History 101: A crisis can make a system stronger, or lead to its demise.

![]() Take post-Depression America versus that same era in Germany. While FDR focused on progressive ideals to restore jobs and save farms and businesses, Hitler preyed on economic uncertainty to rise to power.

Take post-Depression America versus that same era in Germany. While FDR focused on progressive ideals to restore jobs and save farms and businesses, Hitler preyed on economic uncertainty to rise to power.

Or look to New York, which emerged from 9/11 with, for example, stronger counter-terrorism policy and practices.

And the same principle applies to schools. In New Orleans post-Katrina, the best charter schools in the country flocked to Louisiana to help re-start the school system from scratch—and students started succeeding in ways not seen before.

So what will the global pandemic mean for Philly schools?

The School District of Philadelphia has spent the last several weeks responding to the urgent, immediate needs of its 130,000 students—food, laptops, hotspots. But the pandemic has also shined a light on the issues that have always existed here—poverty, the digital divide, crime, homelessness…and so on.

And it is simply unconscionable to ignore these challenges any longer.

“Crises have the tendency to sharpen the gaze,” says Temple Professor of Educational Psychology, Dr. Avi Kaplan. “They make salient particular aspects of the world that previously were either masked or ignored. They make goals clear and then priorities between goals clearer. And they also demonstrate the visibility of decisions and actions that at other times would have been thought of as impossible or unthinkable.”

“If we’re going to make education the foundation of recovery from this really great crisis, then we have to modernize, and see that this is really a societal necessity for equity, and for overall societal well-being,” says Cahill.

“Whether this crisis will result with desirable change depends on the decision-makers and what priorities they highlight,” Kaplan says.

We’ve already seen some heartening first steps, as when the School District, City, and philanthropists came together to provide Chromebooks for our students, demonstrating that progress—while challenging—is possible.

To continue to innovate and improve, we asked several experts what questions we need to address in the post-Covid era:

How do we make digital access in 2020 like electricity in 1930?

When FDR created the Tennessee Valley Authority, part of its mandate was to bring electricity to every pocket of the United States. Michele Cahill, senior advisor at XQ Institute, the nonprofit that was launched in 2015 to help educators and communities redesign the high school experience, argues that we need to take the same approach to WiFi if we want to even think about leveling the academic playing field.

“Big providers have to come to the table with government and communities to figure out how to solve this,” Cahill says. “If we’re going to make education the foundation of recovery from this really great crisis, then we have to modernize, and see that this is not something that is individually up to parents, but that this is really a societal necessity for equity, and for overall societal well-being.”

Cahill and her team say that while these kinds of collaborations aren’t happening broadly enough yet, we can look to the realm of food insecurity as an example of private/public partnerships that work to address a huge urban problem.

And throughout history, she says, whether it was programs like the Morrill Land-Grant Act to broaden access to higher education or the expansion of the TVA to broaden access to electricity, our nation has shown its capacity and sheer will to come together for the greater good.

![]() “Covid-19 has made inequality worse and there’s certainly no silver lining [in that], but there are choices and opportunities for mobilizing and showing how this country can rally [and] create solidarity like Americans have done in the past,” she says.

“Covid-19 has made inequality worse and there’s certainly no silver lining [in that], but there are choices and opportunities for mobilizing and showing how this country can rally [and] create solidarity like Americans have done in the past,” she says.

Meanwhile, the School District of Philadelphia has taken a step towards this: In a recent virtual press conference, Superintendent William Hite said the district has acquired 2,500 hotspots, at a cost of about $185 each—annually.

“It’s not a problem that the District is going to be able to solve given our financial forecasts,” Hite said. “And so we’ll have to work with the city and others, and I’m working with other superintendents across the country to really look at this whole internet access [issue] as a critical infrastructure issue. People should have access to information, particularly if we have to use this to educate children, just as they have access to meals and nutrition.”

How do we rethink the structure—and drudgery—of the school day?

We know that little ones have a hard time sitting still, that tweens need peer contact, that teens need more sleep, and that everyone benefits from variety. But for years, the arguments against fixes like more recess for kids or delayed school start times for high schoolers have largely come back to the interdependence of resources like childcare, buses, playing fields, inter-school athletics, and after-school jobs.

Now, when all of those have been disrupted, might be the best time to start from square one. “This is an opportunity not just because our system has been destructed, but all systems have been destructed,” Kaplan says.

There’s a real burden in a schedule that requires students to move from class to class every 45 minutes throughout the day without adequate recess and with numerous assignments in each class. “It hinders meaningful engagement,” Kaplan says.

It’s more important to structure students’ days with breaks, to diversify their thinking, to have some social activities and then some individual activities, to do things that are physically active and then some that are more restful, some arts, some humor, some academics. Kaplan says we should take the insight we’re getting from the structure of our at-home school days to ask, “What should school look like to reduce drudgery, reduce monotony, reduce load, and allow an opportunity for meaningful engagement and learning?”

