It’s rather amazing and quite telling on the state of affairs in Philadelphia, that no one in City Hall has yet broached the subject of firing Schools Superintendent William Hite. If there ever was a first-step solution to the slow-moving toxic iceberg hitting the public school system, it might be that. And overhaul the School Board while at it.

There is an uncomfortable sense, perhaps a sort of Philly-fied and culturally self-imposed standard, that this too will pass. An acceptance that the crisis festering throughout the city’s public school system will simply rectify itself, or that the largely poor residents and their children who rely on it for daily education, space, food, comfort and a guard against truancy will have no other choice but to deal with it. That has been, perhaps, the cruelest aspect of the ongoing saga of Philly’s perpetually dysfunctional and disregarded school system: that city officials, including the superintendent, have acted so casually and nonchalantly about the affair, moving mule-like in an uncaring bureaucratic stasis that telegraphs “just deal with it.”

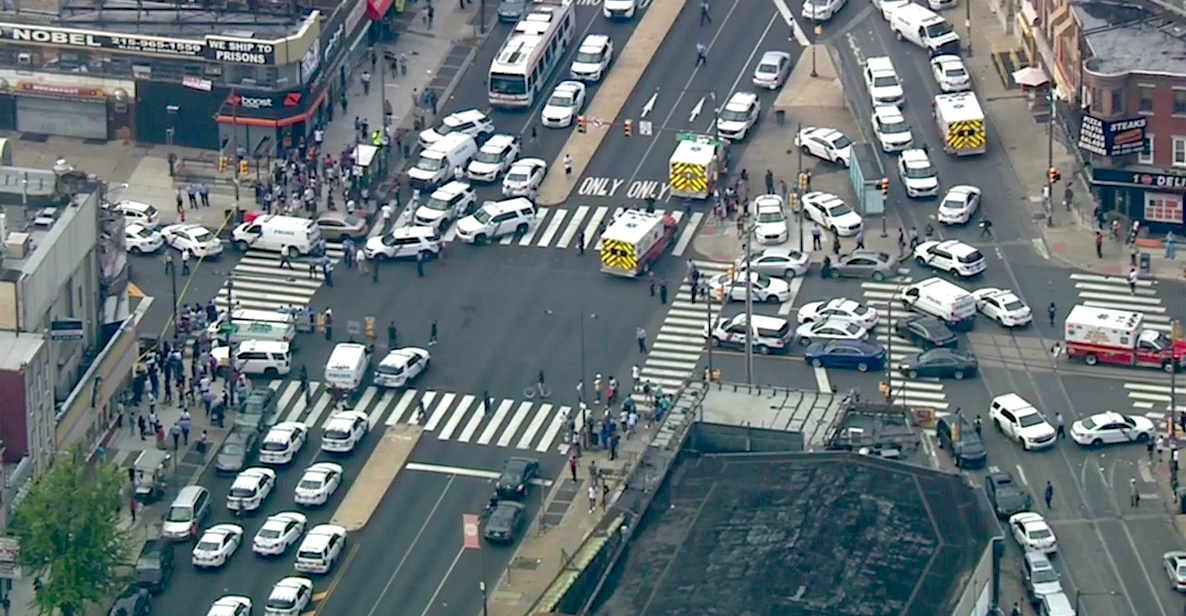

![]() That should be unacceptable when student health, outcomes and collective futures are at stake.

That should be unacceptable when student health, outcomes and collective futures are at stake.

And that gets to the root of the problem with the Philadelphia public school district: There are way too many low-income students in it, as much as 81 percent are in poverty. The school district itself releases barely user-friendly (and clearly inaccurate) data pointing to virtually all students are “CEP” or “Community Eligibility Provision” classified, meaning all Philly students are eligible for free breakfast and lunch. Now, that might raise alarm among the rest of us who really care about the condition of those students and would be moved to do something relatively fast and creative.

But to City Hall and the current superintendent, one could argue that it’s not registering in such a way to force a watershed moment. Philly decision makers would never admit it publicly, but the lack of urgent conversation and action suggests a subtle assertion that most Philadelphians should, ultimately, put up with it because it’s all they’ve got. The failure to set a radical tone exposes that, and it shows the true colors of those in charge. Hite, who hadn’t, up until now, really run a massive urban district fraught with the kind of pervasive poverty issues present in Philadelphia appears somewhat disconnected from that reality and only incremental when the news cycle hammers him. Philadelphia’s economically distressed parent-student population doesn’t have the kind of household income and powerful lobbying support that can break through that.

