News of free food spreads like wildfire on any college campus—especially with the help of technology.

At the end of Temple’s 2018 fall semester, Kim Celano and Phillip Smith were together at the Division of Student Affairs staff celebration. It was a catered party, and—as often is the case— there were lots of leftovers.

![]() “It was good food,” remembers Celano. “There were about 80 sandwiches on one tray alone; meat and cheese and fruit.”

“It was good food,” remembers Celano. “There were about 80 sandwiches on one tray alone; meat and cheese and fruit.”

From the many other campus events they’d attended and hosted, they knew it was destined for the trash.

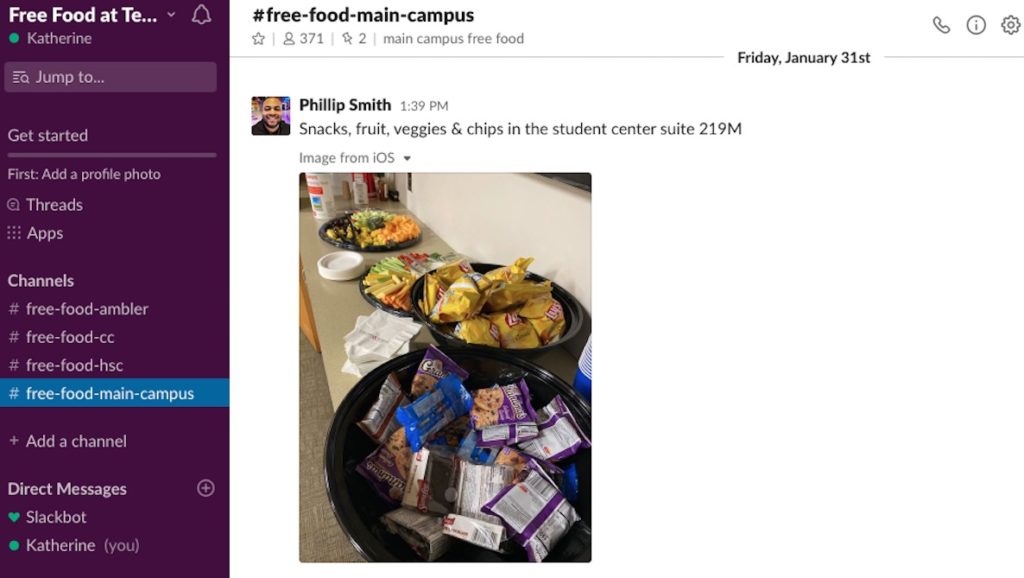

Smith pulled out his phone, started a group in the messaging app GroupMe, and posted photos of the food. He included the location and a caption: all this food is free; tell your friends. “In 10 minutes we had students lining up out the door,” Smith says.

Within a couple days, the chat group was almost full (the app caps at 500) and students and faculty followed Smith’s simple format to spread the word about free food opportunities across campus including leftovers, open events with free food, and random giveaways.

![]() Celano and Smith had implemented a simple solution to two issues they dealt with regularly.

Celano and Smith had implemented a simple solution to two issues they dealt with regularly.

Celano, the associate director of student operations in the student center, works in facilities behind the scenes, prepping rooms for the jam-packed schedule of meetings and presentations.

After events, they throw out a lot of food, Celano says. “We have an hour to turn over the room and we didn’t have a mechanism to put this food anywhere that people would find it.”

Similar post-event waste happens all over campus.

Now, instead of dumping trays of leftovers straight into the trash, her team can snap a couple photos, note the location and time the food is available until, and put out containers—students come to fill up a plate or take food home.

They haven’t attempted to track the numbers, but Celano estimates they’ve kept hundreds of pounds of food from being thrown away. Which, of course, is not just detrimental in terms of the wasted resources that went into growing, transporting and preparing the food; it’s also environmentally costly in the landfill, releasing methane as it breaks down.

They haven’t attempted to track the numbers, but Celano estimates they’ve kept hundreds of pounds of food from being thrown away. Which, of course, is not just detrimental in terms of the wasted resources that went into growing, transporting and preparing the food; it’s also environmentally costly in the landfill, releasing methane as it breaks down.

For Smith, director of student activities, it was campus hunger that sparked the idea for the group. “Food insecurity was a huge platform for last year’s student administration,” he said.

After the Hope Center for College, Community and Justice released their report Alleviating Poverty and Promoting College Attainment in Philadelphia in the fall of 2018, campus was hit with a staggering statistic: 35 percent of Temple’s undergraduate students are food insecure.

It’s in line with national averages for public institutions—there’s a growing number of hungry college students across the country.

Food can be prohibitively expensive on campuses; at Temple, the cost of an average meal is $7.50 (it’s $5.20 if you purchase a 25-meal-per-week plan and $9 if you purchase a 10-meal-per-week plan). And that’s not necessarily because dining services providers are gouging students—it’s far more complicated than that, explains the Hope Center’s founding director, Sara Goldrick-Rab.

“Temple has faced major state budget cuts,” Goldrick-Rab says. “They have revenue needs, especially to keep up with the things students demand. It is very common for public universities who are faced with budgetary pressures to turn to food and housing as a way to make money.” Plus, it’s hard to offer the incredible choice students demand at an affordable price point.

All of which puts campus meals at a premium that many students can’t afford.

Students from low-income homes who might have received free lunch in high school don’t receive those same benefits when they reach college. And though some qualify for SNAP, many don’t know they qualify or how to sign up. And those that do can’t use their benefits at Temple’s dining halls.

Without financial support from family members or federal programs, thousands of Temple students go without food.

