Sudan Green was brought up by a village.

“Community has literally raised me,” he says.

Attend Spirits up!Do Something

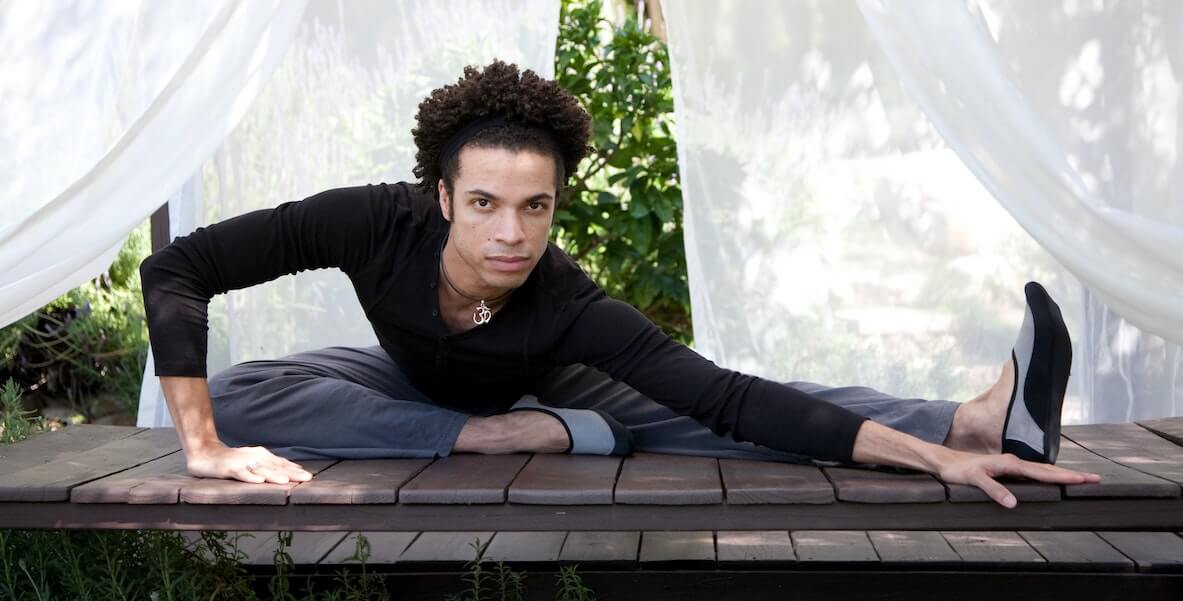

But there remains one community in which Green, a 25-year-old musician and activist, rarely, if ever, sees people like him represented: the yoga scene.

“In the five years I’ve been practicing yoga, I could probably count fewer than 20 black people who’ve been in class with me,” he says.

Even in a diverse city like New York, where Green lived from 2013 to 2016 and began practicing at Yoga to the People, a free studio in the East Village, there were so few faces like his.

That, Green says, is too bad: He thinks group yoga has countless benefits. Yes, studies have shown its potential to relieve stress and anxiety and improve sleep, endurance, and flexibility. But its power right now lies in its ability to help heal. And it can be transformative, Green says, to practice with people who can deeply empathize with your experience. “If representation is important in pop culture and toys, it is extremely important in spiritual healing.”

“A lot of my friends and my brothers and the people in my community don’t practice yoga and they could benefit from it so much. But how can you expect someone to try to heal if the tools aren’t there for them or geared for them?” he says. “Many people are afraid and don’t feel comfortable in yoga studios when they look around and there’s no one who even remotely looks like them.”

There are so many experiences that are at once unique to and universal among black Americans that are simply not relatable to predominantly white yoga devotees. By way of example, Green shares that his beloved friend was murdered last year; he feels bereft, and knows he’s not alone.

“How can a black woman or black man feel comfortable going in and releasing so much of themselves when you don’t want the I’m sorrys, you want the I feel yous?” he wonders. You can go from wanting to heal, he says, to being triggered instead.