There’s no passion or anger on display from city officials on what impact, short or long term, the discovery of carcinogenic asbestos, lead and who knows what else is having on student health.

You see that even in the way the city and media respond to the now-regular announcement of one toxic school building closing after another—it’s now about six. There’s no passion or anger on display from city officials on what impact, short or long term, the discovery of carcinogenic asbestos, lead and who knows what else is having on student health.

The response is relatively boilerplate: “The School District of Philadelphia’s top priority remains to provide a healthy, safe and welcoming learning environment for all students and staff,” was the standard line from spokesperson Megan Lello.

We’d even expect that the city’s Public Health Department would, as a way to soothe public fears and instill confidence, activate district-wide screenings, particularly in the schools slated for closure. Yet, city Health Commissioner Thomas Farley—in a fashion similar to the PES oil refinery fiasco—chose to punt when asked recently about the agency’s role on WURD’s Reality Check, describing an “advisory capacity” as the school district sorted it out.

Insanely, that would seem like an obvious and rather immediate step: assessing how sick the kids would get from a situation like this … right? Yet, there’s no indication of a move in that direction. At this rate, we’ll only find out generations from now through data sets, tables and disease maps, and stupefied city officials who’ll all act like they don’t know where this started. In a way, “you can make the argument that this is criminal to have people coming in and out of school buildings and getting sick because of the environment”—that’s the way State Rep. Joanna McClinton described it on WURD’s Reality Check. “And it’s discriminatory. It’s very poor, very Black and Brown communities where this is happening.”

Because it’s Black, Brown and poor kids. They’re not White (let’s just admit that), they can’t vote, the turnout in the poorest precincts where they live isn’t motivated to turnout (or gets low-fi purged because they’re forced to move more), and their parents aren’t organized into any political threat large enough to petrify city electeds into fresh action. The current mayor, who slid very comfortably into a second term, didn’t face any challenge, so he’s under the assumption that—minus the noise—residents are fairly comfortable with the way things are being run on North Broad Street.

We know that’s not the case. And it’s not just the school buildings.

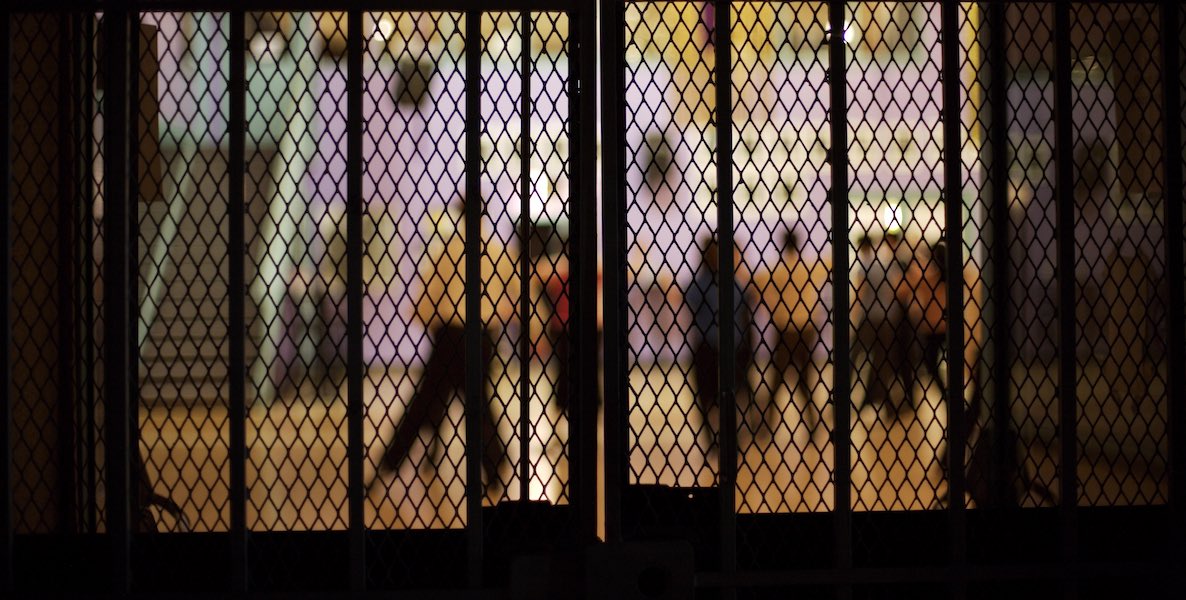

![]() There hasn’t been any real open discussion about the district’s failing performance. The on-time high school graduation rate for district students, while on the rise, is still just 72 percent—well below the national average of 84.6 percent, and behind peer big cities like New York, Los Angeles and Chicago. What’s happening with the lost 13 percent?

