Editor’s Note: This story first ran last Columbus Day—it seems even more relevant today.

To many people outside the small post-industrial city of Sandusky, Ohio, its reputation is—like our own—a mixed bag. Nestled along Lake Erie, it was recently named the best small coastal town in America by USA Today, and is in the midst of a downtown building boom. But over the last several decades, the diverse city of 25,000 has lost manufacturing jobs and suffered from uneven urban sprawl, and to people in the surrounding suburban and rural areas, the city’s story often begins and ends with struggling schools and crime.

Prefer the audio version of this story? Listen to this article in CitizenCast below:

Audio Player

Vote on November 3Do Something

So a few years ago, when Sandusky community members started planning for the city’s bicentennial celebration in 2018, they looked for ways to take back the narrative about what they consider a strength: the diversity of their population, of which 30 percent are people of color.

“We’ve always allowed it to paint us in a negative light,” Wobser says. “But a lot of people, especially the younger generation, they value diversity. They want to live in neighborhoods that are integrated, send their children to schools that are integrated.”

Almost immediately, this launched Sandusky into the middle of a national discussion about what we here in the city-that-goes-along-as-usual celebrate as Columbus Day. In what Sandusky officials thought would be a “quick win,” they proposed as part of municipal union negotiations in late 2015 that the city drop Columbus Day as a holiday. The union balked at losing a paid day off.

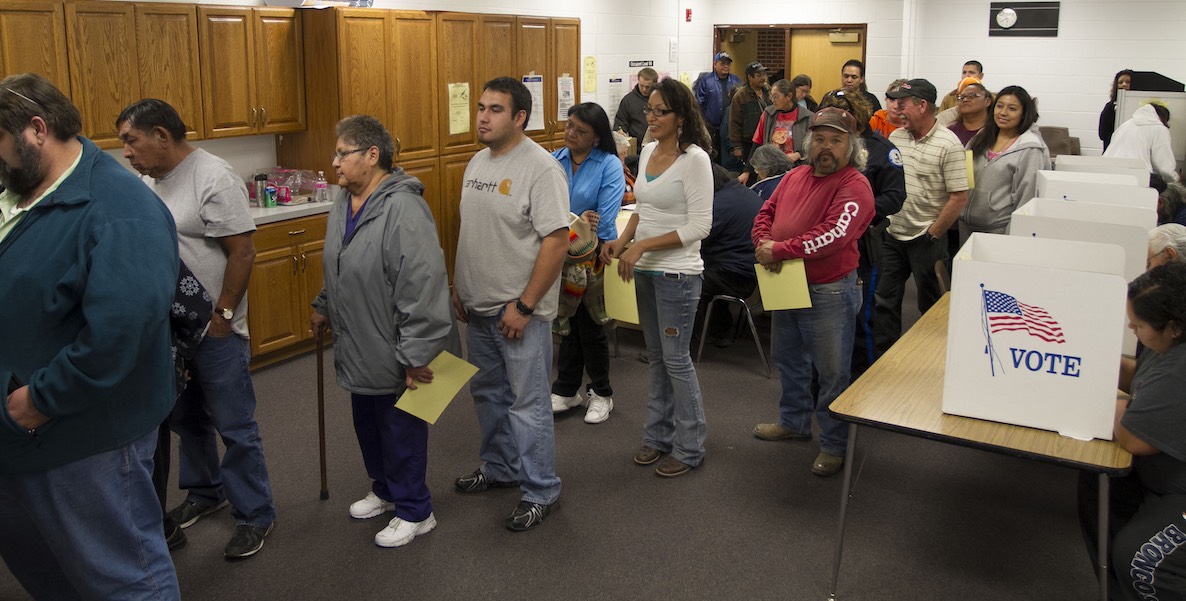

Election Day is already a holiday in many parts of the world, including South Africa, Germany, the Philippines, India (the world’s largest democracy) and our own Puerto Rico, which has no say in electing the president, but still sees 74 percent turnout.

So three years (and one contentious presidential election) later, during the next round of negotiations, they came up with a better plan: swapping one paid day off—Columbus Day—with another—Election Day. That means, for the first time since Columbus Day became a thing, Sandusky city workers are on the job today—but will have all day to line up at the polls on November 5 to cast a ballot in their local election.

Election Day is already a holiday in many parts of the world, including South Africa, Germany, the Philippines, India (the world’s largest democracy) and our own Puerto Rico, which has no say in electing the president, but still sees 74 percent turnout.

Half of the world’s democracies hold elections on Sunday, and 27 of the 36 countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development hold them on a weekend. Meanwhile, we rank 26th in voter turnout, according to Pew.

Advocate for Election DayHave your say

Really, it’s enough to make one wonder why we vote for these people at all. But truth be told: It is the point of our representative government, and voting is the only way to make sure these people are the ones we want. Which is why it should be easier—not just with a paid day off, which some have rightly noted will not solve everything, but also with any number of ways we’ve noted here before: open primaries, ranked choice voting, even-year local elections and lowering the voting age.

As Wobser acknowledges, nixing Columbus Day in favor of Election Day is mostly symbolic in Sandusky: There are only 250 city workers, of whom around 70 police officers, firefighters and the like will still have to work. But the news about their swap hit the same week as the McConnell/Gillibrand dust-up, making national headlines, and it has sparked a conversation both locally and statewide about how other employers could better accommodate workers on Election Day—including some who are considering giving them a paid day, or paid time, off to cast their vote.

“With the backdrop of everything going on with voting rights, voting access, the 2016 election, we knew we had to do something,” Wobser says. “We are proud that we’ve sparked conversation about what local entities can do to increase turnout. Hopefully our 250 people having off will stimulate broader changes elsewhere.”

Cancelling Columbus Day is a symbolic gesture in its own right. On the one hand, it would be acknowledging that Christopher Columbus is not the national hero we want him to be. On the other hand, Columbus Day in Philadelphia has come to mean Italian-American Day, celebrating a longstanding and vital culture in our city,

In Philadelphia, where there are 25,000 city workers—the size, yes, of all of Sandusky—a day off might mean thousands of more votes cast, or maybe thousands more people to volunteer at poorly-staffed polling sites, to help people get to the polls, to spread the word about why they’re off—because there’s an election. And a move by City Hall could prompt other big companies to act in accordance—particularly for workers who are paid hourly and in shifts that make getting to the polls when they are open more difficult.

There is some interest in this locally: State Rep. Chris Rabb announced over the weekend he plans to introduce a bill in Harrisburg that would make the swap. But if the federal Republican response is any indication, that’s unlikely to pass our Republican-dominated state legislature.

Of course, cancelling Columbus Day is a symbolic gesture in its own right—one that is rife with Philly-style controversy. On the one hand, it would be acknowledging, like many jurisdictions around the country, that Christopher Columbus is not the national hero we want him to be. He did not “discover” the land on which thousands of indigenous people were already living; he showed up uninvited with a crew who raped, pillaged and brought death and disease to the land and its people.

About how to boost voter turnoutRead More

In Sandusky, Wobser says the city commissioners unanimously voted to make the holiday swap—and then heard from local Italian-Americans that they were not pleased. In the subsequent months, Sandusky has started to develop a relationship with Mordica, Italy, from where many Sandusky Italian families hail; they are on their way to becoming Sister Cities, and Sandusky is planning an Italian-American Festival to celebrate that connection. “We realized after we made the decision that we didn’t know enough about Italian immigration,” Wobser says. “This was a story of their American dream.”

It is a dream, this America. And how better to celebrate, as Italians or Indigenous People or immigrants or any of us, than by voting?

Photo Kārlis Dambrāns / Flickr