A few weeks ago, I had the honor of participating in and contributing at the 2016 Summit on Teacher Diversity at the US Department of Education. Friday, I was in our state’s capitol to provide feedback about Pennsylvania’s Equity (ESSA) plan, soon to be submitted to the US Department of Education.

And, last weekend, The Fellowship held its final Black Male Educators Convening (BMEC) of the school year to celebrate ten exceptional black male educators in the Philadelphia region. These experiences continue to steel my resolve to mentor new and aspiring male educators of color.

In all of these spaces, I had the opportunity to listen, learn, contribute, and, most importantly, affirm our collective experiences as men of color in the nation building occupation of teaching and leading schools and districts.

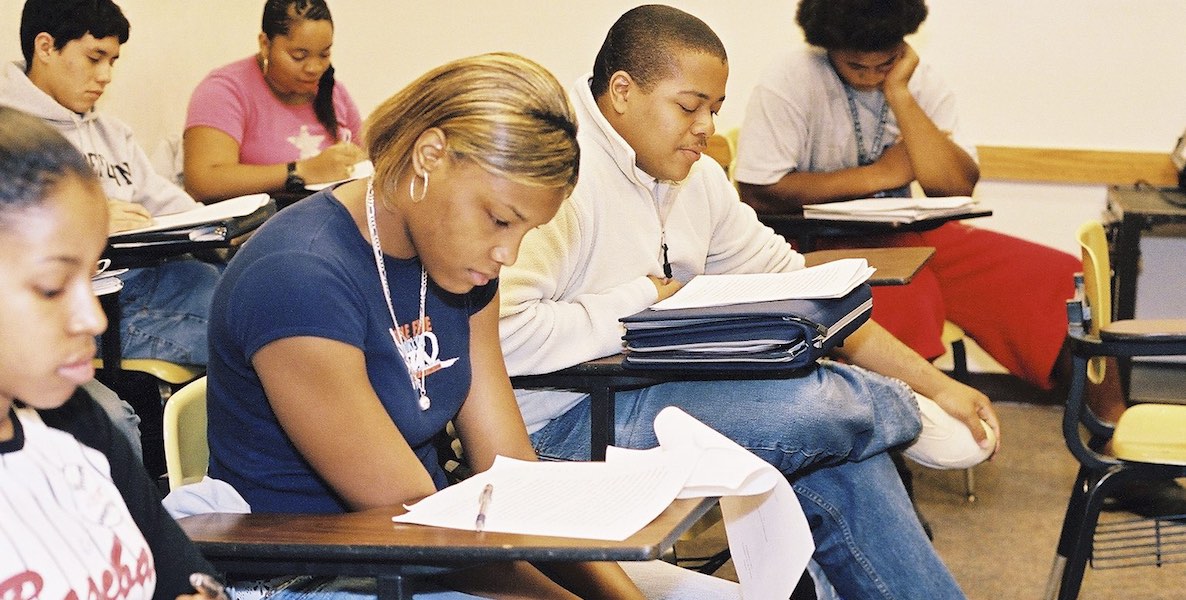

Black men make up less than 2 percent of the teachers in our country. Philadelphia has 4.5 percent. By contrast, more than half of the students in Philadelphia’s public schools are of African descent.

These experiences caused me to reflect on conversations I have had over the years with my colleagues at the “black male teacher water cooler.” Having been a part of these spaces that were focusing on male educators of color caused me to think about the circumstances that led me to my career in education that began in 1993.

Becoming an educator was the furthest thing on my mind while I was in college, despite having a roommate majoring in Elementary Education and having a mother who served our community as a teacher and, what I would call, a Freedom Fighter. The reasons are many, but one of the main reasons I believe I had never previously considered becoming an educator was that I simply was not asked until 1993 to consider such a powerfully impacting career in nation building. Although I had a deep commitment to fighting for social justice issues, I didn’t realize that one of the best ways to do so was in the classroom.

So, that got me thinking about the recruitment of diverse teachers—especially black men. As a current principal, here are just some of the reasons I believe it is so important to directly ask more blacks to jump into this nation building work called teaching.

(1) The Shift: A change in public education is occurring. More and more students of color are becoming a part of the public education system, and the people who serve them should at least be a larger part of the teaching force. Too often, students go through 12 years of public schooling while having very few teachers of color. To have a black male teacher is a very rare experience. I was blessed to have three.

Black men make up less than 2 percent of the teachers in our country. Philadelphia has 4.5 percent. If you remove the gym teachers, that percentage drops even further. By contrast, for example, more than half of the students in Philadelphia’s public schools are of African descent. And, today, there are almost 35,000 (out of 130,000 total students) black male students in the Philadelphia school district (excluding charters, where 66 percent of the students are boys of color).

