When Krystal Bryant graduated from William Penn High School 20 years ago, her academics earned her plenty of scholarships to college. But juggling college while raising two infants didn’t work. Instead, Bryant was on welfare and working as a cashier at Strawbridge’s, looking to make the best out of a difficult situation.

Then, one day, she came home to a pamphlet in her mailbox from the The Opportunities Industrialization Center (OIC), the North Philly jobs training program started by Rev. Leon Sullivan in 1964. She signed up for culinary training, secured internships and mentors through OIC.

Today, Bryant is the Executive Chef at Sonesta Hotel, the first African American female to hold that position in Philadelphia. “OIC was a turning point in my life,” Bryant said recently. “They gave me everything I needed to get my foot into the door. [The OIC] and my determination, that’s what made me successful.”

Hospitality has long been OIC’s main focus, because there have always been hospitality jobs in Philadelphia that are relatively easy to secure—if not always particularly lucrative. But now the jobs training program has set its sights on an industry with real potential for jobs that can sustain people’s lives in a long-term career: Banking.

“Maybe in six months to a year I could get promoted through the career pathway in banking,” says Tiffany Lassiter. “Then I’ll be making salary without a degree. That’s wonderful.”

Through a partnership with Seattle-based Bankwork$, OIC this fall launched an eight week program to teach underprivileged Philadelphians the ins and outs of the banking industry, including the soft and hard skills needed for jobs as bank tellers, customer service reps and personal bankers. Along with classwork, the program included internships and—through partnerships with local banks—the opportunity to apply for actual jobs after graduation.

“Banking is a field that is profitable,” says Rev. Kevin Johnson, President and CEO of OIC. “It is a career that allows people to have an upward trajectory, even for individuals that have a high school diploma or GED. Who knows what they’ll become from there.”

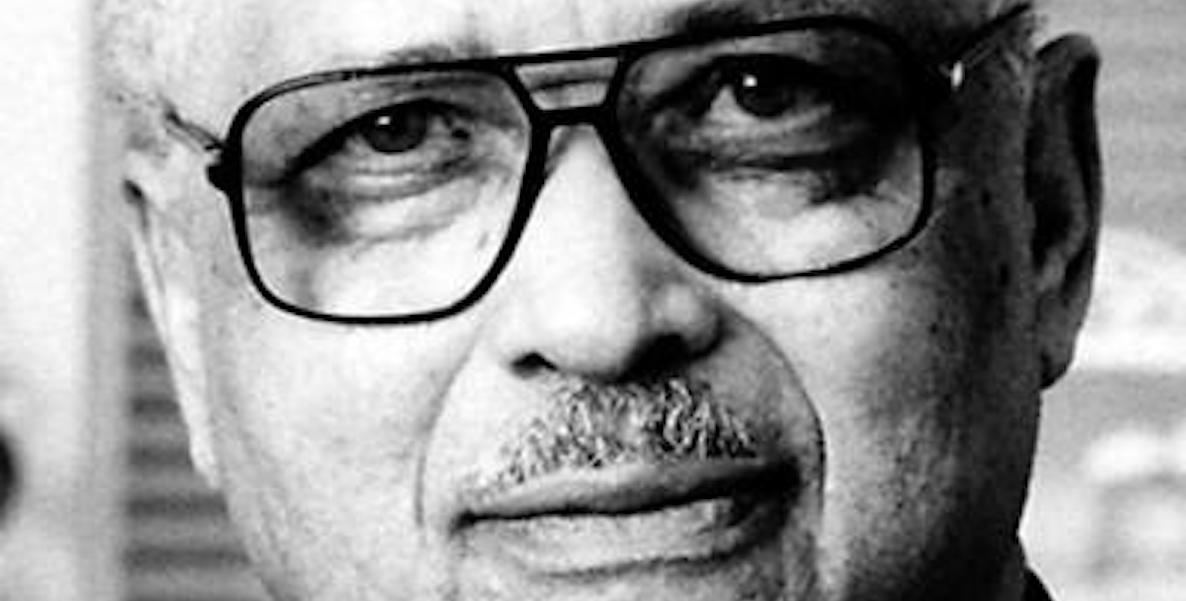

Philadelphia legend Reverend Dr. Leon Sullivan renovated an abandoned jail house in North Philadelphia into the first training center of the OIC in 1964, with a mission to combat unemployment in the African American community. Sullivan was a pillar of activism, organizing boycotts of companies—like Tasty Baking, Sun Oil and Gulf—that discriminated against black Philadelphians, coining the term “Don’t buy where you don’t work.” The boycotts factored in to several thousand jobs opening up for the community.

Sullivan’s impact and activism reached as far as South Africa, where to this day, American corporations that do business abide by the “Sullivan Principles,” which lay out ways that corporations need to have a social responsibility to the communities in which they operate.

Back home in Philly, Sullivan saw employment as the way to lasting economic development and empowerment, and the lack of training as the roadblock to that opportunity.

That is still the case today. One out of four people are unemployed in the zip codes surrounding the OIC, and too often area high schools don’t teach the skills many need for the jobs that people can live on. Like Sullivan, Johnson says OIC’s mission is to “eliminate poverty, unemployment and illiteracy” by filling in that gap.

