Following the passage of the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan a year ago almost to the day, the Nowak Lab and New Localism Associates created an “Investment Playbook” tool to help cities maximize the fragmented flow of federal funds by strategically selecting geographies of opportunity and identifying and costing out concrete rescue and recovery projects within those geographies. This tool follows the simple maxim that “failing to plan is planning to fail”; federal investments may now be ample but only localities can design specific projects that are fit to place and geared for success.

The Investment Playbook approach allows cities to organize assets, build stakeholder consensus, and align investment. We have previously spotlighted the development of an Investment Playbook in Buffalo as one of the more ambitious community transformations we’ve seen in the United States. The co-investing strategy, organized through the Playbook, is already bringing together multiple sources of capital to implement a transformative vision for the East Side neighborhood. In addition to Buffalo, we worked with economic development leaders in El Paso to create an Investment Playbook for a major health corridor. This Playbook was part of our efforts with ACCELERATE El Paso, an Aspen Institute Latinos & Society Program (AILAS) initiative intended to spur an inclusive recovery for Latino businesses.

The Investment Playbook is now beginning to take hold as a common tool to use to ensure that the dizzying array of federal investments are placed in the service of local priorities. Beyond Buffalo and El Paso, for example, Erie, Pennsylvania and Greensboro, North Carolina have also prepared Playbooks in collaboration with New Localism Associates.

Significantly, a growing number of local leaders are seizing this moment and developing “Do It Yourself” (DIY) Investment Playbooks that build both on their existing work and the early models we’ve highlighted. We’ve observed at least three different communities that have further refined and elevated the Playbook concept: the Dayton Arcade District, the 52nd Street Corridor Initiative in West Philadelphia, and numerous projects spanning across city neighborhoods in Pittsburgh. As might be expected, these places have used the passage of time to provide more clarity on how to channel infrastructure projects for federal funding, curate more precise capital stacks, and respond to the disruptive dynamics that remain two years into the pandemic.

The Dayton Playbook

During 2018 and 2019, one of us visited Dayton several times (as part of an Opportunity Zones effort with Accelerator for America) to witness and assess the revitalization of an historic gem: the Dayton Arcade. As a “city in a city”, the Arcade was built by MJ Gibbons in 1903 and connected nine buildings across commercial, retail, and residential uses. As many historic downtowns experienced, the Arcade was shuttered in the 1990s as a result of sprawl and freeways, and only occasionally re-opened for holiday festivities. With the opportunity to revitalize this centerpiece of downtown and the surrounding area, a group of leading national developers worked closely with the city of Dayton and local anchor institutions to deliver the first phase of a broader transformation: a 400,000 square foot development in the south side of the complex (the South Arcade) that created the Arcade Innovation Hub along with retail and residential units.

Achieving success in the first phase was no small task; as we noted after our visit, the multiplicity and complexity of different forms of public, private and civic capital show how these projects, despite their transformative potential, are not for the faint of heart. The new realities of federal investment, however, raise the prospect that the next phase of multi-use revitalization will be easier to finance and deliver. To that end, key players in Dayton have created their own Investment Playbook, focusing on finishing the adaptive reuse of the Dayton Arcade itself and spurring revitalization in a broader Dayton Arcade District.

Dayton’s Playbook distinctly focuses on threading economic assets, underlying infrastructure, and the entrepreneurial ecosystem together as the pandemic reshapes industries, work places, and small businesses. It aims to enhance the tech and creative industries within the city’s downtown core.