In the Philly area, there are several independent-progressive schools that already practice diverse daily schedules, and they can be models. The Philly Free School allows students to design their schedules completely; there are semi-structured schedules at The Miquon School and the Project Learn School; and there are programs that weave together diverse activities based on theories of childhood development, like Waldorf and Montessori. The District could think about adapting some of these approaches, to be pioneers in incorporating them into public school to enhance students’ learning, and agency, over their own education.

Why not re-think assessments?

Another example of interdependence that will be interrupted in the short-term, and could pave the way for positive change: assessments. The School District is dependent on the university system and all its admission rigamarole; but right now, the admission procedures at universities have been disrupted, and a lot of universities are dropping standardized testing as requirements for admission.

“We have this opportunity to raise up the status of teaching now that teachers are being valued more and parents are getting a really close-up view of what goes into teaching and learning,” Cahill says. “The expectations that teachers will teach remotely on a dime shows how important investment in professional development and training is.”

“This has already been going on with the rise of test-optional admission and people realizing that the SAT, ACT, and GRE reflect students’ resources more than anything else, and that using them for admission is actually undermining diversity and access for students from currently underrepresented groups,” Kaplan says. “So this could be a great natural experiment, to follow these kids who will be admitted on different criteria to see their success, their completion of degrees.”

Pamela Cantor, MD, is a psychiatrist and the founder and senior science advisor at Turnaround For Children, an organization that helps educators address the impact of stress and trauma on children’s learning and development. She argues that now is the time to shift our focus away from grade-based assessments all together.

“Most of us [in the educational realm] have thought for a long time that grades are a very artificial and arbitrary marker of what kids know,” she says.

Competency-based assessments, like those conducted at C.B. Community Schools, and assessments that talk about the progress made from week to week, will be much more valuable during this time. “[Eliminating grades] is one thing policy makers can do now to take a very unnecessary and unhelpful pressure off of kids and families,” she says.

In Finland, where students are typically not even assigned homework, assessments are more about giving teachers the necessary feedback they need to coach students, than they are a way to judge youth. And that’s not a bunch of frou-frou ideology: The high school graduation rate in Finland is 99 percent. In Philly, with its testing and homework aplenty, the graduation rate hovers at 69 percent.

Kids will catch up, Cantor adds—but pounding them with academics at a time when the experience of stress is a daily part of the lives of families and kids is not going to be productive, and is only going to add stress to an already difficult situation.

How do we better support—and attract—teachers?

With the much-deserved outpouring of gratitude for teachers right now, the profession is finally getting the respect it deserves. So how do we channel this reckoning, and make teaching, as a profession, more desirable for more people? Eliminating some of that drudgery could help—not only on a day-to-day basis, but insofar as freeing up more time for teacher development and training.

“We have this opportunity to raise up the status of teaching now that teachers are being valued more and parents are getting a really close-up view of what goes into teaching and learning,” Cahill says. “The expectations that teachers will teach remotely on a dime shows how important investment in professional development and training is.”

Lesson study, she says, has been proven to be a really powerful professional learning and teacher improvement tool, as seen in Japan, where the practice began. Similar in spirit to the revered business practice kaizen, the notion of constantly iterating and improving, lesson study as it began in Japan focuses on teachers collaborating to develop, analyze, and improve both the content and presentation of material.

“That notion of having more design and planning time while you figure out how to give assignments that can be supported through small groups and can be done in an in-person or in a technology-based way—teachers and students could really build on that,” she says.

Paying teachers more would also naturally attract, and retain, more of them. In a compelling article in The Atlantic last September, University of California-Berkeley economist Sylvia Allegretto and her colleague Lawrence Mishel found that whereas in 1979, teachers earned 7.3 percent less than other professionals, by 2018 they earned 21.4 percent less. Acknowledging that increased salaries won’t solve every educational woe, they maintained that “school districts and lawmakers alike must recognize that would-be teachers have other, better-paying job options—and that drawing college graduates into education will require paying them more.”

There are ways to do it: As recently as January, California governor Gavin Newsom proposed giving teachers in high-needs high schools $20,000 stipends, and last year Senator Kamala Harris proposed $13,500 pay increases to teachers, which could come from tax reform, like increasing the estate tax.

As Allegretto and Mishel concluded in their research: “Will, not wealth, is what’s lacking.

How do we help students with differentiated needs?

If we are looking at at least another 18 months of on-again-off-again digital learning and a greater reliance on digital tools beyond that, we desperately need to think about better serving students with complex needs and their families. For a student who has trouble with executive function or focus, for example, expecting them to follow an at-home to-do list or instructions with multiple steps is simply unrealistic.