Smith can identify with these students. “My mother had a brain aneurysm when I was 14, so I kind of raised myself,” he says. “I was a college athlete and was not able to work [because of NCAA rules]. If I missed the resident’s hall because of practice, then there was no food. I couldn’t call mom or dad to say hey, can you send me $50, 100? There were a lot of times that I went hungry at nighttime.”

In its first year, Celano administered an anonymous survey to find out how students were using the group. Of the 40 who responded, 33 percent said they were using it primarily to post about free food; 46 percent to find out about free food as a perk; and 21 percent that identify as food insecure.

As one student said in response to the question, How has the Free Food at Temple GroupMe impacted you?:

Before the existence of the GroupMe, there were days when I would go without eating any food. I normalized the practice of being hungry because I thought it was better to be financially stable than to be full but unsure of how I was going to make rent… There have been more times than I can count where I was able to find a meal in a time when I was uncertain where one would come from, all because of the chat. I’ve been able to focus on my studies without having to root through trash or ask friends for support to find food.

“We knew [hunger] was out there, but it really humanized it to hear these personal accounts of the impact of this simple thing that we thought of,” says Celano.

This type of food recovery solution is implemented in different forms on many campuses throughout the country. There’s the national Food Recovery Network, which has 230 chapters across the U.S.; the Share Meals app started in 2013 at NYU; Sharing Excess, which was founded just across the river at Drexel, and many more.

And there are other anti-hunger initiatives at Temple, too. The University’s CARE team works to connect students with food resources, including information about applying for SNAP benefits.

At Cherry Pantry, which opened in the winter of 2018, students can get groceries and hygiene products once a week—and they don’t have to fill out paperwork or prove their “eligibility.”

Senior AaronRey Ebreo launched Swipes for Philadelphia; a local chapter of the national initiative Swipe Out Hunger that works to donate students’ unused meal swipes to students in need.

This can be a tricky arrangement to work out, as those unused meals are already factored into the food service profit margin, but Ebreo, who was appointed Temple student government’s director of basic needs last year, helped push Aramark Dining Services to donate 1,000 meals as a pilot.

He hopes that after seeing the need (after an overwhelming response to the program, the CARE team implemented a need-based application process and allocates five meals per student) they’ll run a direct donation program similar to ones on other campuses.

![]() Celano and Smith’s project is a small, grassroots effort, but one particularly passionate student helped it grow since its launch is 2018.

Celano and Smith’s project is a small, grassroots effort, but one particularly passionate student helped it grow since its launch is 2018.

Alexis Culp is a masters student at Temple’s College of Education and the volunteer coordinator of Cherry Pantry. She heard about the free food group from a friend when there was still room to join, but she wasn’t happy about the 500-member cap. “It doesn’t make sense to have a free food group that has a student limit,” she says.

So she helped Celano and Smith find a different platform to use; they landed on Slack, which has no cap. It has a few other benefits, too: Slack allows side conversations about a specific post without crowding the main channel, and students don’t have to login with any identifying information.

“It helped remove that barrier for students who do identify as food insecure and feel the stigma of it,” Celano says.

Since they switched over to Slack last fall, they’re building up their audience again; after weeding out last years’ graduates, they have more than 360 members.

They’re continuing to spread the word to student organization leaders, department heads, and faculty across campus, and Culp created channels for the Health Sciences Center, Ambler and Center City campuses, too.

“[Hunger on campus] is a lot more prevalent than you think,” says Culp, who sees 150 to 200 students come through Cherry Pantry each week. “I never knew there were other students who grew up on food stamps, like me; who went to pantries, like me; that food insecurity followed them to college, like me.”

Culp received financial aid (“Which just comes in the form of loans,” she points out) to help cover the cost of tuition when she started college at Temple in 2016. But she was on her own for other expenses like books and supplies, housing, and her meal plan—all of which can add up to more than half the total cost of attending college.

At the start of her freshman year, she purchased a 10-meal-per-week plan, the minimum requirement for students living on campus. The plan costs $1,453—about $9 per meal. And you can only swipe into the dining hall to eat 10 times per week. By the weekend, Culp would only have two meals left, she says.

“On Saturdays and Sundays, I would swipe into the dining hall at 9am for breakfast and I would stay the whole day,” she says. There were other students in the same situation—they’d bring their computers to do homework and a blanket and stay through dinnertime. “I was food insecure, according to my own definition. You don’t know when your next meal is going to come to you, and you have very limited access to nutritious meals.”

As a freshman, Culp was among the roughly 10,000 students who make up that 35 percent of food insecure students on Temple’s campus whose stories and experiences are varied.

Some live on campus with a limited meal plan, like Culp; others live off campus and cook for themselves; and some don’t have reliable housing at all—all struggle to afford consistent, nutritious meals.

And, of course, when that basic need is not met, it’s hard to focus on classes, which means students aren’t as likely to graduate. According to the Hope Center’s report, food and housing instability are key drivers of college dropout rates.

![]() It’s the same story at public universities across the country, but as the poorest big city, it hits Philadelphia especially hard.

It’s the same story at public universities across the country, but as the poorest big city, it hits Philadelphia especially hard.

“Families across the city suffer if the students they have paid tax dollars to educate K-12 get out, go to college and then drop out,” Goldrick-Rab says. “We’re not going to attract employers, we’re not going to increase the number of good paying jobs—we’re going to have tons and tons of people who need our government services over and over throughout their lives, we’re also going to have a real health problem in the city.”

Goldrick-Rab advocates for larger, systemic changes: creating a better dining service business model that decreases the cost of food on campus; implementing more innovative ways to deploy emergency assistance; and adopting policies like the Hunger Free Campus Act introduced by Rep. Malcolm Kenyatta last month.

Grassroots efforts like the Slack group—led by passionate students and faculty—are a meantime solution that show there’s something everyone can do.

Want more? Check out these related pieces: