In the fourth verse of Sam Cooke’s seminal civil-rights anthem, “A Change is Gonna Come,” he passionately croons: “There been times that I thought I couldn’t last for long, but now I think I’m able to carry on.”

Cooke so eloquently captured the pain, hope and resilience of what it means to aspire for change that it reverberated with Civil Rights activists and advocates of the 1960s and 1970s and can still be felt today.

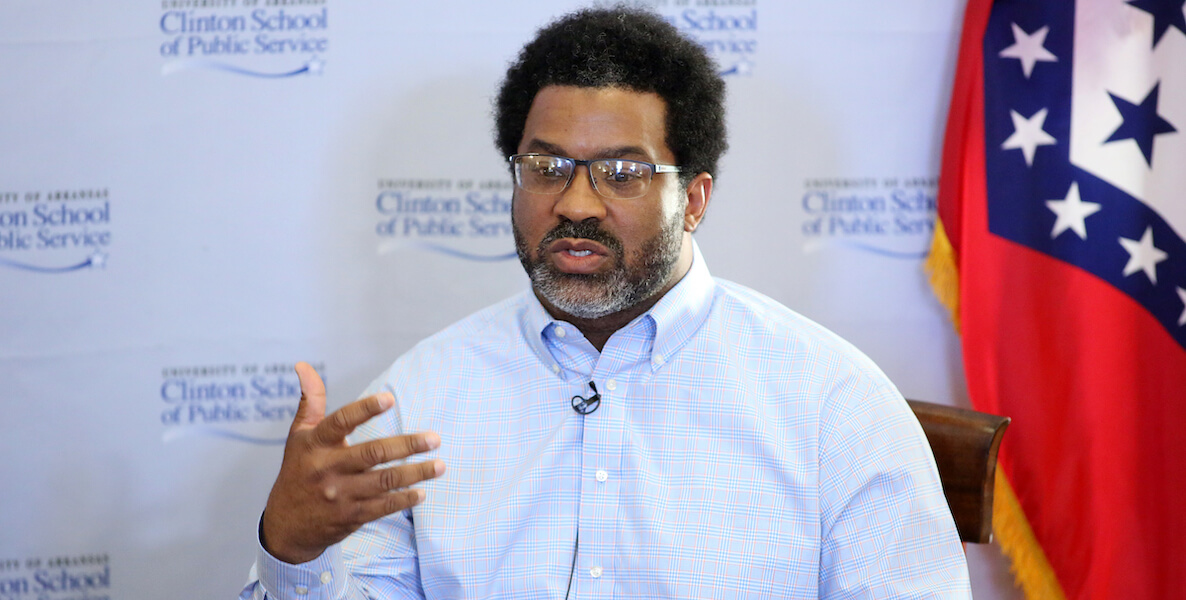

It’s that same sentiment that journalist and former Inquirer features reporter Sofiya Ballin evokes in describing the latest installment of her acclaimed Black History Untold series, “Revolution.”

“The central message is to show that black people are never alone in the fight for their civil and human rights and we’re all fighting together,” says Ballin.

![]() “Revolution” premieres on Tuesday at the Museum of the American Revolution (MoAR) and features 15 film vignettes from local, national and global voices.

“Revolution” premieres on Tuesday at the Museum of the American Revolution (MoAR) and features 15 film vignettes from local, national and global voices.

The installation explores the idea of resistance, resilience and revolution in the context of black history—three R’s that have incited change on a global scale.

Immediately after the film, guests are invited to attend a panel discussion with several of the film’s participants, including Jamira Burley, named to Forbes Magazine’s “30 under 30” for her community activism, and Mike Africa Jr., whose parents were part of the MOVE 9.

We caught up with Ballin to discuss “Revolution,” the intentionality of debuting her latest installment at MoAR and her thoughts on black revolutionism in Philly and beyond.

Jared Michael Lowe: This is the fifth installment of Black History Untold and your third since going independent from the Inquirer. How is this one different?