(2) Windows and Mirrors: Black students should not only be able to see the world around them (they are quite often over-exposed to the lives of others), but they should also see themselves. Black teachers can provide this mirror-establishing an opportunity for students to see themselves in their teachers. This doesn’t mean this cannot happen without black teachers, but it should be strongly considered during the recruitment of teachers.

(3) Diversity is a Strength: The interwoven fabric in many parts of this country demands that everyone, including white students, have a multicultural lens with which to operate. We need our citizens to have cultural sensitivity and at least a proficient level of cultural context to draw from as they navigate life with a diverse population. By having black teachers, we provide all of our students with a microcosm of society, one that is diverse and reflective of our communities. If supported properly, having more black educators can provide a powerful cultural context within schools and communities. Also, we lose the opportunity to tap into a larger pool of talent when black men only make up 2 percent of the teaching profession.

When other students of various backgrounds are taught, nurtured, and mentored by a black male teacher, it is quite likely that some of the racial injustices imposed on black men will be decreased. If a white student who is a future police officer or judge is taught by a highly effective black man, one has to think that it might decrease some of the racial incidents we experience so frequently. For too many white people, perceptions about black men are forged through the negative projections seen in the media. Direct and impactful contact with a black man in the classroom can be a difference maker in a student’s perception.

Recruitment must be seen as the last inning in a World Series game where every player and every decision impacts the ultimate outcome. If we want to prepare our children to be successful players and shapers in the global society, we must make the real commitment to diversify our nation’s teaching workforce.

(4) Purpose, Struggle, and Change: Education is the best lever for change that millions of people can take up and drive right now. Blacks have long been a part of the fight and advocacy for social justice issues. Right now, millions of students of color are trapped in failing schools. We need more blacks to become directly involved in what can be considered, perhaps, the single most important lever: righting the myriad social justice ills we currently face. Health care, overflowing prison populations, low college attainment levels, and poor housing opportunities all plague our communities. A great education is a big part of the weapon against these overwhelming issues. We need blacks to view schools as one of the best battlegrounds for short and long term victories against inequity. We need student-centered revolutionaries in our classrooms.

(5) Ideals for All: To apply the ideals of this nation to all students and communities, we must provide students with a well-rounded education. To do this at optimal levels, we need more teachers, black men in particular, to side with our students of all backgrounds by providing them with a great education-one that is rigorous, well-rounded, and taught by a diverse teaching body. Our students are still facing many forms of injustice-the most ubiquitous injustice of them all is poor education and failing schools. Our students need more advocates, more Freedom Fighters, and more thought partners to push against this wall of injustice.

Some districts play the role of a baseball catcher and will continue to just wait for more black teachers, men in particular, to enter the schoolhouse doors. Districts and principals must possess the mindsets of a relentless scout in search of the “Top Talent” individuals who can expand the diversity within the teaching profession and serve as powerful role models and educators for our students of color.

Our standard approach to recruiting people of diversity into the teaching profession needs to change. Instead of demonstrating contentment with passively “receiving” black educators, the recruitment effort must actively pursue, proactively recruit, and deliberately highlight the amazing opportunity and potential that accompanies diversity.

As black men, we must counter the negative perception about the teaching profession. At times, this negative perception about our noble profession is spread by educators themselves. In Georgia for example, a recent study reported that 67 percent of its teachers were “unlikely or very unlikely to encourage graduates to pursue teaching.”

We should be encouraging our best and brightest to become teachers. Our future generations depend on it. For example, networks like North Star Academies are partnering with Relay GSE to recruit, support, and provide authentic experiences for undergraduates interested in a teaching career. At Mastery Charter Schools, we are incentivizing choosing a career in education to our graduating seniors by promising summer school jobs (working directly with students) for them throughout college.

Recruitment must be seen as the last inning in a World Series game where every player and every decision impacts the ultimate outcome. If we want to prepare our children to be successful players and shapers in the global society, we must make the real commitment to diversify our nation’s teaching workforce. This is a change that can begin immediately. Let’s not wait to act until the bottom of the ninth inning when we can strike a homerun now for all of our students!

Arise, black men, arise. “Accomplish what you will.”

We are asking.

Sharif El-Mekki is the principal of Mastery Charter School–Shoemaker Campus, a neighborhood public charter school in Philadelphia that serves 750 students in grades 7-12. From 2013-2015, he was one of three principal ambassador fellows working on issues of education policy and practice with U.S. Department of Education under Secretary Arne Duncan.

A version of this article was originally published on phillys7thward.org.

Photo header: Flickr/Department of Education