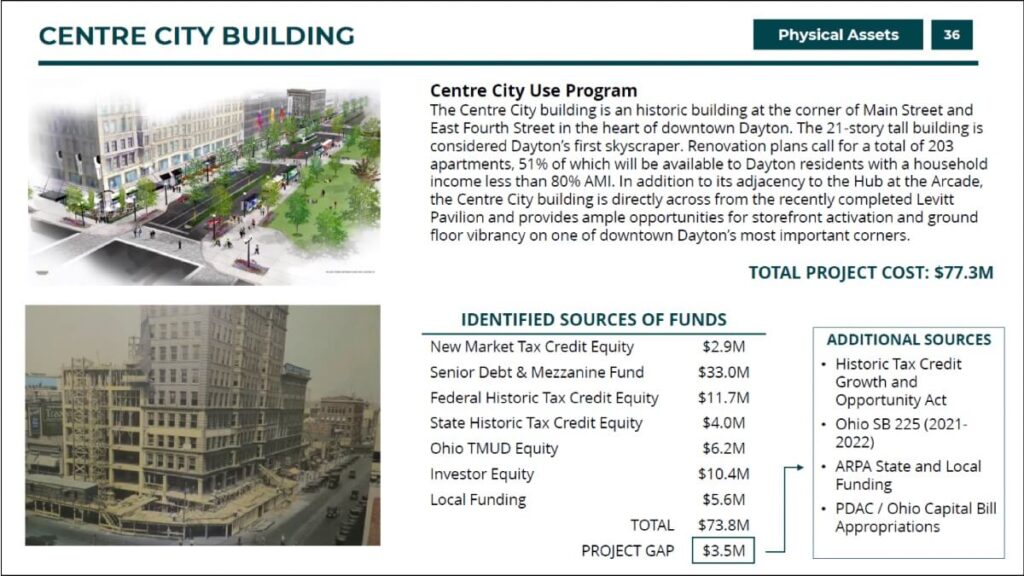

Focusing first on the Arcade District, the Playbook identifies four real estate development projects that expand the Innovation Hub; launch incubators that support the creation of an “art hub”; provide units for small businesses; and create affordable and market rate housing, which is mixed with hotel or commercial uses. Situating the District within the larger downtown core, the Playbook nicely demonstrates how surrounding developments will support targeted entrepreneurial efforts while infrastructure investments will create the placemaking and connectivity needed to make a corridor vibrant. Each of the four projects includes identified sources of funds and suggests potential sources that can fill gaps, as shown in the example below. These projects, in addition to the South Arcade, sum to around $225 million in total cost.

The West Philadelphia Playbook

Not too far from the Nowak Lab itself, the 52nd Street corridor in West Philadelphia serves as a significant cultural and economic asset within a neighborhood beset by high poverty and other indicators of social distress. Referred to as West Philadelphia’s “Black Main Street”, the corridor emerged in the mid twentieth century as an area with entrepreneurial and cultural opportunities for the African-American community.

In the following decades however, population declined and resulted in accompanying disinvestment. Furthermore, the rise of digital commerce and corporate retail continued to change the neighborhood; these trends were only further accelerated by the pandemic. Additionally, following the civil unrest after the death of George Floyd, Black community leaders and entrepreneurs are rightfully calling for the same kind of opportunities that 52nd Street was once able to provide.

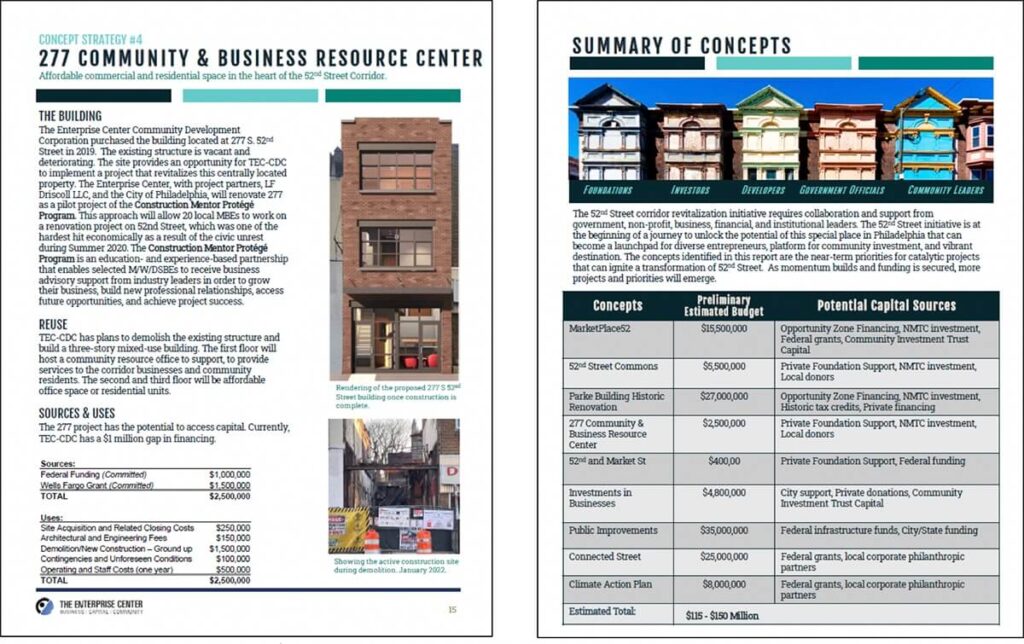

In an effort to restore 52nd Street as a lively hub for Black-owned and small businesses, The Enterprise Center Community Development Corporation—a place-based non-profit with West Philly roots—developed a Playbook for investors and funders to support shovel-ready and shovel-worthy investments that will sustain the forthcoming success of the corridor. The proposed concept focuses on creating an entrepreneurial hub for local-serving businesses, developing community “third spaces”, renovating an historic landmark, and creating affordable housing and commercial space. Potential sources and defined uses are outlined to show gaps where federal funding could be used.

Additionally, the Playbook includes supporting strategies that cohere with those mentioned: infrastructure improvements, street initiatives, and integration of climate-friendly technologies will help the corridor’s businesses sustain beyond pandemic-related and future challenges. For example, funding from the infrastructure bill can be used to retrofit real estate with energy efficient upgrades. These investments of $115-$150 million reflect the initial shovel-worthy investments that are a portion of the additional transformative investments needed.