Sofiya Ballin: When I left the Inquirer in the fall of 2017, having worked on developing two successful Black History Untold projects, What I Wish I Knew and Joy, I knew that the project was bigger than me and needed to be independent.

I consider myself a journalist, first, and although I’ve been doing visual storytelling for two years now, it’s still new to me.

There was no way that some of these stories featured in this project and others could be solely textual. We need to hear their voices, see their eyes.

At this point, the project has collected over 160 stories, and there are so many interviews where I’ve watched people cry talking about their history and I don’t think people realize the power in talking about where you are from.

I’ve released three installments: Future, Herstory, and “Untold,” a collaboration with the Brooklyn Nets.

In “Revolution,” we look at the past and our current history and what it means to take action and inspire real change.

Yet, this project is not just me. I worked with an incredible team of talented individuals. They include director of photography and editor Emmanuel Afolabi, camera operator and sound mixer Lou Peluyera, set designer Keturah Benson and production assistant Akilah Grant-Sullivan.

I want the installation to remind people that we’ve been through this before and that there are people who are continuing to fight, that though times are different, the stakes are still high.

JML: What made you want to center it on black revolution?

SB: I’m aware of the political climate that we’re currently in and there’s attacks on so many who have been marginalized—from the overall language used from the powers that be to legislation that impedes people’s basic rights.

I want the installation to remind people that we’ve been through this before and that there are people who are continuing to fight, that though times are different, the stakes are still high. And, to show resilience—that there were people who came before us and saw value in us being here and were willing to risk their lives for a generation that they dreamt about.

In return, I ask, are we, currently and collectively, willing to do the same?

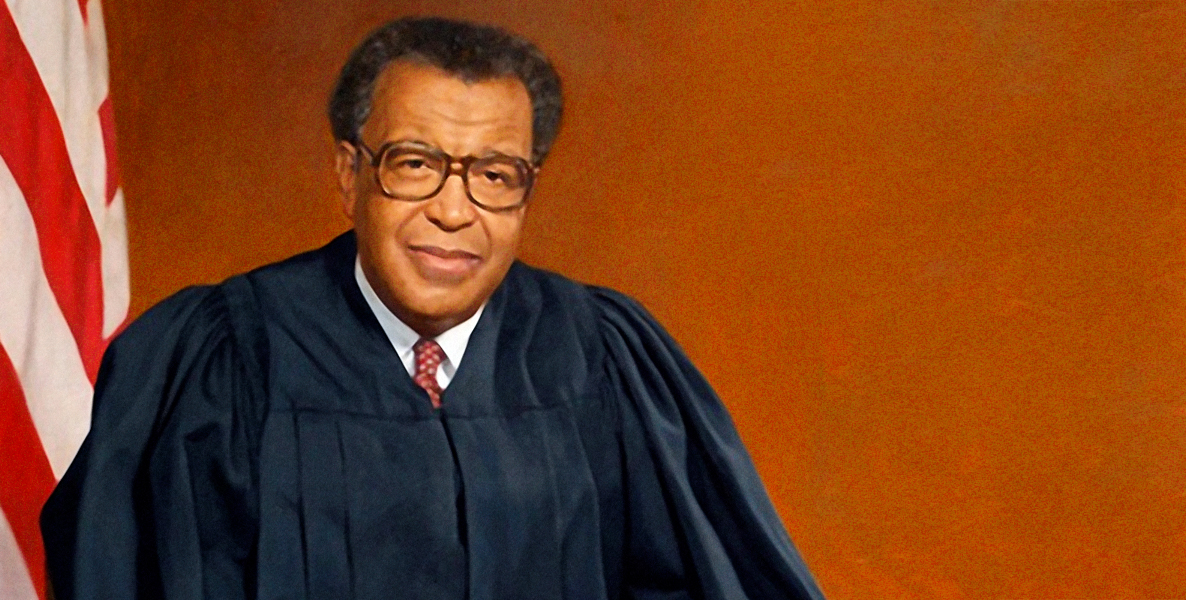

![]() JML: Having the installation premiere at MoAR seems very intentional. Can you talk more about its significance there?