Green has longed to complete yoga teacher training and open a studio for the black community. And this week, recognizing the trauma and tumult of the recent protests in particular, he’s kicking off an initiative that reflects his commitment to healing black people through yoga: Spirits Up! will provide six days of free outdoor yoga, meditation, and guest speakers for black people and protesters from 1pm to 4pm, at locations around Philadelphia like the Municipal Building (where the Rizzo statue was removed), Washington Square, Rittenhouse Square, Logan Circle, Vernon Park, and Malcolm X Park, the site of the final gathering on Juneteenth.

The choice of locations was influenced by Smith’s recommendations and done with intention: Some of these squares used to be burial grounds for African bodies, slave bodies.

“There’s an untold number of dead bodies underneath Washington Square and people don’t know that. So to meditate and do yoga there will be a really healing moment,” Green says. “Logan Circle used to be an execution circle, so who knows what kind of things went on there.”

And Rittenhouse Square?

“Everybody always says that we’re stronger together, and that’s something that this time has really shown me, how powerful we are. When a national problem arises, we make changes,” he says.

It’s important to Green to bring the movement there in large part because of an experience he had while riding his bike home to Brewerytown on the first day of the protests. He’d just witnessed cars burning and people being maced while fighting for their lives, but when passing the square, white people were gathering, mask-free, nonchalantly having picnics without any repercussions for ignoring social-distancing guidelines. He says he felt disgusted.

In the span of less than two weeks since that evening, he was able to put the program together, with the support of Smith and Denenberg’s Little Giant Creative and Councilperson Cherelle Parker. He also secured 250 free yoga mats for participants (everyone will be required to space their mats six feet apart, and wear a mask at all times; Green is emphatic about following safety protocol).

The roster of teachers was hand-picked by Jean-Jacques Gabriel, the owner of West Philly’s Studio 34 Yoga, one of the few black-owned yoga spaces in the city and a big inspiration to Green. Speakers, who will kick off each session, will include Poet Laureate Trapeta B. Mason, Wallo 267, some of Green’s lifelong mentors, like Smith and Rucker, his mom, and could include other black leaders like Marc Lamont Hill.

Anyone is welcome to attend, but he’d especially like to see white members of the community come out to volunteer with tasks like setup and cleanup, and making sure people’s mats are appropriately spaced and that everyone has a mask, so that black members of the community can truly focus on healing.

Green hopes that calling attention to the need for yoga spaces for black people this week drives support of his bigger-picture vision: To raise enough money—$250,000—to get a brick-and-mortar space, ideally in Germantown, as a site to train 10 to 15 local black yoga instructors, and then use the space as a center for yoga and possibly even rock-climbing, another activity Green enjoys but through which he’s encountered few other black people. “We get in trouble for climbing walls, but I’d love to invite kids to come in and do it,” he says.

He’d also welcome the chance to partner with the School District of Philadelphia, to create an alternative to disciplinary actions like detention and suspensions. “I want to be able to offer a class once or twice a week where, instead of detention, kids would come to a yoga class in Germantown,” he says.

“I know a lot of people don’t have community, and how can they, when there are no community centers, or if there are, they’re not funded property. They don’t look as nice as the community center in Ardmore,” he says.

And while he feels blessed, privileged, to have always grown up around community, Green says it’s been the protests this week that have driven home more powerfully than anything the importance of communal support.

“Everybody always says that we’re stronger together, and that’s something that this time has really shown me, how powerful we are. When a national problem arises, we make changes,” he says.

You can be part of those changes. Donate to the GoFundMe. Tell the people in your yoga circles to rally their community to support teacher-training scholarships. And encourage your black family and friends to get the self-care they deserve. Because taking care of yourself, getting help from your community, doesn’t make you weaker—it makes all of us stronger, together.

Sunday–Friday, June 14-19, 1pm-4pm, free, various locations.

Header photo by Patrick Malleret on Unsplash