Since the 150-year old Philadelphia Energy Solutions refinery exploded and finally shut itself down in a spectacular mix of divine intervention and federal law-breaking, the public story around that site in Southwest Philadelphia has focused mostly on 1,000 jobs lost.

Yet, there’s been little emphasis placed on the future of the surrounding and mostly Black communities within toxic stone’s throw of the refinery—or, the more than 1,000 residents who have, for generations, struggled with constant illness as a result. The extent of that damage has not been adequately assessed in the public space. Through the geolocation of cancer mortality rates in that area, we can tell people have died in the plant’s pollution zone, and long before the explosion. We know how bad, we just haven’t properly or thoroughly assessed how bad since neither the City nor state nor any major institution in Philly has yet to commission an authoritative study.

Granted: the last thing a perpetually-depressed city like Philly needs is another hit on its economy, especially when—at least on paper—it’s been managing a steady (and bumpy) recovery from the Great Recession. As a result, the Philadelphia Way is to prioritize jobs and bills over health—even when those two topics are highly intersected and influence the state of the other. Philadelphians know healthcare is extremely important, but we also know that it doesn’t make much sense to end up homeless or hungry even if you’re visibly in good health. Not having a livelihood makes the health part that much harder. It’s a difficult balancing act a poor city makes.

But, beware the economic calamity narrative, Philadelphia, when unpacking the fate of the Philadelphia Energy Solutions refinery.

34 percent of the respondents “living near the refinery had asthma at some point in their life, compared to the national average of 7.7 percent.” More than 52 percent of respondents had “one or more of the following health conditions: asthma, heart disease, cancer, or another respiratory condition.”

Pollution of the kind from the PES refinery causes major devastation to community health that, ultimately, ends up as an endless economic crisis, too. That’s what city, state and federal officials have not yet addressed or examined. The last attempt to do that in any meaningful way was the PhillyThrive #WeDecide Survey Report in 2017: In that, 34 percent of the respondents “living near the refinery had asthma at some point in their life, compared to the national average of 7.7 percent.” More than 52 percent of respondents had “one or more of the following health conditions: asthma, heart disease, cancer, or another respiratory condition.” And when we look at citywide cancer mortality rates, we find clusters of the highest concentrations around the refinery.

That is not just bad for health; it’s also expensive. According to Centers for Disease Control, asthma alone costs individuals more than $3,200 each per year, totaling about $80 billion nationally. Children with asthma miss more school than their peers, putting them behind; adults miss more work. And, unsurprisingly, it’s low-income families who are hardest hit. It’s about the same for cancer: the total national cost of “direct medical costs” for that were more than $80 billion in 2015 according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

“Federal laws really protect refineries from revealing public health impact,” explained Councilwoman-at-Large Helen Gym during a segment on WURD’s Reality Check. “Philly has not prioritized environmental racism, and the impact on vulnerable communities, children, people of color.”

Indeed, the overriding message in the City of Brotherly Love is that it cares more about the future of a refinery than it does about the future of residents. So, for example, if something that massive blows up, don’t worry about the health of residents in surrounding neighborhoods; worry about the economic impact. City, state and federal regulators haven’t even bothered to disclose the fact that the refinery explosion could have turned much worse: with over 400,000 pounds of hydrofluoric acid stored on that site, there could have been an airborne disaster injuring and/or killing “hundreds of thousands” of residents, as Daniel Horowitz, an organic chemist who served as managing director of the U.S. Chemical Safety Board, noted recently in The New York Times.

The overriding message in the City of Brotherly Love is that it cares more about the future of a refinery than it does about the future of residents.

That’s troubling, because it hints at a sinister effort on the part of regional leaders to keep that plant open at all costs, erroneously conflating it with the Hahnemann Hospital debacle. Local media, for the most part, is complicit: headlines have jumped on that “save-the-workers” bandwagon, with coverage squarely focused on how the combination of both PES refinery and Hahnemann Hospital will hemorrhage roughly 4,000 jobs in an economic apocalypse. Even after the explosion, even if the refinery continued violating the Clean Air Act, even if it owed $4 billion in unpaid taxes and even if it’s always been the city’s greatest air polluter and a large existential threat to residential health.