This can be done, Cahill says, if we build on what we’ve already experienced ![]() with the supportive use of technologies to personalize catch-up or acceleration and offer extra support. “What we have to do is build on everything we know to figure out ways of personalizing the language using both teacher tutoring and online tutoring, so that students are not held back in some macro way,” she says.

with the supportive use of technologies to personalize catch-up or acceleration and offer extra support. “What we have to do is build on everything we know to figure out ways of personalizing the language using both teacher tutoring and online tutoring, so that students are not held back in some macro way,” she says.

Jenny Bogoni, executive director of Read By 4th, the Philly coalition that focuses on ensuring all children can read by grade four, points out that teachers in our country are trained to serve the 80 percent or so of students who can more or less make it through school without any special support. “And then we have reading specialists and learning resource people and all these other folks that are there to push in and add support to the children who need it,” she says.

But in our current at-home, digital-focused system, it’s very hard to connect to those learning resources, which really are personal relationships, not electronic. “How that gets translated and what our system is for that, is just one sliver of the greater issue of the many ways we use schools to deliver additional supports,” Bogoni says.

Just as, when buildings close, we find ways to deliver food, we need to find ways to deliver all extra supports, and not let them disappear. According to Hite, the District is in regular—weekly, twice-weekly—contact with other city agencies, from the Office of Children and Families to the Department of Human Services, and others; their continued collaboration could pave the way for students with disabilities and learning differences to get the support they need. In the meantime, they have these online resources for families of students with special needs.

How do we involve families (realistically)?

“Never in the modern history of our education system has the importance of family engagement been more apparent,” says Alejandro Gibes de Gac, the founder and CEO of Springboard Collaborative, the Philly-based national nonprofit which focuses on closing the literacy gap by bridging the relationship between home and school.

“All too often, we approach parents as liabilities rather than as assets,” he says. As a culture, he goes on, we look at our low-income parents and don’t see the very same love, commitment and potential that we so easily recognize in a higher-income parent. “We’ve underinvested in them. And now that school isn’t an option on the table, we’ve gotta take a hard look at the ways in which we need to proactively begin supporting families to play the roles that they and only they can play.”

“If there’s a silver lining in any of this,” Gibes de Gac says, “my hope is that we can fundamentally reshape the relationship and the dynamic between school systems and low-income parents.”

Springboard, which at one time had as its president and CFO/COO Congresswoman Chrissy Houlahan, has seen dramatic success in the 14 school districts around the country with which it collaborates: 91 percent of parents attend weekly workshops to learn how to teach their child reading at home, and in most cases, these are the parents of the lowest performing readers within the lowest performing schools within districts that are serving under-resourced communities.

“If there’s a silver lining in any of this,” Gibes de Gac says, “my hope is that we can fundamentally reshape the relationship and the dynamic between school systems and low-income parents.”

Springboard’s methods, which are rooted in goal-setting as a way to measure outcomes and produce meaningful data, take into account the limited resources and even more limited time families may have, and have proven that outcomes can improve by spending just 15 minutes every day, for five weeks, working on goals.

Cantor’s work has found the same benefits. “In every single story of a person who has surmounted adversity, the one ingredient that is common in those stories isn’t money or privilege—it’s a person, a relationship,” she says. “And the one thing any parent can provide that is more powerful than anything else in the world right now is giving your child courage and belief in herself. Nothing is more important than that today.”

