The last few weeks in Philadelphia have seen a dizzying array of bold plans for funding the Philadelphia School District, from Gov. Tom Wolf’s first budget proposal, to Mayor Nutter’s last, to once (and maybe future) mayoral hopeful Sam Katz’s in-depth analysis of the city’s needs. The funding issue is fraught politically, so it gets the bold headlines. But how the School District plans to spend the money it’s given may just be more important than what it spends.

While the dueling funding plans garnered the headlines, Superintendent Bill Hite released his Action Plan 3.0, which comprehensively lays out just what the District would do with all of its newfound wealth. The plan will not satisfy everyone—yes, there will be charters; no, there will not be dozens—but it has ambitions to appeal to school advocates all along the spectrum—innovation, fiscal, curriculum, community. “I look at this as a plan for the whole city,” says Ami Patel Hopkins, Vice President of Teaching, Learning and Innovation at the Philadelphia Education Fund who previously worked in the Mayor’s Office of Education. “It considers the wide variety of schools that exist within the system, and makes clear that the District is driving to get to equal options for all students. That’s important for everyone in the city to understand.”

In the coming weeks, The Citizen will delve into some of Hite’s ideas in greater detail. (We’ve already addressed some, including the District’s innovative high schools and the success of the Renaissance schools). For now, these are the highlights that showcase a new, or refined, approach to educating Philly’s schoolchildren:

School autonomy. For the first time, the District is promising to give certain principals, at certain schools, a lump sum of money for the year, the way it does with charter schools. This is huge. It acknowledges two things: That the District no longer has the personnel to micromanage all of its more than 200 schools; and that good principals have become much more than just instructional leaders. “The role of principal has changed considerably in the last couple of years,” says Danielle Wolfe, Senior Analyst of the Center for High Impact Philanthropy, and policy committee co-chair for PhillyCORE leaders, a consortium of young Philly educators. “Now they are also crisis managers, administrators, fundraisers and community organizers. They are capable of making decisions based on the needs of their schools.” The District will still have to honor contracts, so it doesn’t mean principals will be able to hire and fire at will, the way non-union charter schools can. But it may mean they can use their allocated funds to buy more computers, or more arts programming, or more social services—the way charter schools do. The criteria for which schools would qualify is not set yet, so there is no sense of how widespread the autonomy will go. Schools like Meredith and Masterman are bound to be on the list. But what about schools with lower test scores that show great promise under their current leadership? Don’t know. The breadth of this flexibility seems to depend on another bold, if less flashy-sounding, proposal:

A fee-for-service model for non-academic purposes. It’s not entirely clear how this would work, but the idea seems to be that the District would let schools decide which non-academic services they receive from the central office—like food, transportation and maintenance—rather than sign citywide contracts with vendors for services that not every school needs or wants. The District has also proposed offering these services to non-District schools. It’s another sign of a willingness to modernize the District’s bureaucracy, and could be a cost-saver and revenue-generator—though how much is unclear. Like with the autonomy piece, this won’t happen right away. The Action Plan—which mentions a similar program in Denver—says it will start with a pilot program “over time.”

There may be more charters. But not so much in the greater Center City area, and preferably Renaissance, which are neighborhood publics turned over to outside organizations to run, but that are less costly to the District than stand-alone charters. Hite emphasizes throughout the Action Plan that the District will be what he calls “a great charter school authorizer.” This means developing stricter criteria for judging both new and existing charters, including for the first time issuing annual School Progress Reports for charters to allow “apples-to-apples comparisons between schools serving similar populations.” Theoretically, this could make it easier to close charters that underperform. The plan also calls for a renewed effort to ensure charter school funding aligns with the actual enrollment and needs of students in each charter school—something else for which charter opponents have long advocated.

Revive the idea of Turnarounds. Hite’s plan calls for a wholesale reorganization of the District into “networks,” including a Turnaround Network for the lowest-performing schools, which he says “requires deep expertise, experience, and sustained focus.” This network will include charters, Renaissance charters and District-run schools that hearken back to the Promise Academies launched under Arlene Ackerman—which were effectively scuttled through defunding after the first year.

