I was recently asked by Architectural Record to write a case for preserving the Roundhouse in Philadelphia. When I said I couldn’t actually write that case, they allowed me to give a more complicated argument instead. (NB: I did not write the headline.)

The Roundhouse was the site of the former Philadelphia police headquarters, officially vacated in 2022. As I write in the Record piece, the building has a good deal of historic value:

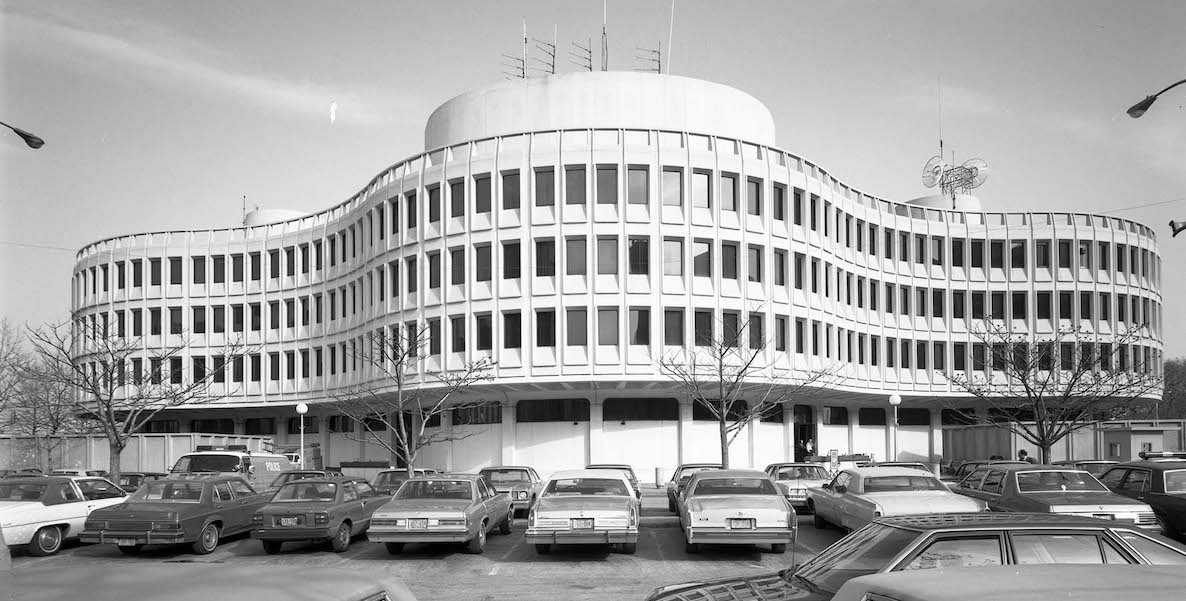

Its design, which resembles binoculars — or, perhaps, handcuffs — when viewed from above, won GBQC the AIA’s Gold Medal Award for Best Philadelphia Architecture in 1963. The structure pioneered the use of architecturally expressive precast concrete in the United States, incorporating roughly 1,000 precast units in its facade. It stands as a prime example of the midcentury Philadelphia school, which included works by Louis Kahn, Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, and notable architect, educator, and GBQC cofounder Robert Geddes.

The building’s legacy is decidedly mixed — built with great intentions for reform, it came to be synonymous with racist and violent police tactics. While structurally sound and carrying architectural bona fides, the city recently denied it a place on Philadelphia’s Register of Historic Places. Its future is therefore uncertain:

While this move does not guarantee demolition of the 125,000-square-foot structure, it opens the door to it. The building sits adjacent to a 50,000-square-foot parking lot on a city-owned 2.7 acre lot site ripe for redevelopment.

I agree that preservation is an important tool. As I’ve walked around San Francisco the past 24 hours, the historic architecture is really astounding and so essential to the city’s story and meaning.

And yet, preservation often complicates an already slow and difficult development process. As cities feel increasing urgency to build new housing and amenities, they have to figure out how and when to incorporate preservation into a growing city.

In Philadelphia, several big historic buildings have recently ended up sitting vacant:

Philadelphia does not have a great record of quickly turning historic buildings into new developments. A Beaux-Arts building by John Torrey Windrim in one of the most choice parts of the city has gone unused for a decade since its designation on the federal Register of Historic Places. A 1961 futuristic saucer-shaped visitors center in famed LOVE Park has sat empty since a multi-million dollar renovation was completed in 2019; the city’s RFP for a restaurant tenant in the space landed not a single response. And there’s been no movement on the site of a historically protected 1959 building that served as a city health clinic, even though it was sold in 2019.

For the record, I’m glad these structures were preserved. But I’m really dismayed that they’re going unused.

I also want to say that preservation and development do sometimes go hand in hand.

One can look to 2300 Market Street where KieranTimberlake is building a life sciences building on top of two older buildings within a historic district. The developer, Lubert Adler, is one of the city’s most experienced with dealing with historic properties, and the project went from proposal to completion in a reasonable five-year time frame. We need more examples like this to show that new development with historic buildings does not have to mean a 10-year penalty and an overly complicated capital stack.

But when should the importance of preservation outweigh other concerns, like time and taxpayer money? Particularly, in cities like Philadelphia, which are in need of all the positives — people, housing, tax revenue, jobs — that new development can bring.

A recent piece by Ryan Puzycki puts it this way in his City of Yes newsletter:

Forced historic landmarking is not a preservation tool but an anti-development tool, one that seeks to ossify the shape of the past in defiance of the needs of the future.

I am all for preserving historic buildings—but not in blithe evasion of the real financial and opportunity costs of doing so, not when it is forced, and certainly not ex post facto. If cities wish to incentivize the voluntary preservation of certain structures, they should also consider the extent to which such incentives end up being tax breaks for the wealthy who can afford the cost of maintaining them—or whether it’s worth spending taxpayer funds to appease aesthetic preferences while doing nothing to address whether people can afford to live in a museum city.

Ideally the city would be able to both preserve the Roundhouse and also build a new neighborhood on its multi-acre site. But between the two, I’d take the new neighborhood.

The situation at the Roundhouse site feels urgent to me: for decades, this area — at the perfect nexus of transit, a family-friendly park, and job centers — has languished, lacking ground-level retail, housing, and infill development that would rid the neighborhood of its overwhelming number of parking lots.

If the City of Philadelphia puts out an RFP for the Roundhouse site, it could see what a full range of future development opportunities could look like. I am certain some developers would propose keeping the Roundhouse as part of their plan. The city then could evaluate the proposals based on their social, economic, and environmental merits – not only preservation.

Diana Lind is a writer and urban policy specialist. This article was also published as part of her Substack newsletter, The New Urban Order. Sign up for the newsletter here.

![]() MORE FROM THE NEW URBAN ORDER

MORE FROM THE NEW URBAN ORDER