Fortunately (more like luckily) no one was killed on site from the June 21st explosion. But it was telling how nearby residents received no warning of what had happened beyond the boom sounds and trembling of earth. There were no citywide emergency sirens activated, despite the Kong-like size of the burst, and no real indication that city or state health officials embarked on any major effort to check on neighboring residents who’ve complained for years about how much Philly’s top air polluter had damaged their health.

Share your thoughtsDo Something

More telling is a weird and downright obscene level of shrug from most city leaders on the public health dimensions of not only the explosion, but from the plant itself. It’s a barrel of bees City Hall, Harrisburg and the Commonwealth’s Congressional and Senate delegation don’t want to pry open. And, perhaps, that’s understandable: the fear of just how bad that refinery-instigated health crisis might be throughout South and Southwest Philly is deep. Poking around may unleash a torrent of horrific stories, and potential lawsuits. Determining liability could be treacherous and exhausting, with the city absorbing blame for regulatory neglect as much as the bankrupt refinery is held responsible for polluting in the first place.

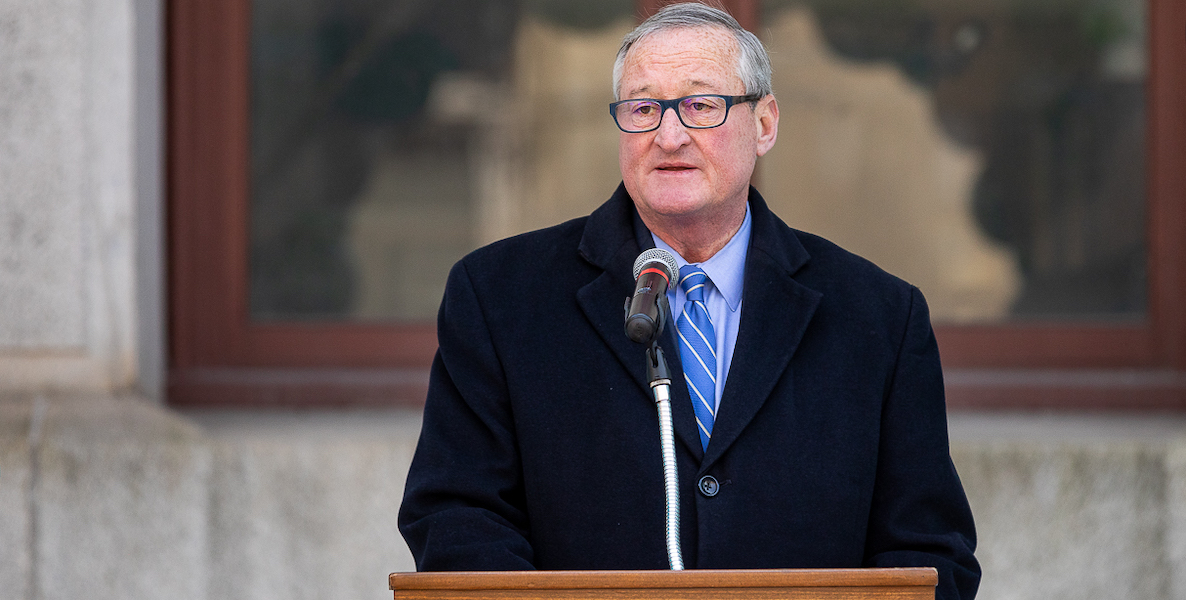

As a result, few have engaged in any meticulous effort to investigate or even ask how much that refinery has devastated resident health, more specifically the residents who live next door to it. You see this in the responses from Philadelphia leaders—who all appeared to quietly coordinate and settle on simultaneous press releases offering boilerplate language on the need to protect the jobs. Mayor Jim Kenney issued a battery of statements offering updates since the explosion, doing what a mayor should do during an event like that. But, even as he pressed to “… immediately convene a group of City and quasi-governmental organizations to discuss the economic and employment impacts” as of a June 26th statement, he steers noticeably clear of the public health question and gives neighboring residents nothing outside of obligatory “air monitoring.”

Mayor Jim Kenney issued a battery of statements offering updates since the explosion, doing what a mayor should do during an event like that. But, even he steers noticeably clear of the public health question and gives neighboring residents nothing outside of obligatory “air monitoring.”

