Nine neon signs hum and glow in the front windows of Temple Contemporary. They tell you if the gallery is open or closed, if there’s a lecture that day, or if it’s sun or rain outside. You walk in, but can’t find the title of the exhibition, nor the curatorial statement. Instead, you’re invited to take a sip of water that was distilled from Coca-Cola. Or observe bees in an artist-designed beehive. Or take a seat, from any of the 75 mismatched chairs off the walls, each one representing a cultural organization in Philadelphia. Let’s assume you’re confused, so you take a closer look at a gallery label. But even the label is unconventional, hand-drawn with ink recycled from the soot produced by the glass department down the hall.

These signifiers let you know not to expect a typical gallery experience. To understand what’s going on at Temple Contemporary, you have to dive into the unique vision of its director, Rob Blackson.

Blackson, who moved to Philadelphia five years ago to become the director of Temple Contemporary, looked at the cultural landscape here to see a city full of galleries and museums operating in the typical fashion: An artist or group of artists, assembled by a curator, explores an issue within the white walls of a gallery, to an audience enticed with free wine and cheese. “We needed to find a niche,” remembers Blackson. “We didn’t want to add more broth to the soup.”

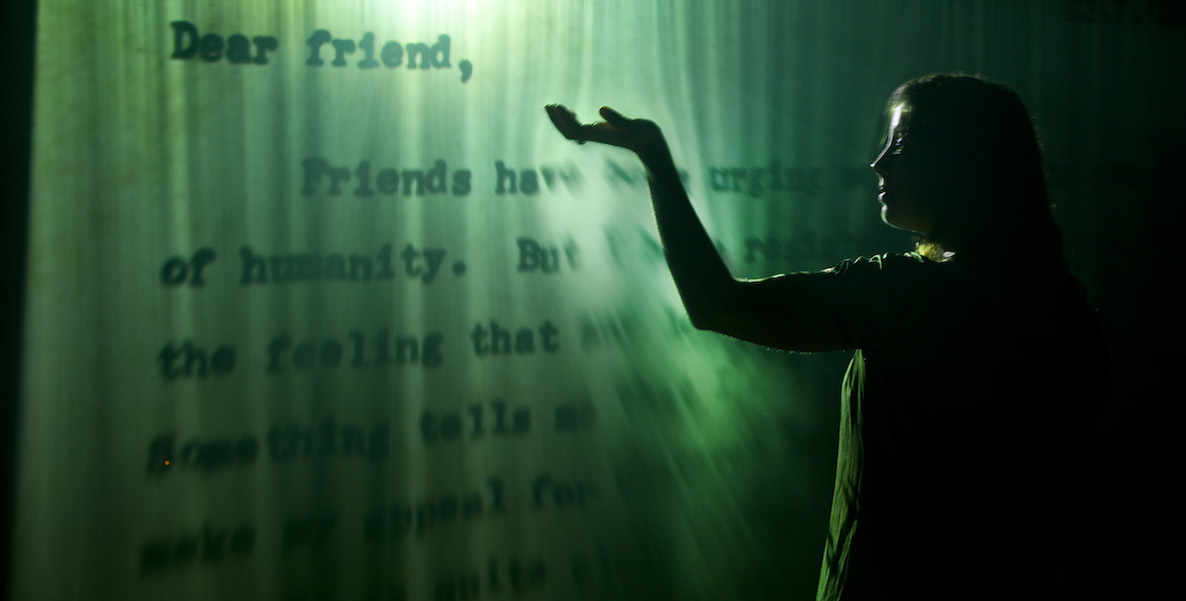

So Blackson decided to flip the script, taking his cues from the city around Temple, rather than telling the community what he wanted them to see. For example, take the 2014 reForm project. In 2013, city authorities announced that two-dozen Philadelphia schools were being shuttered. In response, Temple’s Youth Advisory Council, a panel of 10 high school students in paid positions to advise the gallery, wondered, “If the walls of a closed public school could speak, what would they say?”

