“I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived. I did not wish to live what was not life, living is so dear; nor did I wish to practice resignation, unless it was quite necessary. I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow life, to live so sturdily and Spartan-like as to put route all that was not life, to cut a broad swath and shave close, to drive life into a corner, and reduce it to its lowest terms, and, if proved to be mean, why then to get the whole and genuine meanness it, and publish its meanness of it, and the world; or if it were sublime, to know it by experience, and be able to give it a true account of it in my next excursion.” — Walden

Henry David Thoreau did not walk into the woods to lose weight. By all accounts, he was not obese. As a victim of tuberculosis at an early age, he most likely had more trouble keeping weight on than taking it off. He did not write the classic nineteenth-century transcendentalist work, Walden, to help his readers lose weight. He seemed more interested in the length of his nose than the breadth of his waistline.

There is an old joke among Thoreauvians (I kid you not, that is what fans of the nineteenth-century Transcendentalist are called) that Thoreau spent half his life at Walden Pond and the other half in jail. Henry David Thoreau spent, in fact, two years, two months, and two days in the wilderness of Walden Pond outside Concord Massachusetts (July 4, 1845 – September 6, 1847). His experience in the woods is memorialized in Walden.

He spent one day, July 23, 1846, in prison for refusing to pay a poll tax on the grounds that it was funding the Mexican-American War which he opposed. His jail time was cut short due to the payment of his tax obligations by an unknown benefactor. The experience in the Concord township jail was memorialized in his treatise, Civil Disobedience. Walden’s two years in the woods were spent outside Concord, Massachusetts. He lived in a small log cabin that he built on the property of his good friend, mentor, and benefactor, the nineteenth-century Transcendentalist, Ralph Waldo Emerson.

Simplify your life by limiting the amount of junk you consume — in all of its non-eating aspects —and you will trigger your brain and body to not desire junk in your food diet.

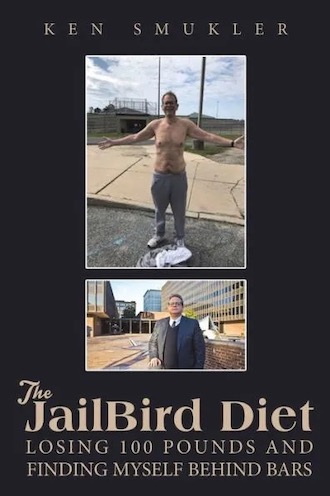

On June 17, 2019, I went into the woods of Fairton Correctional Institute outside Millville, New Jersey — 340 miles south of Walden Pond and 174 years later. I surrendered myself to the woods. I did not pick the time and place; a federal judge did that for me. I had no goal other than to survive. I answered to uniforms every day. I came in as a number — 76315-066 — and left 308 days later as that number.

Though Walden Pond and the satellite camp at Fairton are separated in time and space, the principles guiding Thoreau’s journey into the woods are the very principles that guided my weight loss journey; the principles that provided me the structure and foundation upon which I set out to live my life away from family, friends, and the rest of the free world.

These pages lay out the weight loss plan I structured for myself from the first day I entered my woods to the day I returned to the free world. To successfully carry out this weight loss plan does not require the recording of calories, though you will be recording what you eat every meal of every day through the journey.

As Thoreau recorded what he planted and the costs of every item used to build his house and maintain his diet, you will record your journey.

The Jailbird Diet does not require you to choose certain foods over others, though it does require you to diligently restrict the amount of junk in your lifestyle; it does not tell you the super foods you should eat to maintain a healthy diet while losing weight but it does tell you the super “foods” you should incorporate into your life to sustain short-term significant weight loss. The Jailbird Diet does not focus on the pyramid of food groups but on the myriad of day-to-day choices beyond food that will predict whether or not you have what it takes to sustain a short-term weight loss program.

Thoreau left society and placed his entire mind and body into the wilderness; he wanted for nothing that he had left behind in the town of Concord. In fact, he disdained much of what he found there: the commerce, the trappings, the gossip, the petty, the morally reprehensible, what he called “most of the luxuries, and many of the so-called comforts of life” — what I call the junk — all of it to be left behind to live in an exalted state within the woods.

“I learned this, at least, by my experiment: that if one advances confidently in the direction of his dreams, and endeavors to live the life which he has imagined, he will meet with a success unexpected in common hours. He will put some things behind, will pass an invisible boundary … In proportion as he simplifies his life, the laws of the universe will appear less complex and solitude will not be solitude…If you have built castles in the air, your work need not be lost, that is where they should be. Now put the foundations under them.” — Walden

If there is any secret to my diet success, it is this: Simplify your life by limiting the amount of junk you consume — in all of its non-eating aspects — and you will trigger your brain and body to not desire junk in your food diet and, in so doing, lose weight. Replace the junk in your day-to-day life choices with healthy day-to-day experiences that challenge your mind and body and hunger will dissipate even as your body confronts a highly restrictive diet.

