It’s hard to believe now, but going out for dinner in Philadelphia circa the early ‘70s was a decidedly stuffy affair. Everything came under the stultifying rubric of “fine dining,” with tuxedoed waiters serving leathery steak and canned peas to nattily-attired diners. Into that milieu strode an artist in chef whites, a Peace Corps trainee-turned-antiwar protestor who wondered why food couldn’t be the thing to bring people together in the big, cold city.

Steve Poses was, arguably, Philly’s first hipster, influenced in equal measure by Julia Childs’ Mastering The Art of French Cooking and Jane Jacobs’ The Death and Life of American Cities. His groundbreaking restaurants—among them, Frog and The Commissary—democratized dining, yes, but also advanced a notion of real democracy in action.

“Jacobs wrote about the neighborhood candy store, how these anonymous people in these big buildings would come together in these candy stores, and that’s how community would initially form,” Poses, 71 now, recalls. “I just thought, ‘Well, restaurants could do that with better food.’ That was the driving force behind the first Frog in 1973 and the Commissary. So I’m very in tune with the idea that restaurants can play a positive social role.”

Poses is no ideologue. He describes himself as a centrist, because “the center is where the solutions are.” His objection to Trump is not based on issues or orthodoxy. It comes from the dissolution he sees all around him of the guiding philosophy of his life.

Poses’ Commissary, for instance, on 17th and Sansom, featured a menu today’s foodies would gush over (sushi before anyone had heard of it), but in a cafeteria setting. There were communal dining tables long before the term had entered the lexicon; it was a place—not unlike sports arenas—where Philadelphians would go to escape big city isolation. We’re all in this together, Poses would think, gazing with pride upon students breaking bread alongside lawyers alongside factory workers.

Well, he’s at it again. After the election of Donald Trump, this veteran of the counterculture found himself in his 2,400 square foot South Philly penthouse, screaming at his TV day after day. His wife, Christina Sterner, is the CEO of their Frog Commissary Catering business; Poses, meantime, had been going through the stages of political grief ever since November of 2016. He was stunned, depressed, angry and, finally…determined to once again make a difference.

![]()

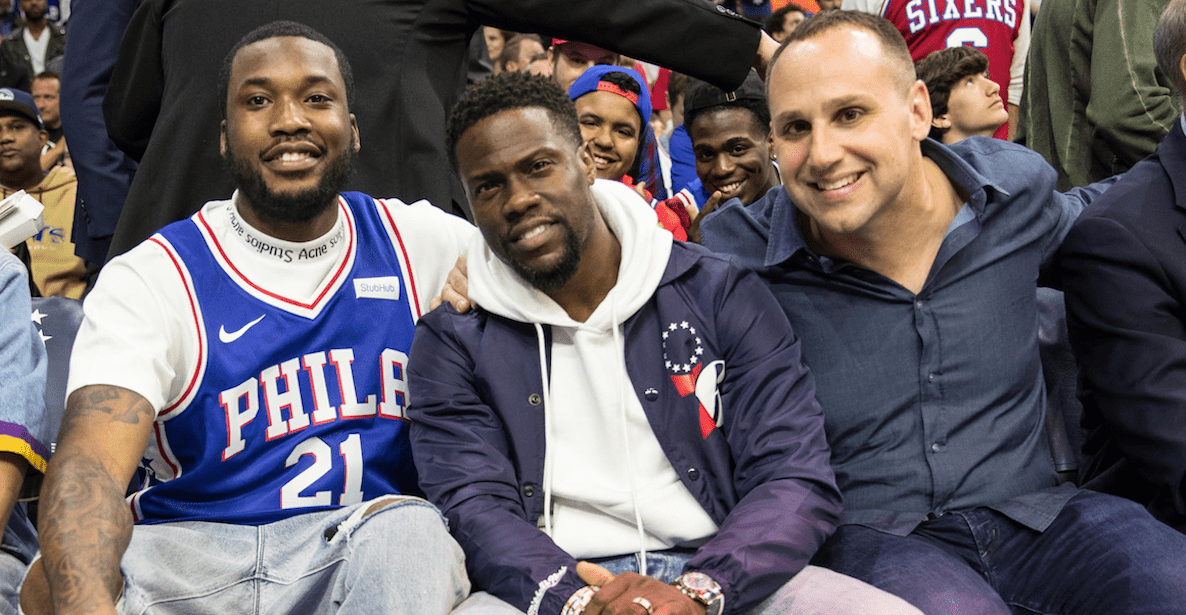

Next month, at The Franklin Institute, he’ll host The Blue Plate Special, a fundraiser and political pep rally designed to turn Pennsylvania blue. (He is formally announcing the event today.) It will include dancing, the cooking of some 50 area chefs (recruited and curated by former Inquirer food columnist Rick Nichols), and, he hopes, every Southeastern PA Democratic candidate, plus Governor Wolf, Senator Casey and Lieutenant Governor candidate John Fetterman. “Hungry for Change? Put Your Money Where Your Mouth Is” is the event’s tagline, in keeping with Poses’ belief that the way to a better world—and a better politics—is through our stomachs.

Proceeds will benefit the PA Blue Victory Fund, the organization Poses recently founded to fund candidates, grassroots organizations and strategies to build a war chest for 2020 and beyond. Poses and his family seeded the fund with $150,000, with a goal of raising $500,000 for the midterm. “We’re late for the midterm, but early for 2020,” he says.

