In early 2008, I had lunch at McCormick & Schmick’s with a young, up-and-coming local politico. He had recently returned from a road trip, having packed his then-wife and young kids into the car to make the trek to the steps of the Illinois state capitol to hear Senator Barack Obama declare his candidacy for the presidency of the United States.

I don’t remember precisely what was said during that lunch, but I do remember that this young African American Philly lawyer made a passionate argument for the meaning of Obama. That this wasn’t just another political candidacy, that it represented a new way of doing politics. Obama was in single digits in the polls—Hillary Clinton, the conventional wisdom held, had a lock on her party’s nomination—but across from me sat this living, breathing embodiment of what Obama would go on to identify as the the product of the “audacity of hope.” Williams was effectively predicting the future that day and his passion for change was palpable. I remember getting back to my office and telling colleagues that this Seth Williams guy? He’s somebody to watch.

![]() Well, it’s eight years later, and I can’t help but wonder where that Seth Williams has gone. The change agent who sat across from me has not only turned into the keeper of a tired status quo, this Seth Williams has been a District Attorney with a stunning lack of sound judgment in recent years: Blown prosecutions, stubbornly wrongheaded retrials, an ongoing FBI investigation into his finances (seriously, using campaign money for a Sporting Club membership?) and the expenditures of his nonprofit, The Second Chance Foundation.

Well, it’s eight years later, and I can’t help but wonder where that Seth Williams has gone. The change agent who sat across from me has not only turned into the keeper of a tired status quo, this Seth Williams has been a District Attorney with a stunning lack of sound judgment in recent years: Blown prosecutions, stubbornly wrongheaded retrials, an ongoing FBI investigation into his finances (seriously, using campaign money for a Sporting Club membership?) and the expenditures of his nonprofit, The Second Chance Foundation.

And now comes Williams’ belated disclosure that he accepted a litany of Lifestyle of The Rich and Famous-like gifts—$160,000 between 2010 and 2015!—that has led to speculation that the District Attorney’s office has been for sale. To be clear, I don’t think it was; it seems likely that Williams’ missteps have been due to incompetence and not venality. And let’s concede that, especially early on, Williams enacted some solid reforms, like assigning prosecutors to specific communities and issuing fines instead of jail time for marijuana possession.

But any good Williams has accomplished is far overshadowed by his pattern of suspect judgment. Williams, for example, appears unable to see that accepting perks from, for example, the Eagles when cases involving two of their players were brought before the authorities ought to disqualify one from serving as the city’s top law enforcement officer. Yes, politicians take gifts—especially Philly pols. But the bar should be higher for District Attorneys, because you never know just who might be charged with breaking the law. Every interaction by a prosecutor is rife with the potential for conflict of interest.

Say what you will about Williams’ predecessor, Lynne Abraham—and I’ve often vehemently disagreed with her, particularly when it comes to capital punishment and marijuana laws—but there are few public figures in Philadelphia history with a more pristine reputation for honesty. You won’t find any FBI investigations into her finances, which, when talking about a Philly pol, is cause for commendation. “Even if Lynne Abraham were starving to death, she would not have taken those gifts,” an Assistant District Attorney who served under both Abraham and Williams told me. Williams rose to power in part by challenging Abraham, his one-time mentor, and has now set the credibility of the office back.

![]() Here are just a few of the head-scratchers:

Here are just a few of the head-scratchers:

While candidates for mayor sell their ability to build diverse coalitions and those seeking City Council seats argue that they have unique policy chops, District Attorney races generally come down to one thing: Judgment. Elect me, candidates say, and I’ll make smart choices that keep you safe.

Well, we first started getting an inkling that Williams would be judgment-challenged in 2011, when it came to light that a young female ADA on his staff was having an affair with a Rastafarian drug dealer—the police discovered the relationship while serving a warrant and seeing photos of the two together. When Williams responded with a wrist slap—transferring the ADA to another office, it sent a signal to his staff, another ADA once told me, “that Seth cares more about being a nice guy than a leader.”

