Several years ago Lehigh professor Dan Lopresti bought voting machines from various states and counties. He paid a couple hundred dollars for each, finding most at surplus auctions and one off eBay, and among his purchases was a Danaher 1242. That’s the same machine Philadelphia uses.

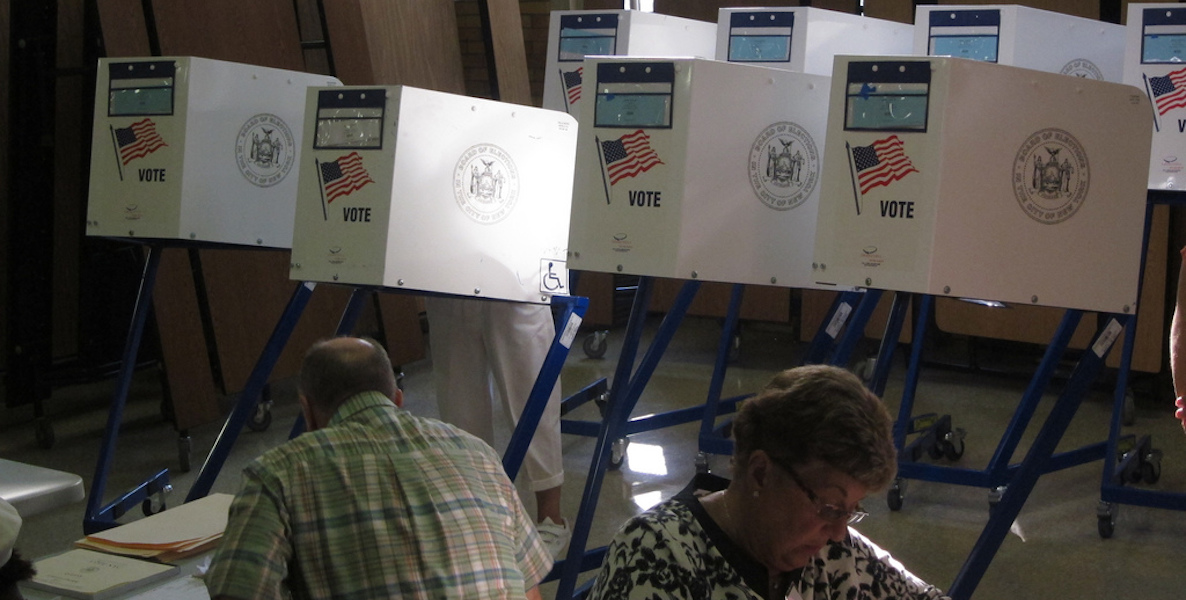

The Danaher 1242 is known as a direct-recording electronic machine, a DRE. Voters press buttons next to the names of candidates they support and push a big green button at the end. The votes are stored on a memory cartridge inside the machine that is programmed by a separate computer before each election. After polls close, the data is removed and connected to another computer — either physically or through a modem — so the results can be tabulated.

The common refrain from local and statewide election officials has been that our voting machines are hacker-proof because they’re not connected to the internet. But their memory cartridges could come into contact with machines that have been, placing them at risk for manipulation.

Somebody who wants to interfere with an election could break into the machine physically and disrupt the program on the cartridge. Such a physical breach of security would prove a daunting challenge. But another option offers easier entry to the machine:

“One thing we have to worry about is whether you could carry what’s effectively a computer virus in the cartridge,” Lopresti says. “All you have to do is infect the one computer programming all those cartridges. Then every one of those cartridges is contaminated.”

He determined, studying a machine right in front of him, what computer scientists and fair election advocates have been preaching for more than a decade, against assurances from election officials: The DRE machines used by Philly and many other Pennsylvania counties could be hacked by just about anyone from anywhere.

Philly got its voting machines in 2002. Many states and counties were rushing to comply with the Help America Vote Act, legislation enacted after the U.S. Supreme Court’s controversial Bush v. Gore decision tipped Florida and the U.S. presidential election to George W. Bush. Our election equipment wasn’t hanging chad bad, but Philadelphia certainly needed a change. Voters were using a pull-lever model of machine first created in 1892. Election workers tallied results by hand, sometimes committing mathematical errors or writing illegibly and throwing off the correct vote total.

These electronic machines were seen as saviors, greatly mitigating the possibility of human error and speeding up the tabulation process significantly. About 83 percent of Pennsylvanians live in counties that use DRE machines similar to Philadelphia.

The common refrain from local and statewide election officials has been these DREs are hacker-proof. After all they’re not connected to the internet. Al Schmidt, the most public-facing of the oft-criticized City Commissioners, notes, “They’re not connected to anything but the power outlet on the wall.”