So what got Poses to shut the TV and get off that couch? Last fall, Steven Springer, a friend with whom Poses volunteered on the Obama ’08 campaign, badgered him into attending a meeting of concerned citizens in a Rittenhouse Square apartment. There, he heard from Jamie Perrapato, a lawyer who, after 2008, said goodbye to her practice in order to found Turn PA Blue, an organization dedicated to flipping the state legislature by training grassroots groups and volunteers to support Democratic candidates in Southeastern Pennsylvania.

“I consider myself an informed citizen, but I had no idea just how red Pennsylvania had become,” Poses recalls. “Something’s wrong. Democrats have an 800,000 voter registration advantage, but the Senate is 34 Republicans and 16 Democrats, and the House is 120 to 83. And Congress is 12 to 6. Jamie was bootstrapping this movement, so a few of us wrote her $500 checks.”

Poses kept peppering Perrapato with questions, calling their exchanges a “master class” in how elections are run and won. The more Poses thought about it, the more he felt something bolder was needed. “I like to say there’s a fine line between audacious and hubris,” he says. That’s when he came up with the idea of funding on a grander scale the type of on-the-ground blocking and tackling Perrapato was talking about. One of his first calls was to former Mayor and Governor Ed Rendell. “I’ve fed you plenty over the years,” Poses told him. Rendell, who responds to great meals like a lion when a thorn is removed from his paw, quickly signed on to be the showcase event’s Honorary Executive Chef.

“I worked my whole life to create a world for my son that I could feel good about,” Poses says. “Now what kind of legacy am I leaving him? Okay, maybe we can’t change today’s economics, with all the factors disrupting our world. But what about the values we’re leaving the next generation?”

“That night I first met Jamie, we were in an apartment on what might be the richest street in the Commonwealth,” Poses says. “And everyone had been doing what I was doing. Just yelling at our TVs. What happens traditionally in politics is you get asked to give by the same people—I get all these Tom Perez emails everyday—and you ask the same people. The goal has to be to increase the size of the pie.”

And food, he’s betting, could do that. “There’s a huge pool of untapped money out there,” Poses says. “After 2016, so many people said, ‘I’m upset with Trump,’ but they didn’t know what to do. Progressives were giving to Planned Parenthood or national redistricting. They’re all black holes. You have no idea where your money is going. The assumption here is this is your own backyard, you have a right to know where your money is going. We’re giving them a convenient way to invest smartly, because these grassroots organizations, which are all under-resourced, have the potential to be the fabric that sustains us from election to election.”

![]() Industries don’t get disrupted from within; it will likely take creative thinkers from outside politics to bring change to how things have always been done. Too often, getting engaged politically is seen as akin to having to eat your vegetables. Poses, however, knows the importance of spectacle. “This is a dance party,” he says. “I don’t want a lot of ponderous speeches. It’s a pep rally with great food. I always saw restaurants as giving people a chance to feel like they’re part of a community—they’re not isolated individuals, stuck and alone. This is a natural extension of that.”

Industries don’t get disrupted from within; it will likely take creative thinkers from outside politics to bring change to how things have always been done. Too often, getting engaged politically is seen as akin to having to eat your vegetables. Poses, however, knows the importance of spectacle. “This is a dance party,” he says. “I don’t want a lot of ponderous speeches. It’s a pep rally with great food. I always saw restaurants as giving people a chance to feel like they’re part of a community—they’re not isolated individuals, stuck and alone. This is a natural extension of that.”

Poses is no ideologue. His history is as a civic innovator—he founded the Center City Proprietors Association along with Meryl Levitz in 1979—not a political player. He describes himself as a centrist, because “the center is where the solutions are.” His objection to Trump is not based on issues or orthodoxy. It comes from the dissolution he sees all around him of the guiding philosophy of his life.

“I remember reading Marshall McLuhan’s The Media Is The Message,” he says. “We used to have three TV channels and everybody met around them. Now we don’t have community anymore. We don’t have that neighborhood candy store anymore. The world exploded from globalization and technology and people are scared. And when people are scared, they pick despots. We have failed to respond to the real fears of people who are dislocated in the world psychologically, politically, and economically. So they turned to Trump because he has easy answers and inflames them.”

“I consider myself an informed citizen, but I had no idea just how red Pennsylvania had become,” Poses recalls. “Something’s wrong. Democrats have an 800,000 voter registration advantage, but the Senate is 34 Republicans and 16 Democrats, and the House is 120 to 83. And Congress is 12 to 6.”

At the Blue Plate Special’s VIP party, Poses will cook alongside his son, Noah, who is chef de cuisine at, of all places, Washington, D.C.’s Watergate Hotel. It will be the first time they’ve cooked together; for Poses, it says something about the intergenerational imperative of this cultural moment. Back in those halcyon days when Poses was marching against the war in Vietnam, a rallying cry was the personal is the political. Well, this is personal to Steve Poses. “I worked my whole life to create a world for my son that I could feel good about,” he says. “Now what kind of legacy am I leaving him? Okay, maybe we can’t change today’s economics, with all the factors disrupting our world. But what about the values we’re leaving the next generation?”

So now he’s hard at work again, rising at 6 am and going till 11 at night, putting in restaurateur hours. When I ask why, this icon who saw that the how we eat could be a political act long before that connection became a part of the zeitgeist, returns to a certain body part—the filling of which has been his lifelong passion: “We have to try and change things,” Steve Poses says. “I just can’t stomach the indecency.”