With this assignment, Blackson found a partner in fellow Temple professor and artist Pepon Osorio, who collaborated with former Fairhill students to gather objects and stories in the wake of this school’s closing. The resulting reForm exhibition set off to answer the Youth Advisory Council’s provocative question— and this line of inquiry into the public school system has driven Temple Contemporary’s programming now for four years.

The program doesn’t just bring in participants, but asks its community members to become leaders. “Temple Contemporary creatively reimagines the social function of art, so it needed to function differently,” says Blackson.

The Youth Advisory Council is only one such group to the gallery. Blackson also created a 30-member advisory council—made of 10 Temple students, 10 Temple faculty, and 10 civic/cultural leaders—to advise Temple Contemporary’s programs. This group was asked to bring their curiosity, and offered a real chance to set the program’s agenda. The program doesn’t just bring in participants, but asks its community members to become leaders. “Temple Contemporary creatively reimagines the social function of art, so it needed to function differently,” says Blackson. “[The Advisory Council] is a wonderful, wide-ranging group that ensures our efforts are not unilaterally determined, but responding to a communal effort embodying the breadth of contemporary life in Philadelphia.”

Temple is a sort of homecoming for Blackson, who was born in Altoona, before studying at the Rhode Island School of Design, Edinburgh College of Art, and Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College. He began to develop his unique vision as the curator of public programs at Nottingham Contemporary in the United Kingdom. Nottingham has one of the largest art spaces in the U.K., hosting the standard art programs: big exhibitions, lectures, film study. Blackson’s job was to connect the gallery exhibitions to local civic and education spaces, “trying to find the through lines with the public university.”

But at Nottingham, he grew to lament the fact that his community partnerships only ever lasted as long as the exhibitions themselves. And more, that it was exclusively the curatorial staff of Nottingham—Blackson and others—who drove the issues being explored. This was typical art world thinking, with curators and museum directors controlling cultural exploration.

It was Blackson’s time at Edinburgh College that showed him there could be a different way. As a young sculpture student he expected he would follow the standard career path: making work in his studio, waiting for a powerful curator to discover the work, and finally enjoying his turn as a legitimate artist. But the older students at Edinburgh refused to follow this narrative. Blackson recalls being amazed by these students organizing their own shows in off-the-beaten path venues around town—much like the DIY-gallery-movement that drives so much of Philadelphia’s art scene. Seeing this energy changed Blackson’s thinking about power in the art world.