Place yourself within a solitude that rejects junk, in all of its non-food forms, replace that junk with super “foods” that engage your mind, body and soul, and you will succeed.

The Jailbird Diet is driven by lifestyle choices rather than food choices. Thoreau achieved this lifestyle by walking into the woods and staying there for two years. I did it through a forced incarceration over ten months. But you need not physically remove yourself from society to clear out your junk files.

Thoreau recognized this.

“A man thinking or working is always alone, let him be where he will. Solitude is not measured by the miles of space that intervene between a man and his fellows. The really diligent student in one of the crowded hives of Cambridge College is as solitary as a dervish in the desert.” — Walden

Solitude can be achieved anywhere. Solitude is a state of mind.

His approach to the junk of the nineteenth century informed my approach to the junk of the twenty-first century each and every day I was incarcerated. It was this approach that guided my mind toward a rigorous discipline of junk removal that allowed me to sustain my weight loss program.

I began to treat everything that I consumed, beyond what one traditionally associates with weight gain — namely food — as part of my diet. Junk food was not simply what I put into my mouth, it was what I put into my mind: junk food was not simply potato chips and candy, stromboli and pizza, but junk news, junk books and magazines, junk television, junk Internet, junk relationships, junk business, junk science, junk communication, junk photos, and junk videos.

“What is the pill which will keep us well, serene, contented? For my panacea, instead of one of those quack vials of a mixture dipped from Acheron and the Dead Sea…let me have a draught of undiluted morning air. Morning air! If men will not drink of this at the fountainhead of the day, why, then, we must even bottle up some and sell it in the shops, for the benefit of those who have lost their subscription ticket to morning time in this world.” — Walden

When Thoureau speaks of breaths of fresh air as an elixir, he is not simply speaking to the air he breathes but to everything else he no longer breathes. He called the junk “not only not indispensable but positive hindrances to the elevation of mankind. With respect to luxuries and comforts, the wisest have ever lived a more simple and meager life than the poor.”

We all accept as Gospel that removing junk food from one’s diet is a necessary prerequisite to short-term weight loss. It is time we accept that removing junk media, junk internet, junk television, and junk relationships is equally necessary to achieving weight loss success. I came to realize that these non-food junk “foods” were hunger triggers for me; by removing them, I took hunger off the table. My body and mind no longer recognized and reacted to hunger signals and began to accept the long-term reduction in my food and caloric intake. That this happens as a fact I know because for ten months I lived it. You do not need to go to a fat camp or spa to put yourself in a position to lose weight. You do not need pre-packaged foods or a number system. You do not need pills or medication. And you do not need to starve yourself. You do need, however, to prepare your mind and body for such a journey.

My new eating habits were merely the symptoms brought on by a vigorous adherence to a daily mental and physical regime that removed food from the equation.

It was not the food choices that I made in prison that drove my weight down; it was how I decided I would live my life in prison that allowed me to make the food choices that ultimately led to significant sustained weight loss.

It was everything that happened outside of the time I was sitting at a table in the chow hall that caused my drop in weight; my new eating habits were merely the symptoms brought on by a vigorous adherence to a daily mental and physical regime that removed food from the equation. As I came to understand in the early days of my incarceration, if the regimen removes hunger from the equation, food becomes fuel to be burned and nothing more.

Can Thoreau’s approach to living be adapted to the pursuit of significant weight loss? Can an overarching life-changing plan to simplify your existence on this earth be the very plan that can successfully launch a short-term large scale weight loss program? One that could melt 25–30 percent of your body weight away? One that could result in your losing 100 pounds in less than a year? Can limited caloric intake be sustained over the short term not because you willed it or pilled it but because you didn’t focus on the food part of dieting but focused on everything else in your life except for the food? Can the key to short-term weight loss have nothing to do with your food choices and everything to do with all the choices you make when you are not eating?

Can hunger be satiated, not by drugs or sheer willpower, but by fundamentally simplifying your lifestyle? If you remove all that junks up your life, can you then more easily remove the desire for food that junks up your diet?

Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes. And yes.

For me, it required a sustained physical, mental, and emotional solitude that is very difficult to achieve in the free world.

Shock and awful

I could not but smile to see how industriously they locked the door on my meditations, which followed them out again without let or hindrance, and they were really all that was dangerous. As they could not reach me, they resolved to punish my body; just as boys, if they cannot come at some person against whom they have a spite, will abuse his dog…Thus the State never intentionally confronts a man’s sense, but only his body, his senses. — Civil Disobedience

Thoreau built a small cabin in the woods, spent his days outside raising crops and walking in the woods, and spent his nights reading and writing. Incarceration in a federal prison camp allows for a very similar existence if you set yourself to the task of living as simply as possible.

A bunk to sleep in, a place to walk in the woods, nights spent reading and writing — these defined my experience in federal custody: an environment totally unlike that in which I was raised, worked, and lived for the 58 years prior to June 17, 2019; an environment only those in federal custody can understand; an environment I call, “Shock and Awful.”