Teachers matter—yes, even at a time when the District and teachers’ union are sparring over the SRC’s attempt to nullify the city’s teacher contracts. The Action Plan stresses that the District will bump up efforts to hire the most qualified candidates, empower teachers to become school leaders, and help them become better teachers through training and by supporting existing networks of teachers. “Teachers are the change agents for the Philadelphia School District,” says Hopkins, who says the Education Fund pushed the District to ensure teacher collaboration was part of the plan. “They create a culture of teaching and learning within a school. Equipping and empowering them is really important.”

Innovation matters—yes, even when times are tough. Hite fielded some criticism last year when he announced the opening of three small new innovative high schools (which launched this fall) at a time when many existing schools could barely afford paper. His Action Plan this year plan doesn’t call for any new schools, but does create an “Innovation Network” to explore “evidence-based personalized learning models” the District might pilot in some schools and use to open new ones in the future. Several points in the plan touch on experimenting with new ideas in teaching and running schools—an acknowledgement that the public school system cannot be the same unmovable entity it has been for decades. Unfortunately, the District’s Office of School Improvement and Innovation currently has only one staffer—Executive Director Ryan Stewart—which may make this difficult to actually implement.

Community matters. The District has not followed some other cities in creating widespread community school models, which bring neighborhood supports directly into the same building, as New York and Cincinnati have. But Hite this year is inviting far more community involvement than under previous plans. In some ways, this is playing catch-up: Neighborhood “friends of” groups have erupted all over the city to help their local schools with fundraising, supplies, volunteers and capital projects. This Action Plan is the District’s way of formally acknowledging something that’s already happening—and opening the doors to nonprofits and other community groups that have sometimes found it hard to work with the District.

Testing is still the main benchmark. After all the talk in Action Plan 3.0 of innovation and flexibility and community involvement comes what is, in most respects, the least interesting page in the 56-page document: A list of the ways in which the District will track its progress. Almost all the measurements are related to how well students score on standardized tests like PSSAs and Keystones. “My desire for the District is to start thinking outside the box about how we can evaluate outcomes differently than we do,” says Wolfe. “For example, there is a lot of talk in the plan about meeting the socio-emotional needs of students—but there is no mention of an assessment to measure that. It’s challenging, but it’s something I hope we can start to address.”

Still, even here, the plan’s ambition is apparent: The goals are 100 percent graduation rate, college or career ready; 100 percent of 8 year olds reading at grade level; 100 percent of schools with great principals and teachers; and 100 percent of needed funding. Is this possible? “Realistically, we can’t meet all those goals, even if we get all the money that’s being proposed,” says Hopkins. “But if you only set goals you know you can make, you’re not being ambitious. These are expectations the District is moving towards, and it’s important for the city as a whole to know that this is where the District wants to be.”

This first ran on The Citizen on 3.16.15

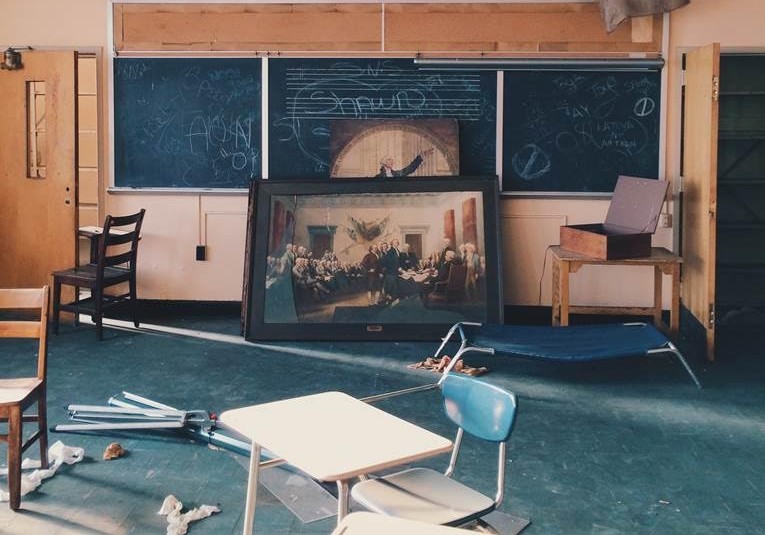

Header photo: Austinxc04