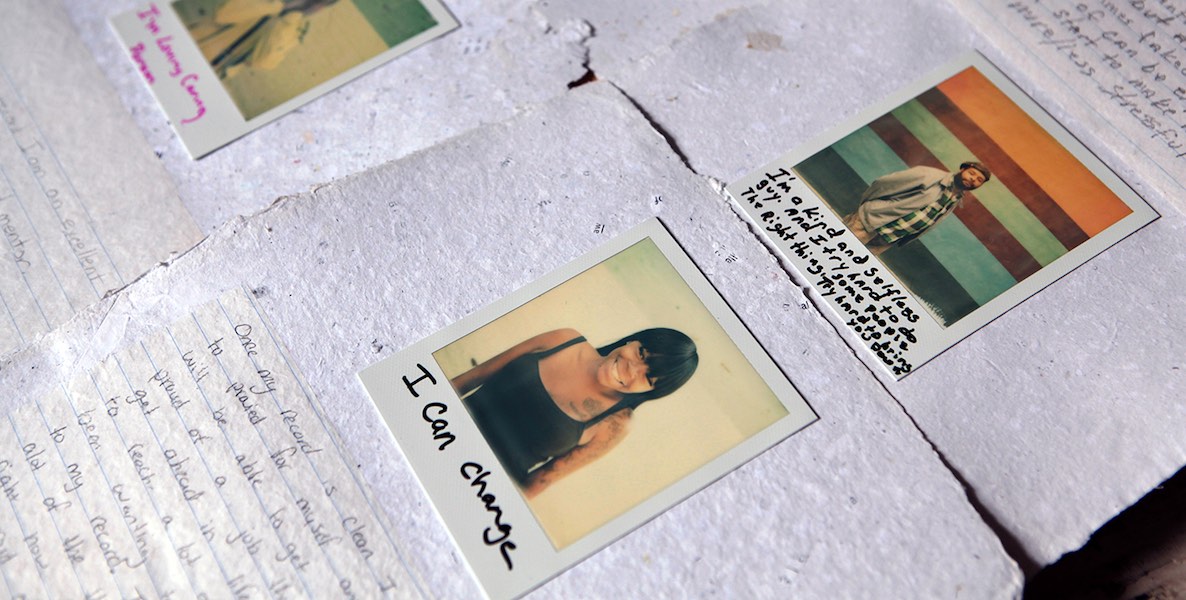

At Temple Contemporary, Blackson has developed that notion into a more vibrant system that harnesses the energy of an engaged community. This thinking prompted one of his early projects, Funeral for a Home. As he tells the story, it started during a meeting of the advisory council, when a member stood and said, “I was looking for parking, and I realized that I’m surrounded by blight. There are more houses than people to fill them!” Another person asked, “What do these houses deserve before we pull them down?”

With local artists Billy and Steven Dufala and Jacob Hellman, Temple Contemporary responded: a funeral service. For the resulting Funeral for a Home, the team searched for a house set for demolition in the next year, that could represent all of Philadelphia’s housing stock. They settled on 3711 Melon Street in Mantua.

On the morning of May 31, 2014, over 500 neighborhood “mourners” gathered to celebrate the life of 3711 Melon Street, which the artists dressed up in its finest funeral wreath. Lifted by the gospel singing of the nearby Mt. Olive Baptist Church choir, the day also included remembrances from the homeowner’s relatives and local neighborhood leaders, proclaiming a brighter future. One speaker opined, “If you can have a funeral for a house, there’s a resurrection. And the resurrection should be the neighborhood.” Later, Pastor Harry Moore, Sr. of Mt. Olive, delivered a fiery eulogy, reminding the audience , “We are here to remember the past. We are here to reflect on the present. We are here to look towards the future.” After the service, the crowd looked on as an excavator began to tear down the bricks, and place the debris in a dumpster-turned-coffin, designed by Billy & Steven Dufala.

“This project gives us a moment to reflect on these houses and also reflect on the lives that have been shared in those homes,” said Blackson. “[Poet Thomas] Lynch (who is also a funeral director) made a comment in his book that ‘mourning is romance in reverse’ and I feel that this is true of Funeral for a Home.”

This type of project is possible only with a director “fed up” with an insular art community.

Blackson has built a program at Temple Contemporary that is a departure from most university galleries. Typically, these museums hold exhibitions that attract recognizable artists to raise the profile of the university, attract visitors to the school, and expose the student body to professional art practice—all under the direction of a curator, well versed in an art world jargon that’s incomprehensible to most of the public. Blackson doesn’t refuse these roles, but sees in Temple University’s mission a dynamic new way to achieve them.

“Temple is the city’s university,” he says. “It’s estimated that one-third of Philadelphians have taken a class at Temple.” This breadth gives Temple Contemporary a unique platform to use art to examine the civic issues that face Philadelphia. The questions that drive the gallery are brought into Tyler School of Art classes, and by looking at the whole city as its campus, Blackson empowers students to become an educated citizenry. “A lot of universities put their walls up—community is just another word. Temple Contemporary has tried to lead a more nuanced conversation.”

“Temple is the city’s university,” he says. This breadth gives Temple Contemporary a unique platform to use art to examine the civic issues that face Philadelphia

With over 35 events each season, Temple welcomed 17,000 visitors last year, up from 2,250 in the year before Blackson’s arrival. Those types of numbers can justify the university’s funding for this unique program, with additional support for the largest projects from individual foundations.

