Last month, two days before we learned that Philly made the first cut in the Amazon HQ2 sweepstakes and three weeks before the Eagles became, as Chris Long has proclaimed, “the center of the football universe,” Citizen Chairman Jeremy Nowak and Brookings Institution scholar Bruce Katz kicked off the publicity tour for their new book, The New Localism: How Cities Can Thrive In The Age of Populism.

Be Part of the Solution

Become a Citizen member.At a crowded Center City event, both men—who have forgotten more about cities than you or I will ever know—zeroed in on that which sets successfully rebranded cities apart: Horizontal, rather than vertical, leadership. In, for example, Pittsburgh and Indianapolis, leadership hasn’t flowed from the political elite down; instead, academic, philanthropic, civic and business leaders all sat at the problem-solving table together and mapped out discreet strategies that have resurrected once-moribund city centers.

![]()

Afterwards, I asked Katz just how much storytelling had to do with such successful rebranding—and if our lack of it holds Philadelphia back. “Storytelling is essential,” he said. “Philadelphia is known around the world. And that, I think, has led to complacency. Storytelling comes from a sense of urgency. Pittsburgh and Indianapolis had to step up for different reasons—the steel industry collapsed in Pittsburgh, and the city core collapsed in Indianapolis. So the one thing I would say for Philadelphia, as a platform for telling its story, would be to feel the urgency.”

Have we, though? During the Eagles’ magical run, it was stunning to see just how much of the national press focused on old archetypes of our city: Booing Santa. Greased light poles. Crowd hooliganism (even if our crowd committed less vandalism than other celebrating cities). Every game, there was the predictable video of cheesesteaks sizzling on hot grills.

We are complicit in a widespread one-dimensional perception of our city, because we don’t unabashedly tell others who we are. And make no mistake: It’s a perception of us that predominates beyond sports, too.

We are complicit in a widespread one-dimensional perception of our city, because we don’t unabashedly tell others who we are. And make no mistake: It’s a perception of us that predominates beyond sports, too. Last June, just after Philly chefs and restaurateurs swept the prestigious James Beard culinary awards, a friend of mine flew into Philadelphia International Airport where she was greeted by a video on the way to baggage claim urging her to partake in our local delicacies: “Cheesesteaks, soft pretzels, and scrapple.”

![]() Visit Philly has done groundbreaking promotional work for the city over the years, including making Philadelphia the most gay-friendly city on the map. But in 2016, it unveiled an ad for the city featuring a giant Ben Franklin and a giant cheesesteak duking it out on our streets; the intention was to get beyond the familiar tropes, but it was too clever by half and showed, instead, that we’re still defining ourselves in relation to our timeworn cliches:

Visit Philly has done groundbreaking promotional work for the city over the years, including making Philadelphia the most gay-friendly city on the map. But in 2016, it unveiled an ad for the city featuring a giant Ben Franklin and a giant cheesesteak duking it out on our streets; the intention was to get beyond the familiar tropes, but it was too clever by half and showed, instead, that we’re still defining ourselves in relation to our timeworn cliches:

While the Eagles went on their historic run, I heard from friends across the country, some whom I haven’t talked to in years. Without fail, none knew that we’re the nation’s leading destination for millennials looking to making their mark, or that researchers like Dr. Carl June at the University of Pennsylvania are making great strides in curing cancer, or that Philadelphia is ground zero in the social entrepreneurship movement, with more B Corps per capita than any other city.

The Philadelphia that local writer Jim Saksa wrote about on Salon leading up to the Super Bowl is still a well-kept secret: “More and more Philly residents don’t see themselves in Rocky’s story. Philadelphians are, increasingly, middle-class kids who came to the city for college and never left. They’re not resilient survivors. They’re medical researchers, Comcast employees, and a cadre of relatively well-off professionals who moved to Philly because it has three-fourths of what New York has to offer at half the price.They haven’t eked out an existence on the mean streets of West Philly. They’ve restored Italianate manses on the tree-lined streets of University City.”

How, then, to tell a new Philadelphia story? After all, the rule of thumb in the urban advertising space is that 86 percent of branded ad campaigns for cities actually fail.

Why? “Because they feel like advertising,” says creative director Dan Shepelavy, formerly of The Brownstein Group ad agency which—full disclosure—designed this site. (He is also married to The Citizen’s executive editor.) “People are really skeptical. They’re being sold something all day long, and advertising is a very crowded field. Good luck trying to muscle out Nike. The trick is to treat it like a communications campaign with a unique voice that cuts through the noise. And to do the rigor of getting beyond a list of attributes and coming up with a narrative idea.”