Even then, Williams’ ambition seemed all-encompassing. He made national headlines by convicting Monsignor William Lynn for endangering the welfare of a child by protecting a pedophile priest. Williams hailed it as a “historic prosecution.” But rather than focusing on the task at hand, his office focused its efforts on scoring political points by dredging up years of irrelevant history of the Catholic Church. The DA offered evidence of a culture of abuse dating back to 1940, which the Supreme Court found prejudicial, causing it to overturn the conviction. Lynn, after all, had nothing to do with those long-ago cases. Williams’ overreach cost his office a valuable conviction, and cost valuable taxpayer money to pay for a new trial.

Last week, it took a jury to exonerate and release Anthony Wright from prison—three years after DNA evidence effectively cleared him of the murder he’d been coerced into confessing to a quarter century ago. Despite all the evidence, Williams stubbornly went ahead with the doomed retrial, leaving the jurors aghast that the case was even pursued.

Yes, politicians take gifts—especially Philly pols. But the bar should be higher for District Attorneys, because you never know just who might be charged with breaking the law. Every interaction by a prosecutor is rife with the potential for conflict of interest.

Earlier this week, Daily News columnist Stu Bykofsky reminded us of another case in which Williams has stubbornly refused to do the right thing. Bykofsky has argued the case of Marcus Perez for years. He’s doing a life sentence at Graterford after a judge erroneously told him if he pled guilty, he wouldn’t get a life sentence. The judge has copped to a clear case of judicial error, but Williams has consistently stood in the way of righting the wrong.

Why, Seth? Much has been written about the insular world of cop culture, with its “us against them” mentality and its blue wall of silence. Well, the same conditions often pertain to prosecutors, as a ProPublica report made clear a few years ago. In our system, defense attorneys are supposed to advocate on behalf of their client, and prosecutors are supposed to dispassionately administer justice on behalf of the people—including the defendants themselves. But prosecutors are often true believers themselves; they’re human, after all, and given to many of the foibles Williams has exhibited, hubris and blinding ambition among them.

Or how about when Williams hired prosecutor Frank Fina, Kathleen Kane’s arch-nemesis? When, amid all that drama, it came to light that Fina had participated in an offensive statewide email chain—calling it porn is a misnomer, as many of the email videos were as racist and homophobic as can be—Williams’ wrist-slap was not only stubborn, but tone-deaf. Somehow, the enlightened progressive I broke bread with eight years ago had become a de facto defender of the ol’ boys club he was paying lip service to toppling back then.

And now comes the gifts. Boy, oh, boy. The $45,000 roof, the Key West vacations courtesy of a defense lawyer who represents clients facing charges brought by Williams’ office and $6,000 in gifts from a Common Pleas judge who ascended to the bench because Williams had “vouched for him.”

I don’t know about you, but the most I normally get from my closest friends is an obstructed view Phillies seat (now that they suck) and a gift certificate to Hooters. But apparently I don’t run in Williams’ kind of crowd.

City law puts few limits on the acceptance of gifts by public officials, though it requires full and timely disclosure. Williams’ lawyer is seeking to negotiate civil financial penalties with the state Ethics Commission and the Philadelphia Board of Ethics for his lack of disclosure; failing to report gifts can be as high as $1,000 under city rules and are capped at $250 per year under state law.

Kathleen Kane and Williams are not so dissimilar. Because when tests of character come, as they inevitably do in big city politics, relative novices often react from a place of insecurity and ego. Kane and Williams may hate each other, but in their hubris, lack of judgment, and blind ambition, the sad story is that they’re very much alike.

That will probably be the end of the issue of Williams’ gifts. In June, the Supreme Court overturned the conviction of Virginia Governor Robert McDonnell, establishing that there must be a direct quid pro quo tying the acceptance of gifts to official public acts. Despite his odd comments in Philly Mag last month, complaining that he can’t make ends meet on his $175,000 salary, there’s no reason to believe that Williams was cutting quid pro quo deals and selling justice to the highest bidder. No, he was playing the game the way it’s long been played in Philly: With ethical blinders on…which is kind of worse.

I don’t know precisely why Seth Williams lost his way, but I can guess. We’re seeing it an awful lot these days. We see the rapid rise of a new face on the scene—be it Williams or, ironically, his nemesis Kane—and maybe they’re not seasoned enough yet for big league ball. But they do love the celebrityhood. Kane, who had never run for office before, seemed puffed up by the mindless media speculation about her as a presidential contender and was more interested in making headlines—and getting back at those who orchestrated bad ones about her.