The Pittsburgh Playbook

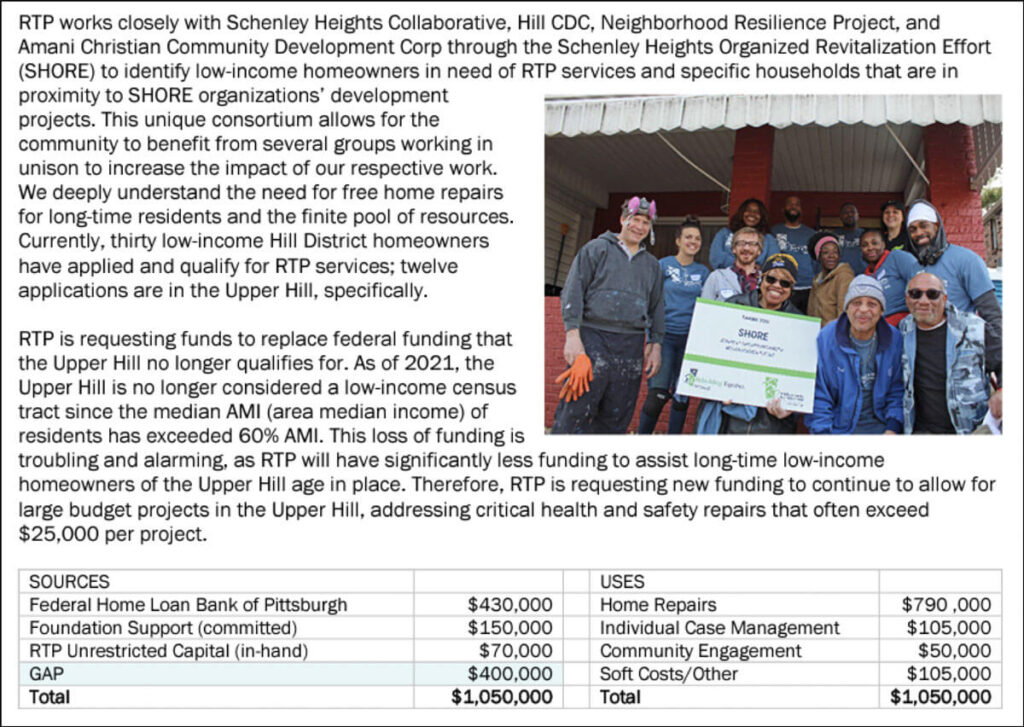

The Equitable Recovery Playbook was conceived by the Neighborhood Allies, a community development intermediary dedicated to “improving the social and physical infrastructures of Pittsburgh’s under-resourced and under-served communities.” This Playbook scales up the initial model, applying it to different areas in Pittsburgh, with project locations ranging from the Hill District, to Homewood and other neighborhoods. The other investable opportunities mentioned stand to benefit the entire region if they come to fruition. The investments represent around $34 million in total cost and are categorized into neighborhood development, economic opportunity, and community development.

Within these categories, Neighborhood Allies has carefully thought about the types of capital and stages that might apply to different categories. For example, “last dollar in” projects include those that are nearly-complete and need grant funding to close the final gap, while “catalytic capital” projects need early-stage equity to unlock access to more resources. Another category of projects, “emergent models”, directly responds to the challenges brought on by the pandemic, such as overcoming the digital divide. The community development investments in the Playbook focus largely on “aligning capital with strategy”, by establishing the Affordable Housing Revolving Loan Fund and the Equitable Growth Guarantee Fund.

While the physical scale of this Playbook is larger than the other two examples, the projects themselves strategically target smaller geographies that create transformative and holistic impact for their neighborhoods. For example, key investments that will preserve homes and local businesses focus on the Hill District, a historically African American neighborhood that can be poised to bring investment back into Black and Brown communities.

Next Moves for Investment Playbooks

The Investment Playbook tool is a work in progress. As evidenced here, the DIY Playbooks from Dayton, West Philly, and Pittsburgh both build on the initial template and take it further, given, in particular, the enactment of the bipartisan infrastructure bill.

Investment Playbooks could be created around place-based investment at the regional rather than the district or corridor scale. The tool, for example, emerged as the Build Back Better Regional Challenge (BBBRC) was playing out around the country. The Challenge has provided new wind into the formation of smart spending for transformative investment that’s rooted in advanced industry clusters that are naturally distributed across urban, metropolitan and regional geographies.

Unlocking the full potential of these regional clusters requires an array of investments in an array of projects: research centers of excellence, commercialization efforts, innovation districts, logistics improvements, brownfield remediation, historic building acquisition and renovation, just to name a few.

These separate projects naturally build on each other, even though they are often located in disparate parts of a city, metropolitan area or region. Identifying and displaying the projects through the Investment Playbook tool could help unveil the authentic geography of the cluster and reveal the ways in which investments in different places align with and reinforce each other.

Bruce Katz is the Founding Director of the Nowak Metro Finance Lab at Drexel University. Avanti Krovi is a Senior Research Fellow at the Nowak Lab.

The Citizen is one of 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and the city’s push towards economic justice. Follow the project @brokeinphilly.

![]() RELATED

RELATED

The Virus and the City: The Key To Inclusive Business Recovery

The Virus and the City: What $9.2 Billion in Rescue Funds Means for Philly

The Virus and the City: The State of American Competitiveness

The Virus and the City: A Better Way to Spend Covid Relief Funds

Header photo courtesy I, Mtruch / CC BY-SA