There hasn’t been any real open discussion about the district’s failing performance. The on-time high school graduation rate for district students, while on the rise, is still just 72 percent—well below the national average of 84.6 percent, and behind peer big cities like New York, Los Angeles and Chicago. What’s happening with the lost 13 percent?

And when we comb deeper, nearly 6 percent (as of 2017) didn’t finish 9th grade, with dropout rates at 7 percent (the national average is 5.7 percent)—and Black students representing nearly 60 percent of that group. The Philadelphia Education Research consortium finds in that same time period that Philly K-12 students are among the most “mobile”—or about a quarter are at the highest risk of moving around too much or altogether exiting a school. High rates of bullying and a city gripped in a violent crime epidemic places additional strain on a strained situation bursting at the seams.

That’s aggravating Philadelphia’s ridiculously high adult literacy rate—nearly a quarter of working-age adults in the city are functionally illiterate. Which also aggravates economic and labor participation indicators and, ultimately, keeps poverty high. Yet, according to the district’s own data, reading proficiency rates declined between 2012-2013 and 2017-2018—from 52 percent to 45 percent. Only 20 percent of students are mathematics proficient. So, ummm, what’s the plan for that? And, more importantly: Why isn’t anyone raising hell about that?

The current Mayor, who slid very comfortably into a second term, didn’t face any challenge, so he’s under the assumption that—minus the noise—residents are fairly comfortable with the way things are being run on North Broad Street.

At the very least, a safe and healthy learning space should be standard for all school kids. One wonders when the city’s internationally renowned academic institutions and others will step up to assist with that. Could City Council and the mayor, when negotiating with the building lobby about the 10-year tax abatement and other changes, have asked developers to pitch in on school building remediation or even new school building construction? Since abatements siphon some money away from schools, a deal could have been cut whereby developers donate remediation services or maybe repurpose existing buildings in exchange for “abatement credits.”

We see developers do that occasionally with universities, like what happened at Salisbury University in Maryland. Why not do it for K-12? And why not here? The condition of schools in any city are among the first things newcomers and new businesses look at when considering a move to a new town. If city leaders don’t care so much about student health and the moral dimensions of a failing system, they should care about the economic consequences of not acting fast.

When blasted for moving too slow on an urgent school fix, city leaders, as expected, point to budget challenges. They just can’t pay for all this, and the district itself might see a $700 million shortfall in the next two years. Yet, Philly is boasting a nearly $440 million surplus.

![]() While, yes, it’s certainly prudent not to dip too much into that honey pot out of an abundance of caution over future recessions, it’s not like residents weren’t telling City Hall to nix that tax abatement—and it doesn’t explain the billions either misspent or lost by the city in recent years, and money that could come from other places like the Parking Authority.

While, yes, it’s certainly prudent not to dip too much into that honey pot out of an abundance of caution over future recessions, it’s not like residents weren’t telling City Hall to nix that tax abatement—and it doesn’t explain the billions either misspent or lost by the city in recent years, and money that could come from other places like the Parking Authority.

There’s money all over Philly: It’s either sitting in Excel spreadsheets or the General Fund, where 65 percent of Beverage Tax revenue ($134.4 million) is just dormant, or in the endowment coffers of top Philadelphia universities that don’t pay taxes, but are not stepping up to help raise the stock of what could be their future college students.

Meanwhile, schools continue to close, classrooms are stuck in low performance and we don’t know how much the students are impacted by sick buildings. The asteroid keeps getting closer and there’s little accountability in sight, save an embarrassing press conference and a public forum full of angry, helpless families.

Looking for solutions to fix Philly’s schools? Here are some ideas we’ve written about:

- Philly parents need to step up for healthier schools. Here’s how.

- Hire more Black teachers, because they create positive impacts for Black students

- A startup guru turns his attention to pushing computer science education in Philly schools

Header photo by Owen Byrne via Flickr