“Roosevelt Boulevard was once referred to as one of the most dangerous stretches of highway in the nation,” reads a press release from the Philadelphia Parking Authority, May 12, 2021.

The past tense is important here. To understand why, let’s step back to 2013, when the danger on the Boulevard was very much in the present.

Samara Banks was 27 years old and her life had already been marked by tragedy. Her mother died of a staph infection when Samara was 20. Her father, Darrell Banks, was shot and killed by plainclothes officers that January. He was walking home from his grandson’s birthday party. Officers said he pulled a gun when they approached him. It was a phone.

Samara, as the oldest, was left to care for four siblings. No easy feat since she was a single mother with four boys of her own. “She loved children,” says her aunt, Latanya Byrd. “She worked at a childcare center. She was always doing things with kids.”

On July 16, Banks, her four children and her half-sister Laporcha Jones were walking home from an aunt’s house where they’d spent the day swimming. The evening was cool and they decided to walk home, which involved crossing an intersection of Roosevelt Boulevard where there was no traffic light or crosswalk.

The young mother looked the role of caregiver. Her seven-month-old son, Saa’mir, was strapped to her body. She was pushing Saa’sean, her 23-month-old, in a stroller. Saa’deem, her four-year-old, grasped her free hand. Laporcha (14) had taken the hand of Samara’s oldest, Saa’yon, (5) as they hustled across the street.

“It was at, like, 2nd and Roosevelt,” Byrd remembers, stumbling a bit on the exact location. “But, it’s called Banks’ Way now.”

The driver who struck Samara Banks and her children was drag racing down the Boulevard. Blowing through light after light, the other racers began pulling back. One souped-up Audi did not.

“Once they passed Masher,” Byrd continues, “[the drivers] started seeing debris. The other drivers [said they] thought he went through a bunch of trash.”

Byrd stops here in the retelling, waiting for the force of those words to sink in.

A bunch of trash.

Banks and Saa’mir, her infant, died instantly. Saa’sean, in the stroller, died later that night. Saa’deem, age four, died early the next morning. Saa’yon, age five, made it across the street. He was holding his auntie’s hand when he turned back to witness the horrific aftermath.

Today, Byrd is a fierce advocate for safety measures along Roosevelt Boulevard. “I do it for Samara and the kids,” she says, “I know they didn’t die in vain.”

Speed kills. Speed cameras save.

A few months ago, I wrote a story about the city’s involvement in Vision Zero — an international initiative to eliminate traffic-related fatalities. What reams and years of data collection tells us is this: Speed kills. Street design matters. Calming measures like speed bumps and roundabouts matter. Pedestrian visibility matters, but they are all in service to disrupting a single factor: speed.

And out of all the varied attempts to bring vehicle speeds down, one stands above the rest for its efficacy: automated speed cameras.

It would seem a no-brainer, then, to simply line dangerous roadways like Roosevelt Boulevard with speed cameras. No-brainers in government, however, often seem a bar too high.

The City of Philadelphia cannot install cameras everywhere, of its own power. Corinne O’Connor, Deputy Director, Philadelphia Parking Authority explains Roosevelt Boulevard is a state highway; its speed cameras are part of Pennsylvania’s Automated Speed Enforcement Pilot Program, enacted through state legislation.

“Everytime we want to add a camera, it has to go back to PennDOT for approval,” O’Connor says. “We have to send a letter to the Secretary of Transportation, and they have to send a letter back with a notice to proceed.”

“Correct me if I’m wrong, Corinne,” interjects PPA Executive Director Rich Lazer, the city’s former deputy mayor for labor, “it’s mostly based around the violation. [Speeding tickets] are moving violations, not parking violations.” In 2019, the Boulevard saw 374 crashes: 47 speed-related; 27 of them fatal or nearly fatal.

The results have been dramatic.

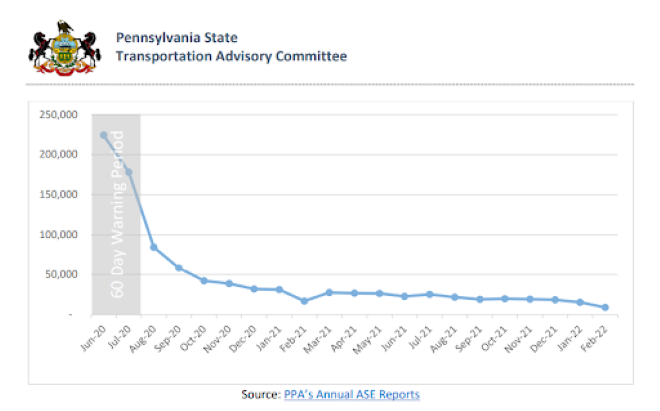

Eight cameras first went onto Roosevelt in June 2020. There was a grace period of 60 days where you were informed that a speeding violation would have been issued. On August 1, those who chose to speed along the Boulevard began receiving citations of up to $150 each.