Williams, who also had never run for office before his challenge to Abraham in 2005, rolled throughout the city in a black SUV with a team of bodyguards and sure seemed to love his sideline pass to Eagles games. Like Kane, it seems like his life is awash in drama; on Sunday, police charged his girlfriend with slashing two city-owned cars outside his house nine months ago. And, in that Philly Mag interview with David Gambacorta, Williams can’t keep himself from explaining away the FBI probe as the work of Kane’s dirty tricks—as if she’s proven herself to be a master Machiavellian player who would have the power to orchestrate a federal investigation.

Come to think of it, Kane and Williams are not so dissimilar. Because when tests of character come, as they inevitably do in big city politics, relative novices often react from a place of insecurity and ego. Kane and Williams may hate each other, but in their hubris, lack of judgment, and blind ambition, the sad story is that they’re very much alike.

Yes, no doubt, both have had detractors bent on bringing them down. But both have also embraced their own victimhood and specialized in ill-advised decision-making. For example, let’s forget the Ethics Board and the laws surrounding disclosure. If you’re the District Attorney, never knowing just whose case might come before your office, don’t you know—like Lynne Abraham knew—that the right thing is not to compromise the perception of your office by taking anything from anyone? (Remember, Williams punted on investigating John Dougherty earlier this year, kicking it to the state, because he’d accepted campaign donations from the labor leader). Do we need ethics laws and ethics training for public officials to know this? Seems to me, the Seth Williams saga—like the Kane soap opera—is proof that all the ethics laws in the land won’t create ethical public servants.

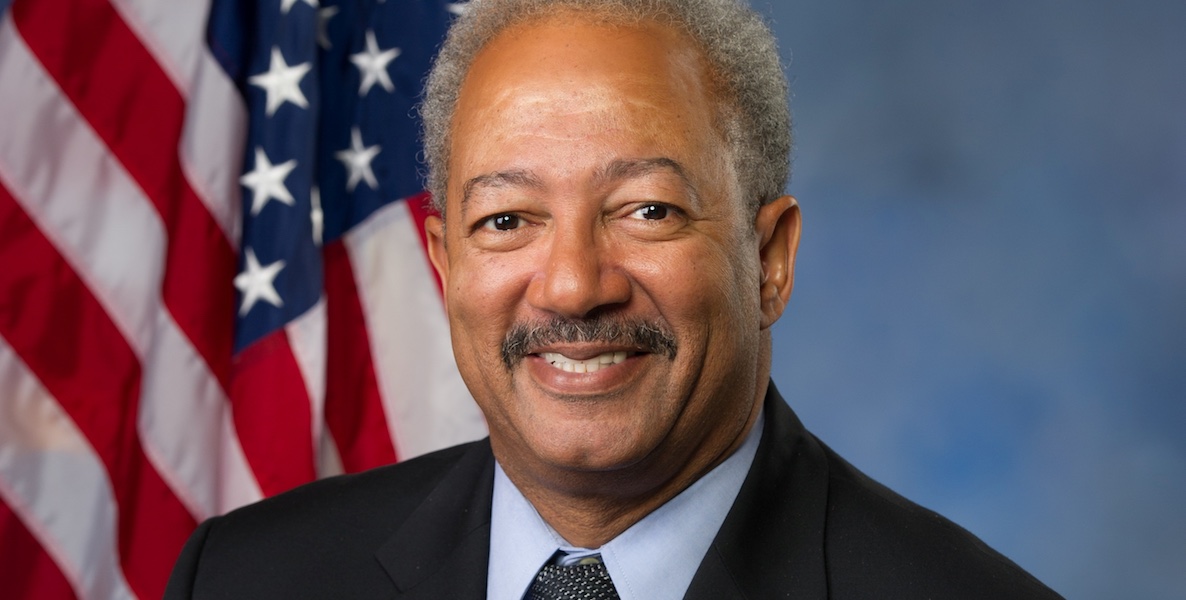

Header photo by Flickr/Philadelphia City Council