Even the city’s own health Commissioner, who’s quick to jump on WURD’s Reality Check for a conversation on people’s smoking habits—which, granted, is also another epidemic in Philly—is avoiding the program for a conversation on the broader and much more dangerous public health impact of the PES refinery. Which means the city is more likely to pounce on Philly’s mostly Black residents about personal health, dietary and wellness choices than express public outrage at large industrial polluters who contribute to the daily deterioration of that same health.

Others, in and beyond City Hall, are also strangely avoiding the illness question. The state legislator who represents the district where the refinery is located, Rep. Maria Donnatucci is focused exclusively on the jobs, avoiding the health discussion altogether. “We’ve been at this similar crossroad before when there was discussion about closing the refinery in 2012,” said Donnatucci in a statement (on, yes, June 26th). “I worked with many parties to prevent its shutdown and save jobs then, and I’m hopeful we will be just as successful this time around. I have always sought to balance the economic and environmental concerns surrounding this refinery, and I will continue to do so.”

Articles by Charles D. EllisonRead More

Newly-elected Congresswoman Mary Gay Scanlon, who represents that same district where the refinery is, struck a similar tone in another same-day statement. “We’ve been in touch with United Steelworkers and local labor leaders, and are planning to convene a community listening session in the coming days,” said Scanlon, reading from the same crisis communications playbook plan like everyone else. “We will be sure to notify workers, local elected officials, and the community of this event once details are finalized.” But, no word on whether she was in touch with local residents and advocates about the years they’ve spent desperately trying to get someone to pay attention to their health needs after years of toxic exposure.

That was the same from Senator Bob Casey, albeit shorter: “My thoughts are with the loyal employees of PES Refinery following the company’s decision to close. I will continue to monitor the situation as this process moves forward.” Still no word on whether his thoughts are with the untold and yet-to-be-determined thousands of neighboring residents who’ve fallen ill as a result of two-centuries worth of pollution from PES.

The PES refinery doesn’t sit in Congressman Dwight Evans’ district, but his statement—also on June 26th—did go a little off-script by pushing for “fairness for refinery workers and city residents,” even as it put a little more priority on the post-closure employment situation. But, while he pressed for environmental “remediation” and ensuring city residents didn’t “bear the burden for clean-up,” he didn’t give any indication that he was aware of how bad that refinery had devastated constituent health over the years—and what he’d propose to remediate that.

He did acknowledge that we would need to explore the environmental health aspects. But, he wasn’t eager to venture further into that discussion on WURD’s Reality Check this week. “It’s important to not have a battle between the fate of the workers at the PES refinery and the environmental justice aspects,” said Evans. “I don’t think it’s an either/or.”

About air quality in PhillyLearn Even More

Maybe it isn’t, maybe it is. Area leaders, caught in between two major infrastructure closures, should be concerned about job loss and how that impacts a region that’s always dealing with bad economic indicators. That’s an understandable reflex.

But, that doesn’t mean we have that conversation in total ignorance of the devastating public health, environmental and economic realities that have been an issue for residents long before that explosion. The state of residential health next to and near the PES refinery shouldn’t be a side conversation. No one was concerned about the overall economic health of the city when whole neighborhoods near that refinery were struggling through lost productivity, disability, loss of faculties and the ability to make a living after various illnesses sprung up.

City, state and federal officials need to show concern for both workers and the health conditions of affected residents—before and after the explosion. Officials could be calling for studies, commissions and task forces to examine the years of public health erosion resulting from the refinery, while also finding a way to transition workers into comparable renewable energy jobs (which is not as hard as its being framed so long as you’re committed to clean energy). If we’re talking about remediation and clean-up, the health of surrounding residents should always be a follow-up thought and not relegated to the footnote.

Charles D. Ellison is Executive Producer and Host of “Reality Check,” which airs Monday-Thursday, 4-7 p.m. on WURD Radio (96.1FM/900AM). Check out The Citizen’s weekly segment on his show every Tuesday at 6 p.m. Ellison is also Principal of B|E Strategy, catch him if you can @ellisonreport on Twitter.

Photo via Philly Thrive