Why don’t we ever hear about black police officers? In the era of Black Lives Matter, far too often they are not included in the discussion over policing. As a result, a predominant media narrative has emerged pitting “Black Lives” against so-called “Blue Lives”—actually White Blue Lives—as if the two are mutually exclusive, and the public is compelled to choose one side or the other.

That narrative is on display in Milwaukee, where Sheriff David Clarke, who is African-American, has blamed the violent responses to police brutality in that city on “tribal behavior,” single mothers and “black cultural dysfunction.” Clarke has characterized #BlackLivesMatter as inciting violence against police. In his speech at the Republican National Convention, he slammed the movement, which he likened to a “collapse of the social order,” and which “violates the code of conduct we rely on. I call it anarchy.”

However, there is an alternate narrative: Black cops are uniquely positioned to address the problems of troubled police-community relations, of the killing of black people by law enforcement, and the need for reform in the system. After all, their presence in the department is a testament to social protest and to the civil rights struggle for inclusion, based on the argument that having officers of color on the beat, in the patrol cars and in the neighborhood is the only way to reform policing.

Yet, simultaneously, black officers experience conflicting loyalties to the community versus the department. Many face racial discrimination in their own departments, which helps explain why African-American police have their own organizations to look out for black interests and sometimes even their own unions, as in St. Louis, where the name of the African-American union—The Ethical Society of Police—hints at the internal chasm between the races. On the force, many report being subject to retaliation from their agency if they speak out against police corruption and abuse. And on the street, black officers are often victims of racial profiling, harassment and shootings from fellow officers.

Why it's difficult to have a diverse police forceVideo

“We come out of the era of white cops dominating the areas in which we grew up. And people thought hiring people of color in these police departments would change things,” said Rochelle Bilal—head of the Guardian Civic League, an organization that supports black officers. Bilal—who served as a Philadelphia police officer for 27 years before retiring—said she faced racism from her days at the police academy, and was called “Angela Davis” by her colleagues for not allowing white officers to commit misconduct in her presence.

“The community is justifiably angry, and I say justifiably because I know there are good police officers. But if good police officers don’t stand up it is very difficult to tell them apart,” said Sgt. De Lacy Davis, who served in the East Orange, N.J. police department for 20 years and founded Black Cops Against Police Brutality. Davis and Bilal helped to found the National Coalition of Law Enforcement Officers for Justice (NCLEOJ). “Well, you need to bring the good ones out, and those good ones are hard to find. Some of it is cowardice, some of it is desperation, some of it is, ‘I have a family to care for.’”

Davis points to the conflicts black officers face, citing what the West Indian psychoanalyst and revolutionary Frantz Fanon called Black Skin, White Mask. “There is an inherent conflict,” said Davis. “How do I walk around with black skin and survive in these systems that are white male dominated? Not only do you have to wear that mask, but you have to wear it in the police academy.”

In Philly—with its long history of police brutality from the Frank Rizzo years, and the MOVE bombing under Mayor Wilson Goode—black leadership of the police has not resulted in fair policies or equitable treatment for residents of color.

