“Never forget.”

It’s a sentiment that’s deeply woven into post-World War II Jewish culture, a phrase as familiar to students in suburban Hebrew schools as it is to congregants in city synagogues and retirees on the tennis courts in Boca.

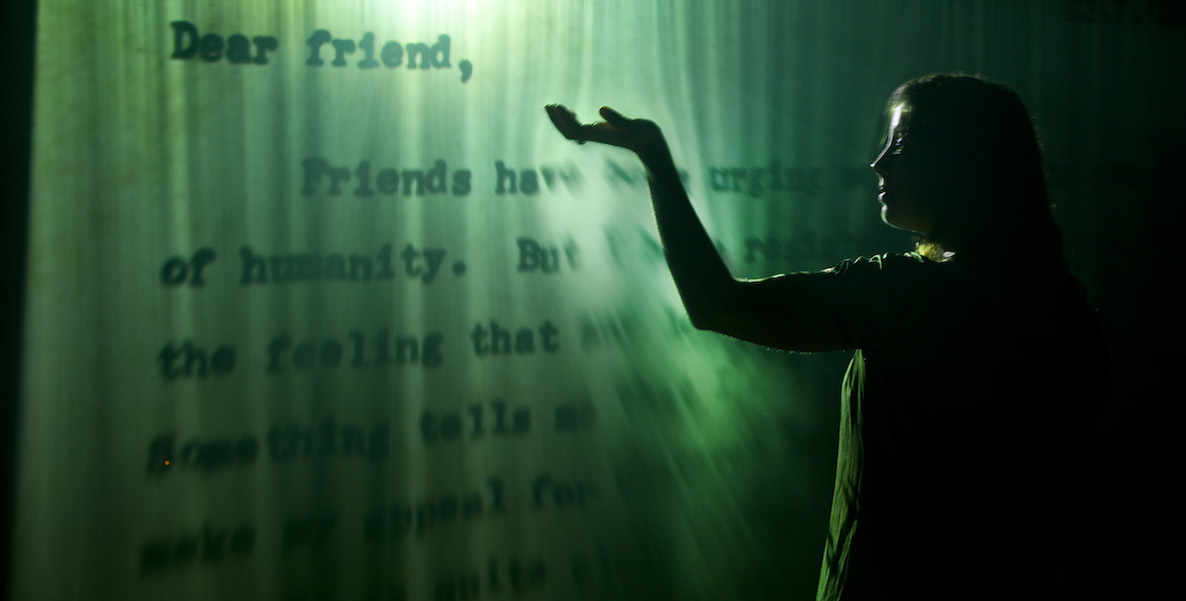

Those two words are a reminder and a call to action, imploring Jewish people to remember the tragedy of the Holocaust and the stories of the six million Jews who died, so that it may never be repeated again.

![]() And yet 75 years after V-E Day, when Germany ultimately surrendered to end the war, we are witnessing an unprecedented spike in acts of anti-Semitism. Last year, according to Anti-Defamation League (ADL), there were 2,100 documented anti-Semitic incidents, the highest number since the organization began its tracking 40 years ago.

And yet 75 years after V-E Day, when Germany ultimately surrendered to end the war, we are witnessing an unprecedented spike in acts of anti-Semitism. Last year, according to Anti-Defamation League (ADL), there were 2,100 documented anti-Semitic incidents, the highest number since the organization began its tracking 40 years ago.

In Philadelphia, we are watching history unfold this very week as the chorus of voices calling for the resignation of the head of our chapter of the NAACP grows louder, in the wake of that leader’s anti-Semitic online posts.

It is why the educational work of Philadelphia Holocaust Remembrance Foundation (PHRF), and the Horwitz-Wasserman Holocaust Memorial Plaza it developed and oversees at the corner of 16th Street and the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, continues to be more imperative than ever.

And it is with this lens that guests joined PHRF and The Citizen last week for a Zoom chat with Dr. Robert Watson and Citizen co-founder Larry Platt, with introductory remarks by PHRF Executive Director Eszter Kutas and David Adelman, who chairs PHRF’s board and sits on The Citizen’s board, as well.

Watson is Distinguished Professor of American History at Lynn University, and the author of more than 40 books. His latest, The Nazi Titanic, has done what Platt says all journalists dream of doing: unearthed something previously unknown to the masses. That something is the tragic fate of the German ocean liner SS Cap Arcona which, in the final days of the Third Reich, was packed with thousands of concentration camp survivors and mistakenly bombed by the British Royal Air Force.

“You found a story that none of us knew existed, in an area where I thought there were no more new stories,” Platt said to kick off the discussion.

Watson went on to explain his accidental discovery of a letter that set his research journey in motion.

“I think every paleontologist dreams of putting a shovel in the ground to start a garden, and pulling up a new dinosaur,” he said, by way of analogy. “As an historian, I think I’ve found a couple of good stories in my career, but nothing like this. I’ve always said that quite simply there’s more we don’t know about history than we do know about history.”

Watson had intended to write a book about the last week of World War II in Europe. “I’m such a nerdy historian,” he said with a laugh. His goal was to develop one story of love, and one story of loss. “That’s what really humanizes such a momentous event,” he explained.

But while he was doing his archival research, he came across a letter from a major in the British army, who wrote that “of all the horrors of World War II, nothing will compare to watching thousands and thousands of Holocaust survivors all die at the end of the war when we were signing a surrender.”

Watson was flabbergasted.

“I got the letter and I went What is this? I’ve never heard of this.” He called The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in D.C., The National WWII Museum in New Orleans; he emailed Yad Vashem in Jerusalem and Imperial War Museum in London. Nobody knew anything of it. He spent days in archives, and ultimately found another letter, this one from a British general who was the one on the beach when everybody aboard this ship, dubbed The Nazi Titanic, died.

Bolstered by his discoveries, Watson switched gears and dove headfirst into further research, putting pressure on himself to bring the book the life as quickly as possible, while the last Holocaust survivors are still alive. The resulting tome explores questions of politics and policy, heart and humanity.

As the event wound down and audience members shared their questions and comments for Watson, at least three revealed that they had relatives who’d survived the Nazi Titanic. Floored, Watson encouraged them to reach out, as it became readily apparent that history is always being unearthed, that there is so much more to learn and to share, and that we must all do our part to keep history alive.

“For the words never forget […] to really have resonance, we have to re-teach every generation,” Watson said. That’s just what he did.

To learn more about PHRF, read our previous coverage here, and visit the Horwitz-Wasserman Memorial Plaza. And be sure to stay tuned for information about The Citizen’s upcoming events, which will resume with gusto in September.

Want more? Check out recaps of our other recent virtual book club events.