But risks existed back in 2002, and the same ones do now.

The Department of State has ordered that whenever Pennsylvania counties replace their old machines they must buy new ones creating a verifiable paper record. But counties are not forced to replace their machines by a specific date. And the state didn’t offer a dime to procure new machines. Nor has Governor Wolf banned our current machines, as Virginia has done.

Lopresti explains how hackers the world over have programs or bots constantly scanning computers connected to the internet in any way looking to exploit vulnerable machines. These bots could be programmed to seek computers tied to the election process. And though Philly’s DRE machines are not connected to the internet, their memory cartridges could come into contact with machines that have been, placing them at risk for manipulation.

The cartridges must be programmed on a separate computer before an election. And they must be connected again to a computer for tabulating the results. To be completely free of risk of a hack, these other computers must have never been connected to the internet at any point or had any device, such as a memory stick, inserted into them that’s been connected to the internet.

“The odds a city has a machine like that are probably zero,” Lopresti says.

Schmidt says after the polls close the cartridge is read by a secure machine also not connected to the internet. He said he did not know the specifications of the machine used to program the cartridge, as the process is handled by an outside vendor.

Urge Your Electeds to Fund New MachinesDo Something

Both accusations were devoid of evidence. Yet there is no way to shut down them or any other allegations that should arise with 100 percent authority because individual votes on Philly’s machines leave no paper trail. The only record is stored in the memory of the machine, printed out after a day’s worth of votes. Pennsylvania requires an audit of DRE machines after elections to ensure they accurately recorded votes, but Schneider argues that without the paper trail the audits are meaningless.

“Think about what that word means in other contexts,” she says. “You’re always auditing against, auditing the original transaction versus recorded transactions. The record of the original transaction is missing.”

Alarm bells started sounding about the risk of machines far before the Russian threat. In 2006, a coalition of concerned voters filed a lawsuit against the Pennsylvania Department of State, arguing DRE voting machines should be decertified because of the danger presented by its lack of paper record. The case lasted nine years. The state Supreme Court ruled in favor of the defendants, and the DREs have been allowed to stay.

Public Interest Law Center attorney Ben Geffen, who helped lead the case against the Department of State, says they were attacked for producing a “luddite argument.” As everything else in society was trending digital, they were saying Pennsylvania should return to paper ballots. Despite the backing of computer scientists, their argument proved unconvincing to Supreme Court Justices who, in comparison, had little technological knowledge.

If not next year, then the next opportunity for a roll out would be 2021. So in 2020, when Donald Trump will be running again and fears of Russian interference and who knows what other threats could be ratcheted up further, Philly would be conducting an election with machines that can’t be proven secure.

“The idea that somebody would try to electronically tamper with an election was a little far fetched,” Geffen says. “I think public awareness has caught up since then.”

In February, the Department of State ordered that whenever Pennsylvania counties replace their old machines they must buy new ones creating a verifiable paper record. It’s essentially a phase out, one Susan Greenhalgh, policy director for the National Election Defense Coalition, calls “a weak step in the right direction.” Counties are not forced to replace their DREs by a specific date. And the state didn’t offer a dime to procure new machines. Local jurisdictions rarely replace voting infrastructure without an infusion of federal or state cash because of the high cost. Philly spent about $20 million the last time it replaced its machines, and smaller Pennsylvania counties would likely need a few million dollars.

Perhaps most significantly, Governor Tom Wolf and the Department of State didn’t ban the DREs, as Virginia has done. Last fall, its State Board of Elections enacted a ban and forced 22 local jurisdictions to replace their machines within two months, before the November gubernatorial election.

Stories About Voting in PhiladelphiaRead More

Even with funding, Schmidt says Philadelphia likely wouldn’t roll out new equipment in an election with high turnout, such as this year’s gubernatorial election or a presidential year. The best year for new equipment would have been one like 2017, for the District Attorney and City Controller races. The mayoral election of next year, when funding may be available, would be a slightly less ideal choice but a possibility. If not, the next opportunity for a roll out would be 2021. So in 2020, when Donald Trump will be running again and fears of Russian interference and who knows what other threats could be ratcheted up further, Philly would be conducting an election with machines that can’t be proven secure.

And with an inability to verify each individual vote, a perceived hack in Philadelphia would be almost as effective as a real hack. The Russians are halfway toward manipulating an election just by planting the idea.

“Let’s say they don’t infect the voting machines, but they create the public perception they did,” Lopresti says. “That has the same effect.”

Wikimedia Commons (CC0)