do certain types of activities, and they rely on data to be able to accurately make that case, and then really, one of the most important pieces, is to track impact over time, to say, we made an investment in this area, and look how it improved, or we made this investment and nothing really happened as we thought, here’s what went wrong. I really do hope that the data is coming back. Maybe there’ll be a slight delay in the release of the next update, and that would be, in my mind, the best case scenario. And the worst case scenario is that it doesn’t come back, and then we have to figure out how we create these kinds of data sets.

Who are your customers?

We have a fair amount of customers that are universities, and we now sell into public libraries, so public library patrons can access Policy Map. We also have a large presence in the housing and housing finance space. So banks who are working on Community Reinvestment Act projects, housing finance agencies, who are dealing with housing-related investments in each of their states, a lot of local government housing and community development departments. And then healthcare has been a newer market that took off more because of Covid, when people recognized how conditions in neighborhoods impacted a community’s ability to deal with Covid. So we have health systems, some pharmaceutical companies, some hospitals, a lot of nonprofits that are also working in the health advocacy space, health equity, they use policy map as well.

They’re all doing the same thing, which is trying to figure out what is going on in the markets or the neighborhoods or the communities they serve, and where their dollars could be best used, how they should be best used to achieve whatever their goal is. In the healthcare system, everybody wants to reduce costs and improve health outcomes, so what kinds of community investments could best achieve that?

What can people do about this?

The American Association of Public Data Users suggests having people contact their Congresspeople to tell them how important it is that this data is available.

![]() MORE ON THE CONSEQUENCES OF THE 2024 ELECTION AND WHAT TO DO ABOUT IT

MORE ON THE CONSEQUENCES OF THE 2024 ELECTION AND WHAT TO DO ABOUT IT