“We have a legacy,” says Johnson. “People trust us to help them get a job. There are so many people who share with me that ‘OIC helped me get a job. OIC helped my children get a job.’ We’re trying to build upon that foundation and continue to help people help themselves.”

Johnson started at OIC in 2015, shortly after resigning as pastor of legendary Bright Hope Baptist Church amidst controversy over his financial management, leadership and involvement in politics. He went on to form Dare to Imagine Church, Inc, in Mt. Airy, where he is currently the pastor of a growing congregation.

He took the reins at OIC when the organization was in dire straits. Revenue at that point had shrunk by half, to about $1.8 million, and student enrollment in the hospitality program was barely 50. Under Johnson’s leadership, in addition to Bankwork$, the OIC has started operating the Workforce Academy, a GED program in partnership with the School District of Philadelphia, and a reentry training program through the U.S department of Labor. The OIC boasts revenue last year exceeding well over $6 million, from contracts to run the additional programs, grants and donations.

The Bankwork$ partnership creates the equivalent of the OIC’s Fox School of Business, potentially bringing graduates starting incomes up to $35,000 a year. Since its inception, the program has graduated over 2,000 BankWork$ students across the country, with more than 1,400 placed in banking positions across eight different cities.

As it has since its inception, OIC functions as a crash course trade school or job readiness class. The 12 to 16 week programs train for entry level jobs in hospitality and information technology, at a price that Bryant describes as the cost of a knife kit. The Bankwork$ program was free for all those accepted.

But OIC recognizes that education alone isn’t enough, particularly with its mostly black clientele. A 2004 study found that traditionally black sounding names got 50 percent fewer callbacks for job interviews than white ones. OIC counters that with their partnerships with institutions like Wells Fargo, Citizens Bank or the American Hotel and Lodging Educational Institute. As a result, Johnson says, OIC has an 80 percent job placement rate.

![]() When the OIC started out, it was like a university with only one department—hospitality. Over the years, it has added course tracks like culinary arts programs and guest service programs. But despite Bryant’s success, the typical graduate of the hospitality program makes around $22,000 or $23,000 a year, according to Johnson.

When the OIC started out, it was like a university with only one department—hospitality. Over the years, it has added course tracks like culinary arts programs and guest service programs. But despite Bryant’s success, the typical graduate of the hospitality program makes around $22,000 or $23,000 a year, according to Johnson.

The Bankwork$ partnership creates the equivalent of the OIC’s Fox School of Business, potentially bringing graduates starting incomes up to $35,000 a year. Since its inception, the program has graduated over 2,000 BankWork$ students across the country, with more than 1,400 placed in banking positions across eight different cities. The program specifically targets young adults from underserved neighborhoods who otherwise may not have the opportunity to seek a career in the banking industry.

The national expansion is being sponsored by three partner banks—Bank of America, U.S. Bank and Wells Fargo—along with many local banks who support the program by hiring their graduates and sponsoring the local vocational training organizations.

Philadelphia competed with cities like New York and Boston to become the first Northeast U.S. location of Bankwork$, which has branches in 10 cities. Johnson says the history and infrastructure of OIC, as well as the advocacy of Council President Darrell Clarke and former city councilman Wilson Goode Jr. helped the city win its bid for the program.

“When you look across the landscape of Philadelphia and the diffrent workforce development available here, there were none that focused specifically on the financial services industry”, says Wells Fargo community relations vice president Stephen Briggs. That made it the perfect fit for what Bankwork$ had to offer.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, financial activities added an average of about 15,000 jobs a month in 2016, a number 2017 was expected to match. Overall, employment in banking occupations is projected to grow 9 percent from 2016 to 2026, adding about 750,400 in new jobs.

The first OIC class of Bankwork$ graduated 13 students in December, including Tiffany Lassiter, a 30-year-old mother of four, who saw an ad for the program in the metro and saw it as an opportunity for her to explore a banking career. Determined not to miss the deadline, she cut the ad out of the metro and called biweekly about the program for three months.

![]() Lassiter and her fellow graduates first had to pass a basic math and writing assessment, then a round of interviews with the writer of Bankwork$ curriculum, Lisa Meadows, and the OIC instructor for the program, Shantelle Faison. Out of around 100 that applied, only 13 made it through to fill the max 25 seats for the 8 week program. “You could have sworn I hit the lottery,” says Lassiter.

Lassiter and her fellow graduates first had to pass a basic math and writing assessment, then a round of interviews with the writer of Bankwork$ curriculum, Lisa Meadows, and the OIC instructor for the program, Shantelle Faison. Out of around 100 that applied, only 13 made it through to fill the max 25 seats for the 8 week program. “You could have sworn I hit the lottery,” says Lassiter.

Over the eight weeks, students received practical application training such as mock transactions, balance sheets and also financial literacy with material on banking regulations and credit. Lassiter is now fluent in “bank-a-lese.” After the graduation, the 13 graduates interviewed with local partnering banks like Citizens Bank and Santander—and all of them got jobs.

“Maybe in six months to a year I could get promoted through the career pathway in banking,” says Lassiter. Her eyes light up at the thought of the future. “Then I’ll be making salary without a degree. That’s wonderful.”