“We had to figure out how many tickets you could get at once,” O’Connor says. “If you got on at 9th Street and sped all the way to South Hampton, are you going to get 10 tickets? We had to put a limit of three tickets every 30 minutes.”

Lazer stepped in again to stress that the goal of the program is changing driver behavior. “It’s not a point system like when you get pulled over by an officer. It doesn’t go on your record. It’s just citations.”

Points or no, those automated tickets bite hard into your wallet. That is what changed behavior. Within one year, the Parking Authority caps-yelled on their website:

PPA’S SPEED CAMERAS REDUCED SPEEDING ON ROOSEVELT BLVD BY 93% IN FIRST 9 MONTHS

– 12 May 2021

This dramatic result — a 36 percent reduction in Boulevard crashes from 2019 to 2021, compared to a mere 6 percent reduction in the city as a whole — has since evened out as motorists have adjusted (some drivers have taken to concealing their license plates from cameras), despite two additional intersections being added to the program.

Nonetheless, the cameras have remained an unblinking bulwark against speeding.

Byrd notices the difference. “Honestly, I take Roosevelt Boulevard,” she says. “It’s a really nice ride when you’re doing the speed limit.”

There is another benefit to the cameras, which Lazer points out to me several times. “The revenue from the citations goes back to the state,” he says. “Then they give those out as grants to help with transit safety.”

How much are we talking here? The total revenue from Fiscal Year 2023 amounted to almost $18 million. $13 million dollars are coming back to the City (much of it to Roosevelt Boulevard) for things like intersection redesign, upgrades to traffic signals, and curb extensions.

Solutions are not always permanent

The fly in the ointment of all this encouraging progress, however, is that the Boulevard’s camera program is not permanent. It is a pilot program. One that requires us to return to Harrisburg, bowl in hand, to ask, Please, sir, I want some more.

In Philly, we might be addicted to pilot programs. Everything from Universal Income pilots to an extra trash can for your house (a … Philacan). Did something work well in another city? Let’s do a two-year feasibility study and a five-year pilot program here. At times this can feel like a version of the Philly Shrug — a parallel noncommitment to policies that can actually make real change.

Lazer says it’s just par for the course. Slow and methodical and teeth-grindingly cautious is simply how things are done in big cities, he says. But the PPA issued an ominous statement in its most recent report:

The sunset time of the speed program is quickly approaching [12/23] … it is more important than ever that the pilot program be extended or made permanent.

Ring the Pilot Program Czar at City Hall then, and let them know this pilot is a blazing success. It saves lives, it’s a financial boon for the city; we must make sure the administration advocates for its continuance.

Alas, we have no Pilot Program Czar, no one in charge of alerting government officials or the public when a program the City is trying out is set to expire. Departments and agencies are left to advocate largely for themselves, oftentimes depending on the help of regular citizens like Latanya Byrd.

“We went to Harrisburg,” she says, “it was one of those busy days where everyone had to report in-person. We got a chance to talk to state reps and senators and tell them how important it is to make this program permanent and allow us to expand the cameras throughout the city.”

Byrd’s civic activism is inspiring. And Lazer believes the program will be extended come December. “I feel very positive. Our data was very well received by Harrisburg on both sides,” he says. “I’m confident the legislation will be done this fall.”

But when a city is constantly grasping for things that actually make our lives better and safer, shouldn’t someone in the Mayor’s Office be keeping a vigilant eye on all these pilots? Surely there are ideas out there like the speed cameras worth holding onto.

“There is no single manager who oversees pilot programs,” wrote Charlotte Merrick, deputy communications director, Office of the Mayor.

Adds Sarah Peterson, the City’s communications director, “The determination about whether a program should be continued or advocated for is made by subject matter experts who are in a position to evaluate the evidence, in partnership with City leadership.” (Peterson’s use of the passive voice doesn’t exactly impart confidence.)

For speed cameras on the Boulevard, PPA directors and citizens like Byrd realize the importance of taking bold action amidst the normally lugubrious pace of a city our size.

“It’s hard for me,” she says. “When I’m in a car and I see someone walking with a stroller and kids, I’m just so nervous. This is about preventing the next family from going through what my family has gone through.”

![]() MORE ON TRAFFIC SAFETY FROM THE CITIZEN

MORE ON TRAFFIC SAFETY FROM THE CITIZEN