![]() As the Overton window shifts to center on looting and the burning or destruction of property; as the President chastises governors, calls for looters to be shot or for “vicious dogs” to be trained on protesting American citizens; as the media continues to preclude the immediate history of anti-black police brutality and violence in their current coverage of this insurrection; please remember why we are here.

As the Overton window shifts to center on looting and the burning or destruction of property; as the President chastises governors, calls for looters to be shot or for “vicious dogs” to be trained on protesting American citizens; as the media continues to preclude the immediate history of anti-black police brutality and violence in their current coverage of this insurrection; please remember why we are here.

We are here because Ahmaud Arbery was hunted and murdered like an animal; we are here because Breonna Taylor was murdered while she slept; we are here because Minneapolis police officers murdered George Floyd.

America is burning because black America is dying.

More to the point: Black America is dying slowly. We are dying a slow suffocating death. That is what it means to be black in these United States. That is what it has meant since so many of our ancestors drew their last breaths in the bellies of slave ships crossing the Atlantic. We died on the way here. And those deaths were rarely quick and never merciful.

The slow death is also what Covid-19 offers 13 percent of the entire African American population. One in every 2,000 African Americans have died slowly from Covid-19. We, who only make up 13 percent of this nation’s citizens, know the slow death well. It is a part of our history in this nation.

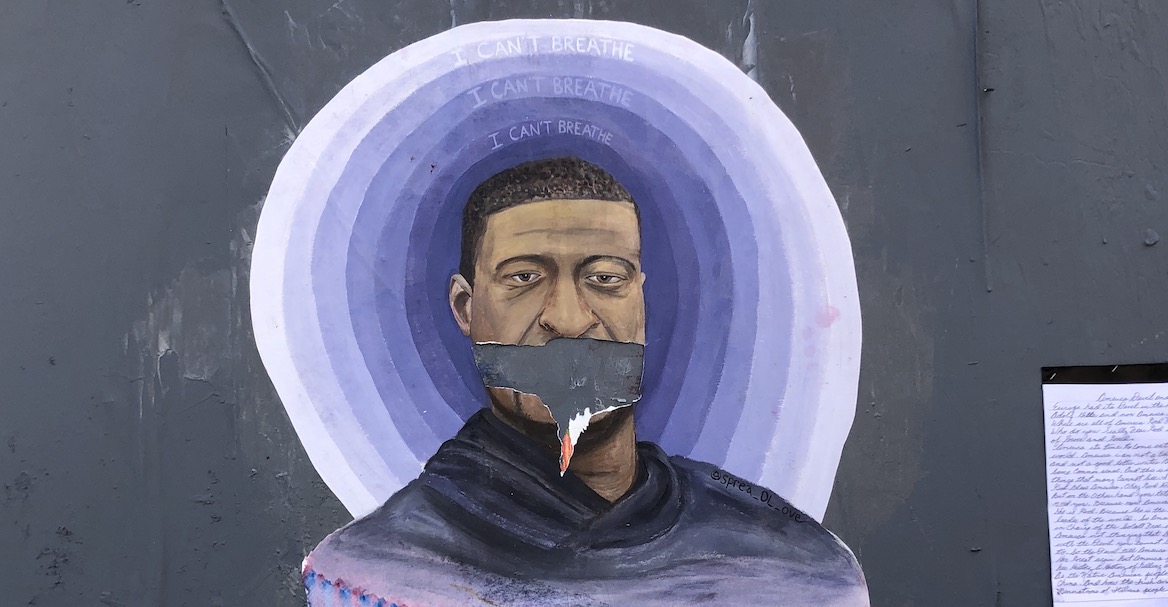

For many of us, the nearly nine-minute video of a smirking police officer knee-choking the last breaths from George Floyd, was a sickening reflection of our lived reality.

Enslavement, murder, theft and destruction, all in the name of anti-black racism and/or white supremacy; all in the name of American capitalism. In this country, death always seems to be black and the data tells us that this feeling—the collective feeling of a slow excruciating death, is, as my mom might say: more than a notion.

![]() Death doesn’t come to us all equally. In America, death is disparate and in black America, death is slow.

Death doesn’t come to us all equally. In America, death is disparate and in black America, death is slow.

The black mortal disparity manifests in every socio-medical enclave of our society: cancer, lung disease, kidney disease, heart disease and overall life expectancy.

We have higher infant mortality rates; higher maternal mortality rates; and black children (ages 5-11) have the highest suicide rate. When Rodney King died, I wrote that death was the “new black.” I was wrong.

Racially disparate death has been with us since we have been here. And in aggregate, all of this death by whatever means accessible, is slow. Black death is slow in that each excruciating iteration of it eats away at the heart of our collective community.

Natasha McKenna drew her last breath ‘in police custody’. Sandra Bland drew her last breath ‘in police custody’. McKenna’s last breaths were drawn under brutal duress from law enforcement. She was wrestled, beaten and tasered to death. We don’t really know or understand exactly how Sandra Bland drew her last breaths. After a traffic stop, she was arrested and later she was found hanged in the Waller County, Texas jail. Her death—“in police custody”—was ruled a suicide.

Breonna Taylor was murdered—shot eight times—in her sleep. Louisville law enforcement officers who shot her used a no-knock warrant to enter her home in the middle of the night in search of someone who was already in “police custody.” For most of us, dying in our sleep may seem to be the most merciful way to die. But for Breonna Taylor’s family, for her community, for her partner, her death is slow. It is as slow as the machinery of justice for those responsible for her murder who all remain un-charged.

The slow death is what anti-black policing has always delivered in/to our community even when those murders were quick. Police murdered Tamir Rice within seconds of coming onto the scene. They murdered him quickly; but his death was slow. It is slow for his mother, Samaria Rice, who continues to work through the Tamir Rice Afrocentric Cultural Center. His death is slow for his family and for his community. It is, in effect, endless. How many times was the video of the Tamir Rice’s murder played in the American media?

Dying a slow endless death is the opposite of immortality. It is an immortal mortality within which our community remains ensnared. We keep dying. We keep protesting. We keep fighting for change. We keep dying.

Some of this endlessness is instantiated by the ways in which black death is transformed into media spectacle. In some ways, America needed the video of George Floyd’s slow murder in order to grasp the heinous inhumanity with which black folks are policed on a regular basis.

But the video had a different effect on much of the African-American community. For many of us, the nearly nine-minute video of a smirking police officer knee-choking the last breaths from George Floyd, was a sickening reflection of our lived reality.

America’s knee is on our neck. We can’t breathe.

The nearly nine-minute video is a marker for the slow genocide of black people in America. That a nearly nine-minute video can encapsulate our anguish—some semblance of our pain—excavates the irony of our endless mortality. They can kill us quickly, but our deaths are slow. The slow death has been creeping into and through our community’s entire existence since the beginning of this American experiment.

Dying a slow endless death is the opposite of immortality. It is an immortal mortality within which our community remains ensnared. We keep dying. We keep protesting. We keep fighting for change. We keep dying. We keep fighting for justice, by all means necessary. We keep dying.

This cycle will continue to continue. So far—in this nation’s history—our pain, our protest and even our incremental influence on policy and policing have not been enough to unravel the knotted history of white supremacy and American democracy. And we keep dying, slowly.

James Peterson is a writer, educator and consultant. He will author The Citizen’s new Color of Coronavirus series, and is a host of “Tonight on WURD,” a nightly news program on WURD, Philadelphia’s only independently Black-owned radio network.

Header photo courtesy Saundi Wilson / Flickr