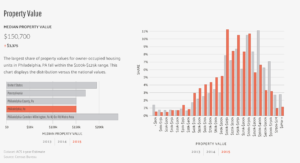

New construction of homes and office buildings is an important part of Philadelphia’s continued economic growth. And Philly’s generally done a lot better than many other cities at building enough homes to keep up with the demand for housing.

That’s been less true recently, but unlike places like San Francisco and New York City, Philly really hasn’t allowed a large gap to open up between the demand for housing and the supply of housing, and the volume of construction has kept home prices generally affordable for middle-class people, if not always in the most high-amenity neighborhoods in the very center of town

Unfortunately, some politicians and activists look at the neighborhood changes associated with this brisk pace of home construction, and mistakenly conclude that lots of new construction is a threat to Philly’s affordability edge. Really, it’s the main force keeping home prices from getting out of control.

The paradox of the whole gentrification and affordability debate is that, to stave off unaffordability, neighborhoods need to change faster, not more slowly.

Once land values start to appreciate, slack housing markets with lots of new construction are better for lower-income residents than tight housing markets with less new construction. That’s because wealthier newcomers will always be able to outbid existing residents for the existing houses, but if developers are continually building newer houses, there’s less direct competition over a fixed pie of homes, and consequently, less actual displacement.

Matthew Yglesias at Vox says people need to look at the problem through this lens and decide what’s more important to them: keeping neighborhoods affordable or keeping them aesthetically the same.

Where land is even scarcer, American builders have the capacity to erect apartment buildings—some of them two dozen stories high or more—whose floors are connected by elevators. The big problem is that in the most expensive metropolitan areas it is illegal to deploy these technologies on large swaths of land. Zoning codes and historic preservation rules generally prevent even the priciest neighborhoods from becoming denser.

The checks wouldn’t need to be very large. They would have psychological value in addition to material value, communicating a clear political message that everyone should share in the benefits of growth.

Relaxing these zoning rules would transform gentrification of neighborhoods in generally affluent cities into a win-win that benefits the poor. But it would mean accelerating the pace at which gentrification reshapes the built environment of those neighborhoods. Those worried about gentrification, in other words, likely need to choose what it is they are primarily worried about—the aesthetic or economic dimensions of the issue—and recognize that addressing one will likely exacerbate the other.

Getting this frame of the issue to stick politically is easier said than done, and part of the problem is that the proposed policy responses that affordable housing advocates keep putting out frame the issue in a defensive way.

Ideas like the flip tax or impact fee proposed by the Coalition for Affordable Communities to fund the Housing Trust Fund, however well-intentioned, tell a problematic political story in which new housing is having a negative impact on neighborhoods, and so we need to tax new construction in order to offset that negative impact.

While housing construction may have some very local costs for quality of life (construction noise, parking), it’s good for the city and for neighborhood businesses to have a growing population and lots of new home-building activity. It means the neighborhood can support more amenities, including businesses, public goods, and community capacity.

But neighborhood-level politics at the RCO level tends to underrate the citywide and neighborhood-wide benefits of more housing, and focus an excessive amount of attention on mitigating these very localized costs. To change the politics, we have to change this dynamic and make those local parties whole in some way.

The best way to do it is by sending them a check in the mail whenever a nearby building goes up—call it a gentrification dividend.

The 10-year tax abatement for property improvements has been an important tool for papering over Philly’s high construction costs, but has had an unfortunate side effect of severing the political connection between building more buildings and getting more property tax revenue. To remind people of this fact, and also send a message that everyone should benefit as the neighborhood grows, near neighbors of a new construction project should get a check in the mail from the City with a cut of the development property’s tax increment for the year.

Read more about housing in PhiladelphiaRead More

This idea was first proposed by David Schleicher of George Mason University with the concept of TILTs—Tax Increment Local Transfers—where neighbors of a development project could share in some of the proceeds from the new taxes that the new building generates. Since Philly’s 10-year abatement means the revenue doesn’t come in for 10 years, the TILTs could be funded out of the tax revenue that’s starting to come in from expiring abatements.

Last week, Emily Hamilton, Policy Research Manager for the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, suggested an interesting adaptation of this idea, that would use part of the tax increment from new development to fund causes that anti-displacement activists care about. Locally, the target would likely be the Housing Trust Fund.

In addition to building support for new housing and reducing gentrification pressure on the supply side, TILTs could also provide a revenue source for housing vouchers. A TILT for affordable housing could be structured in several different ways. The funds could be used to provide housing vouchers to city residents who meet established income requirements. Or the funds could be dedicated specifically to residents who lose rent-controlled apartments to new construction.

Unfortunately, some politicians and activists look at the neighborhood changes associated with this brisk pace of home construction, and mistakenly conclude that lots of new construction is a threat to Philly’s affordability edge. Really, it’s the main force keeping home prices from getting out of control.

TILTs have the potential to be a significant revenue source. While tax increment financing (TIF) is a distinct concept from TILTs (and TIFs raise fiscal and equity concerns), TIFs provide some indication for the revenue-raising potential of TILTs. In Chicago, TIFs generate $500 million annually. The more constrained a city’s housing supply is, the more potential it has for substantial tax increments as a revenue source. In “City Unplanning,” Schleicher suggests that 25 percent of the tax increment of new development could be share with property owners who live near new development. Another 25 percent could be dedicated to housing vouchers. If TILTs lead to approval for projects that would have otherwise been blocked by homevoters and/or anti-displacement activists, they would still provide an increase in cities’ general property tax revenues.

See how our city has changed over the decadesVideo

A better approach would be to encourage more market-rate growth, and use some of the increased property tax increment—pulled from 10 years in the future—to fund housing vouchers or home repairs or checks in the mail to near neighbors.

Jon Geeting is the director of engagement at Philadelphia 3.0, a political action committee that supports efforts to reform and modernize City Hall. This is part of a series of articles that will run in both The Citizen and 3.0’s blog .

Header Photo: Emma Lee