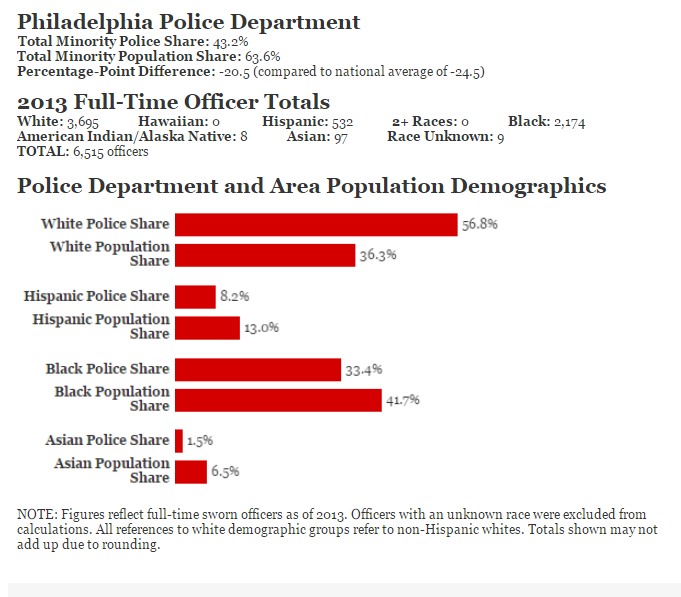

Our racial imbalance in policingCheat Sheet

Despite the department’s black leadership, stop-and-frisk has been a problem in Philadelphia for years. Black and Latino men who were victimized by the practice—including then-state representative and current Philadelphia Sheriff Jewell Williams—filed a class action suit against the city in 2010. Under Mayor Michael Nutter and Commissioner Charles Ramsey—both African-American—the PPD entered into a federal consent decree in 2011. Last year, the ACLU of Pennsylvania reported that “33 percent of all stops and 42 percent of all frisks were without reasonable suspicion.”

Internally, the black cop is often similarly targeted. “The black police officer is treated like hell in the police department, because he is trying to keep his head low,” Davis argues, noting the case of Cariol Horne, an ex- Buffalo police officer who was fired for stopping a white fellow officer from choking a handcuffed man. The offending officer—who punched Horne in the face, requiring her to replace her bridge—was forced to retire after choking and punching other fellow officers, and indicted for federal civil rights violations against black teens suspects. But Horne has been fighting for her pension for 10 years.

In New York, Officer Edwin Raymond resorted to recording NYPD officials in an attempt to reform the department. He became the lead plaintiff in a lawsuit brought by a dozen cops of color who claimed the NYPD forced them to meet racially discriminatory arrest quotas against blacks and Latinos. Other NYPD officers have received death threats and lost backup on duty from other cops for piercing the blue wall of silence.

And in Philadelphia, there is the case of Andre Boyer, a 17-year veteran who sued the police for racial discrimination and retaliation, claiming he was fired for being a whistleblower. Boyer then began posting details of alleged police misconduct on Facebook—including two supervisors accused of sexual assaults, and a cop suspended for calling his black boss “a banana-eating monkey”—and the Fraternal Order of Police sued him for defamation. And in 2008, a federal jury awarded three white officers $10 million for claims they faced retaliation after exposing police mistreatment of African-American colleagues and motorists.

Police and crime in PhiladelphiaRead More

Despite the many internal and external challenges facing law enforcement, there are solutions.

Davis believes there must be accountability for police officers and their appointed leaders, full whistleblower protection for cops who stick out their necks and speak out, and civilian oversight of the police, with communities determining the type of policing they want.

Community policing can also be an answer. For example, the White House recognized the Boston Police Department for strengthening relationships in the community, working with youth, and building trust in the neighborhoods. In addition, there is a police-community social justice task force to monitor police stops, and a priority placed on increasing diversity in the ranks of the department. Boston is also known for a non-militarized approach to de-escalating tensions, including having clergy or NAACP members present when police interact with protesters.

The Dallas police have received attention for their transparency, their work with at-risk youth, and Neighborhood Police Teams that get to know the community and are there as a part of the solution. Dallas cops undergo mandatory lethal force training every two months rather than every two years. Excessive force complaints, officer-involved shootings, crime and arrests have declined.

However, in communities where police have long been regarded as the enemy and seen as an occupying force, not everyone is convinced of the success of community policing, as skeptics and problems remain. Opting for window dressing, few departments have adopted all three elements of community policing: community partnerships, organizational transformation, and problem-solving. But those departments, like Boston and Dallas, that do enact all of these community policing pillars stand a better chance of undergoing the culture change within that can lead to justice on our streets. And that, Davis and Bilal and many other African-American police officers maintain, is what the goal ought to be: A change within police departments that ultimately does away with a cop culture that doesn’t serve the cause of justice.

Photo header: flickr>/Elvert Barnes