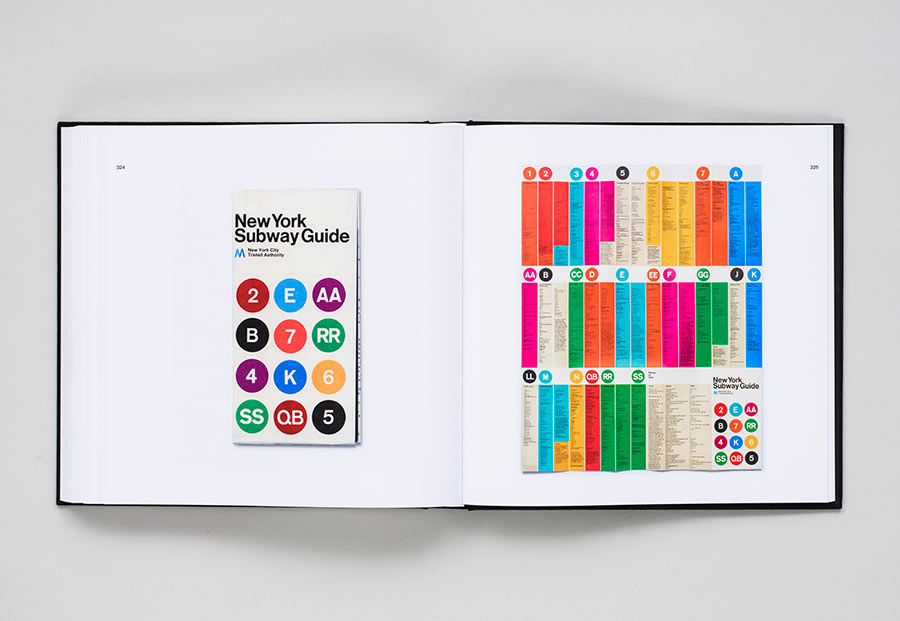

Shepelavy took me on a tour of successful city branding. There is, for example, the MTA signage in New York City, which even has its own branding manual:

That, Shepelavy says, makes the rider say to him or herself: “My city is talking to me.”

There’s Melbourne, Australia, which posits the city as the star of its own movie…and who doesn’t want to be starring in their own movie? Last summer, Edmonton unveiled its narrative as a city of makers, kicked off by Make Something Edmonton, an online forum where 2,000 local residents posted their own stories about what they are building and making.

In her 2008 book, Branding New York: How A City In Crisis Was Sold To The World, Miriam Greenberg shows how New York City turned around its image in the 1970s as dirty, crime-infested and incompetently run. Civic and business leaders joined with Mayor John Lindsay in what might have been the first public-private partnership. Together, they set about cleaning up the city—and documenting it, culminating in Milton Glaser’s groundbreaking I Love New York ad campaign.

“What if we use our challenges to rebrand and tell the story of Philadelphia?” says Brigitte Daniel. “We should brand ourselves as a social impact innovation hub, a place that is better than other cities at inclusion and collaboration, all in service of addressing social problems.”

What’s the common thread between New York’s long-ago comeback, and the Melbourne and Edmonton rebrandings? All were the product of what Shepelavy calls “rigor” and what Katz and Nowak call “horizontal leadership.” They involved diverse stakeholders coming together, asking tough questions of others and about themselves, and coming up with an authentic idea that defines who they are as a city, and where they’re going. In that sense, the process that led to the Amazon pitch can be seen as the first step—but only a first step—of that rigorous process.

The Amazon pitch video is an energetic and cool list of attributes that make you feel like we’re a city on the move. But it only hints at a bigger story, like when badass La Colombe founder and CEO Todd Carmichael says, “This is the city that invented modern Democracy and we didn’t stop there. This is an incubator city. This is a city that’s almost like fertile soil. You put the seeds here and it will grow.”

That’s an idea that has big-picture storytelling legs. Brigitte Daniel, the Executive Vice President of Wilco Electronics who worked on the Amazon pitch and gave a rousing introduction to it at its unveiling last October, is thinking along the same lines as Carmichael.

“I’ve been having a lot of conversations since we learned we’re in the Amazon top 20,” says the VP of one of the oldest black-owned cable systems in the nation, which was recently bought by Comcast. “What if we use our challenges to rebrand and tell the story of Philadelphia? We should brand ourselves as a social impact innovation hub, a place that is better than other cities at inclusion and collaboration, all in service of addressing social problems. Every startup I know wants to be part of driving social purpose.”

Daniel’s idea couldn’t be more timely. Last month, Laurence Fink, founder and CEO of the $6 trillion investment firm BlackRock sent a groundbreaking letter to the CEOs of the world’s largest public companies that essentially told them to do good—or risk losing his investments. “Society is demanding that companies, both public and private, serve a social purpose,” he wrote. “To prosper over time, every company must not only deliver financial performance, but also show how it makes a positive contribution to society.”

![]() Fink’s message goes beyond a call to charity or what’s come to be seen as corporate social responsibility. It’s a call to be part of the horizontal leadership Katz and Nowak talk about. To not only be at the problem-solving table, but to lead the discussion. In effect, both Carmichael and Daniel are asking: How cool would it be for that to be Philly’s new place in the world? To be seen as a groundbreaking problem-solver, just like some 240 years ago, when a bunch of dudes wearing wigs in a basement at 7th and Market wrote up the most audacious plan for self-government known to man.

Fink’s message goes beyond a call to charity or what’s come to be seen as corporate social responsibility. It’s a call to be part of the horizontal leadership Katz and Nowak talk about. To not only be at the problem-solving table, but to lead the discussion. In effect, both Carmichael and Daniel are asking: How cool would it be for that to be Philly’s new place in the world? To be seen as a groundbreaking problem-solver, just like some 240 years ago, when a bunch of dudes wearing wigs in a basement at 7th and Market wrote up the most audacious plan for self-government known to man.

To do that, it would require shedding the curse of incrementalism that has come to define our local public life. And it would demand we tell ourselves that we’re more than the familiar story we’re used to.

Look, I, too, was amused by Jason Kelce’s rant last week during the parade. But, in its resentment, in its snarl, and in its, uh, Mummery, it also conformed to our old story, didn’t it? That’s part of who we are, yes, but it’s not the sum of us.

Predictably, the national press lapped up the Kelce spectacle. But I wish they’d also focused on Doug Pederson announcing that championship parades are now our “new norm.” Kelce singled out the naysayers, but Pederson focused on the doing. Maybe, to extend the metaphor, the Eagles’ coach is also who we are: Innovative and fearless, a gunslinger who led the NFL in 4th down risk-taking with a relentless work ethic. Maybe the new Philadelphia story is, just like the Eagles and their parade, a communitarian dream, where black meets white, young meets old, gay meets straight, and, in the end, old becomes new again.

Photo courtesy R. Kennedy / Visit Philadelphia