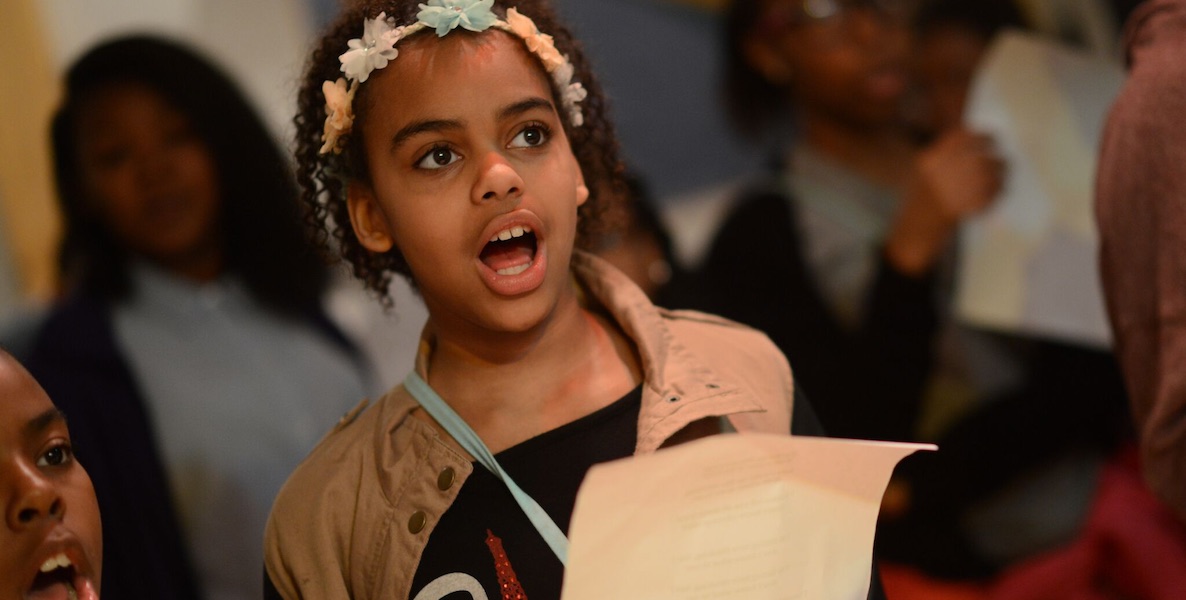

Temple Contemporary’s most recent project continues its inquiry into the state of public schools, after a prompt from the Advisory Council noting that music education funding had fallen from $1.7 million to $50,000 in the last 10 years. For Symphony for a Broken Orchestra, Blackson called on music education teachers across the city to drop off their broken musical instruments—1,500 in all, with no budget for repair. To Blackson, that meant 1,500 kids who would not receive an instrument.

He wondered, “What is the social function of an orchestra? How can we think of broken instruments as more than just a problem, but an opportunity for creative reuse? Is there a way to imagine the problem as its own solution?”

These “uniquely-wounded” instruments are currently hanging on the pristine walls of Temple Contemporary. This fall, “Found Sound Nation” will document and record the sounds of these broken instruments, and composer David Lang will create a score using the sounds only they can make. The piece will be performed in October 2017, with musicians from the Curtis Institute of Music and the Boyer College of Music and Dance. But the project doesn’t stop there. In the spring of 2018, instrument repair specialists will take select instruments back to their shops for repair. The plan is to return the fixed instruments back to the schools by fall 2018.

Displaying broken objects, placing projects far from the white walls of the gallery—these capture the spirit of Blackson’s radical gallery program. One that re-imagines the university not just as a safe space for like minds, but as a training ground that, as Blackson describes, “empowers an educated citizenry that reimagines the problems of a city as its own solution.”