As I write this, I am sitting in a 7-foot-by 9-inch cell looking out a barred window across a prison yard crisscrossed by razor wire. You want to find a really good place to get your head around a long-term weight loss plan? This is the place.

But this is not where I started. This is where my journey will end. I move my chair to face the window. In the far-left corner of my sightline over and above the razor wires I can just make out the building where my journey began ten months ago – R and D, Receipt and Discharge.

It is time we accept that removing junk media, junk internet, junk television, and junk relationships is equally necessary to achieving weight loss success.

R and D is the perfect orientation for a prisoner entering a federal correctional institution as a self-surrender (e.g. not dropping down from a higher security facility as the majority of inmates did at my camp); its very name triggers your self-identification as something less than human.

The first interaction with a prison guard is the take-off-all-your-clothes strip search — pull your package up for the full frontal, bend over for the anal cavity peak on the back side. Thus begins the transformation from human being with a soul to institutional package with a SKU number and barcode: A number and code that is never to leave you; one that is entered when you talk on the phone, send email, receive snail mail, when you are called to the office and when you go to see visitors.

Entering prison is, in many ways, like entering a public high school in the 1960s and 70s: cinderblock walls, linoleum floors, industrial lighting, industrial cleaning, all metal and plastic everywhere you go, everything you touch, all that you smell, see, hear, taste … all concrete, metal, plastic, and industrial cleaning products.

This artificial industrialized sensation overload plays with your mind. Noises that may have caused you to jump back on the outside become as inconsequential as the purr of a kitten. You never walk around barefoot, indoor, outdoor, certainly not in the bathroom or shower.

There is no real measure of ambient light streaming into any indoor area — not where you eat or where you sleep. The indoor light hits you from 35 feet above like the light of an oncoming train.

The forced air cools both housing unit and chow hall to temperatures well below what your home thermostat would call for even on the hottest of summer nights. It was not uncommon to see men in full sweats, scarf and knit hat watching television in the chow hall in the middle of July. I was told that the frosty clime was to keep flies and insects to a minimum just as the din of the industrial fan running 24/7 in the bathroom was to keep sounds and smells to a minimum and, as everything in BOP [Bureau of Prisons]-land happens for a reason no matter how illogical or inane, I guess these measures worked.

It’s not simply that your world is thrown upside down when you enter a federal prison. It’s that your world in every sensation becomes louder, brighter, colder, rougher, smellier. All of your senses bombarded, putting your whole body on edge. Guys sleeping with their CPAP machines disconnected creating a cascade of snoregasms; 60 bunk beds lined up in a warehouse in which the men slept, as Joseph Conrad described in Heart of Darkness, “with all the taps turned on.”

In the chow hall, hard plastic cups, sporks, discolored plastic dining trays like oversized Swanson Hungry Man TV dinners. I came to crave silverware, china, glassware almost as much as I craved a lobster roll or grilled fish. In the bathroom, if the industrial fan and hand blowers aren’t assaulting your auditory senses, the scalding water that hits your body from the showers will — it leaves you breathless. (Aside: This is a story that will tell you all you need to know about the Catch-22 that is the BOP — or as one administrator called it, the BOP — Broken On Purpose. When I got to camp, the shower stalls were equipped with a metal button connected to the waterline leading to the shower head — this button you would push to maintain water pressure like the morphine drip button in a post-op hospital bed. There was no regulator for hot or cold. This led to moments when the water temperature would spike to scalding without warning. I was told that the BOP implemented this system in order to economize on water usage and not overtax the hot water heater. The campers, as they routinely do, figured out a workaround for the scalding: Turn all the sinks’ hot water on full blast and leave all ten running while you take your shower.)

Your sense of space also takes a hit. I am sleeping two feet above another human being, two feet next to two others with a corridor of human traffic flowing by the other side of my bed at all hours, day and night. The sound of walkie-talkies, boots, jangling keys, and the idle conversation of guards hits at regular intervals of the night at 12:30, 3:30 and 5 am, as the cops make their rounds through the housing unit. If you choose to hang out at your bunk, you will be doing so with someone talking, eating, sleeping, snoring or farting within arm’s length at all times.

If the constant assault on all senses did not place my body onto a wartime footing, the precariousness of my health and well-being did. I came to camp with nerve damage radiating down my left leg leaving me with a dropped left foot. I came armed with two doctors’ notes warning of the hazards of my attempting to mount the upper berth of a bunk bed (I had been alerted to the existence of bunk beds at the camp by a former inmate). Upon presentation of these notes to the Camp Counselor at R and D, I was immediately assigned to bunk 24 U — U standing for Upper. So much for doctors’ notes.

![]() MORE ON GETTING PAST PRISON FROM THE CITIZEN

MORE ON GETTING PAST PRISON FROM THE CITIZEN