JML: Having the installation premiere at MoAR seems very intentional. Can you talk more about its significance there?

SB: It is! Last fall, I was invited by MoAR to give a lecture on Black History Untold. It was an hour-long talk and I ended by asking those who attended, Who was American? And what is patriotism? I ended on that note because I thought about the magnitude of having a discussion like that in that space. I’ve heard from several people that the space showcases a particular kind of revolutionism that is exclusionary of others.

So, when the museum approached me about the installation, I wanted to critically tackle what it means to be a patriot and revolutionary, because so often black people are excluded from the conversation.

History has shown that when black people are revolutionary or do revolutionary acts, we’re depicted as radicals or criminals. Take Huey P. Newton or even Colin Kaepernick and Bree Newsome— there’s a difference in how they are portrayed versus white revolutionists.

JML: What have you found inspiring while compiling interviews for the installation?

SB: That there’s sacrifice and a sense of love in being revolutionary. That in order to have a revolution, you need to sacrifice your livelihood for change and for a generation you may never know or meet.

Particularly with black people, it’s to show that we were never alone in the fight for our civil and human rights. That we’re all fighting for the same thing, against systemic oppression, supremacy, imperialism and more, and that it unites us across cultures, continents and through time.

JML: Philadelphia has a rich history and deep connection to revolutionism. How much of the city is inserted in the installation?

SB: Philly is felt throughout the installation. There are a lot of native voices included like Marc Lamont Hill, Jamira Burley and Mike Africa Jr., as well as national voices like Zellie Imani. There are so many inspiring and critical local voices and I was able to tap them for this project.

Having worked as a reporter for the Inquirer, I had the opportunity to meet and interview several artists and activists, and they don’t mince words and lend their support ,whether financially or physically, to support societal causes. I’m always inspired by that.

“The central message is to show that Black people are never alone in the fight for their civil and human rights and we’re all fighting together,” says Ballin.

JML: How do you see the installation as an overall form of black expressionism?

SB: I believe it pushes the envelope on what it means to be black and revolutionary. I believe it speaks to those truths of what it means to be both, the risks, the dangers and the tribulations that are associated with it, but also its beauty. Nothing changes unless you change the way people think and feel about other people, and a lot of that comes with storytelling.

JML: It seems like more and more doors are opening up for people of color and intersectional creatives to showcase these kinds of stories in various formats.

![]() SB: Yes, and more importantly people and institutions are putting money and capital behind these kinds of stories. It allows other media-makers, creators and activists to create and hold space to showcase what is going on in our society. It also is an opportunity for places like MoAR to open their doors to a wide community and say “you belong here.”

SB: Yes, and more importantly people and institutions are putting money and capital behind these kinds of stories. It allows other media-makers, creators and activists to create and hold space to showcase what is going on in our society. It also is an opportunity for places like MoAR to open their doors to a wide community and say “you belong here.”

JML: What can people expect once the lights dim and the film portion of the installation begins?

SB: That there are so many layers to it. The film is raw, informational and emotional. I interviewed a man who was exonerated after spending over 20 years in prison for a crime he didn’t commit. It’s one thing to talk about mass incarceration; it’s another when you hear the story of someone who was convicted of a crime that they didn’t do and they talk about all the time and opportunities they missed and how they plan to move forward.

I hope people leave with a sense of passion and pride. Black people have fought so hard for seats at tables or have constructed their own, and I hope the installation inspires people to feel empowered and lead with action.

Interview has been edited and condensed.

History After Hours: Black History Untold takes place Tuesday, February 11, from 5–8:30pm, at the Museum of the American Revolution, 101 South 3rd Street. Tickets are $10. More details here.