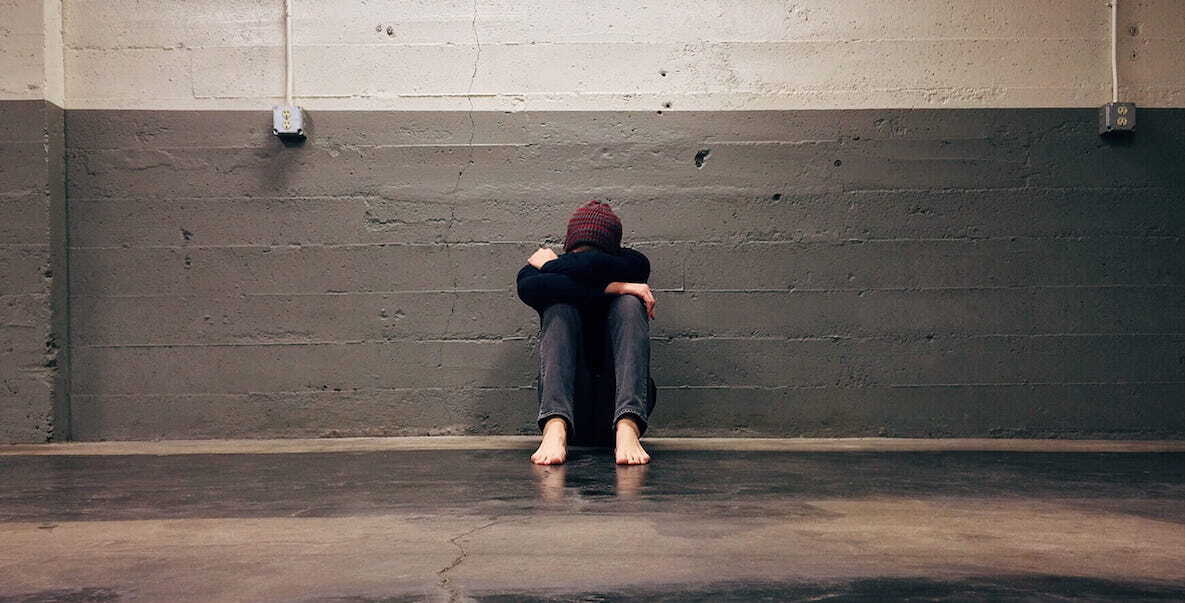

How do we support student mental health?

Trauma is woven into the fabric of our students’ lives—there’s no way to grow up around poverty, crime, homelessness, and the opioid epidemic without it taking a toll. Add to that the weight of the pandemic and the problems it will fuel—unemployment, lack of adequate healthcare, loss, and grief—and our students are being asked to bear too great a burden.

Our youth mental health crisis can no longer be put on the sidelines: Heading into any new school environment, we must establish the best trauma-informed resources for our students, and their teachers.

“We need to think about what reentry to school is going to look like in terms of how to be aware of the social emotional needs of everyone: students, school leaders, and parents,” says Valerie Klein, assistant clinical professor and program director for teacher education programs at Drexel.

Cantor says we must adopt a three-tiered approach to mental health, and provide training for all school personnel to make it effective. Tier one addresses the climate of the school, the activities that govern the way the entire school environment feels, like discipline practices, and having those be pro-social. Tier two refers to the supports that are provided in a classroom by a teacher to a student, to strengthen that connection—journaling, book discussions, and talks. And the third tier is accurately recognizing when a child needs a mental health service.

“We must enlist literally every adult in the school to be able to play a support role for children,” she says. “We need an entire school building of adults who understand something about the science of stress and the brain, the impact it has on the learning centers of the brain and emotions, and how to distinguish the earlier signs of issues that warrant an intervention.”

Professional development could fill this need. Cantor’s team at Turnaround For Children says that the ideal way to start is by working with both the District and schools at the same time. In their district partnerships, Turnaround provides professional development throughout the year on the science of learning and development and the impacts of stress and trauma. It’s done with cohorts of principals and their leadership teams, so that they develop trusting relationships, learn together, and develop implementation strategies together.

Then they provide the leadership teams with toolkits filled with specific knowledge, strategies, and practices so that they can build the climate, conditions, relationships and tiered support systems with their faculty and staff in their individual schools.

“The pressure of a crisis, as hard as it is, can drive innovation,” Cahill says. “But only if the choices are made to invest in it.”

There has been some work here on this already: On May 7, Dr. Jayme Banks, director of Trauma-Informed School Practices for School District of Philadelphia, and Meghan Szafran, director of School and Community Services, Uplift Center for Grieving Children, announced the launch of the Philly Hope Line, a hotline staffed by masters-level clinicians to address students’ and families growing mental health needs. Its creation is being funded by an anonymous donor.

“This Philly Hope Line will be able to provide the emotional support for kids and families, who’ll be able to reach out if they’re feeling lonely, anxious; if they’re just not sure where to turn, we can connect them with other resources as well,” Szafran says. In addition to calling, there are also text and video options.

Who’s gonna pay for this?

Everyone wants better schools. But transforming them will take money. At the end of April, Superintendent Hite joined 61 superintendents from the nation’s largest cities in requesting an additional $175 billion from Congress to support public schools. But whether that comes through or not, more must be done. We need the private sector to come to the table. We need to cut the red tape that stalls progress and remove the walls that keep out innovation; now is the time to re-think bureaucracy and focus on the needs in the classroom.

“We know there are funding inequities, we know that the funding formula in Pennsylvania is not doing what it needs to do to create equal schooling for kids. And so I think it is demonstrating that the private sector could have an impact, and that’s another area we really need to push to rethink so that in times of crisis, all Philadelphia and PA kids are served well,” says Klein.

Cahill sums up all of it—the questions of funding and families, mental health and more—neatly: “The pressure of a crisis, as hard as it is, can drive innovation. But only if the choices are made to invest in it.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story misstated Ms. Cahill’s title; she is Senior Advisor at XQ.

Photo courtesy woodleywonderworks Flickr