In 2011, Japanese Prime Minister Naoto Kan appeared on television and addressed his countrymen. His government had just botched its response to a national earthquake, tsunami and nuclear disaster, and Kan’s head hung in shame.

“Under the severe circumstances, I feel I’ve done everything I can do,” he said. “Now I would like to see you choose someone respectable as a new prime minister.”

With that, Kan resigned. His shame and act of contrition was not unusual; in fact, five of Japan’s previous prime ministers had similarly stepped down amid popular criticism over the past five years. All were acting in accordance with the Japanese culture of shame, or haji, which calls for leaders to hold themselves strictly accountable when they fail to live up to their obligations.

Change will not come from an outside audit, a toolkit, or even new ethics laws. You can pass all the ethics edicts you want. We need good men and women among us to demand better of those we hire to represent us.

I was reminded of Naoto Kan’s eloquent example upon reading a story on vice. com that asks: “Is Philadelphia the Most Corrupt City in America?” Great, I thought, just what the city needs, another national reminder of our longstanding and well-deserved reputation as “corrupt and contented”—right at the moment we should be trying to reinvent our story for a new generation of citizens. Simultaneously, the specter of Kan looms large in the ongoing saga of our shameless district attorney, particularly as Seth Williams continues to purport to be serving the office and citizens he is alleged to have betrayed—rather than hanging his head and preserving what little dignity he may have left. Yes, we could use an infusion of some haji here, folks.

Where is the shame? Where’s the contrition? It’s not solely our bad actors who act as if perp walks, conflicts of interest, and craven transactional dealings are just a natural part of public landscape; it’s also our leaders who are not ostensibly corrupt, and yet who either remain silent or, worse, refrain from exerting their influence behind the scenes to rid our political life of those who subvert it.

Let’s return to Williams’ continuing insistence on serving out his term while under federal indictment for, among other transgressions, allegedly stealing from his elderly mother. Are you satisfied that, in response, our elected leaders have exhibited moral leadership?

Take a look at the record. On March 21, Democratic party boss Bob Brady said, “I’m saddened, he was a rising star and now he just crashed. I wish he had some type of mentor who could have advised him. Some of these really stupid things that were done were just dumb.” Brady, saying he couldn’t see how Williams could effectively do his job any longer, called on the DA to resign.

Like Brady, Mayor Kenney’s reaction seemed more pragmatic than the product of an inner core that delineates between right and wrong acts: “I don’t see how he can do his job,” the Mayor said. “I think he should resign.”

To his credit, the Mayor’s staff released a statement from him that hit the right notes: “It is deeply shameful that the City’s chief law enforcement officer has been implicated in such a flagrant violation of the law. At a time when our citizens’ trust in government is at an all-time low, it is disheartening to see yet another elected official give the public a reason not to trust us…”

But a written statement released to the media doesn’t quite cut it, does it? It was a start, but shouldn’t Kenney, Brady and other public servants be publicly urging Williams to exhibit some haji—every day, if need be? These guys are powerful men who delight in the reach of their powers—and often use them for good. Did they call Williams and tell him, in no uncertain terms, that it was time for him to ride off into the sunset—for the sake of their city’s reputation? I’m old enough to remember when Senator Barry Goldwater told soon-to-be-impeached fellow Republican President Nixon that the time had come to exit the stage. That was an act of statesmanship, and it’s too often in short supply locally.

But it’s not just Brady and Kenney. Have you heard much from our congressional delegation? For that matter, why hasn’t the Chamber of Commerce put out a statement demanding Williams’ resignation—and telling elected leaders that, if they don’t join in an effort to clean up our politics, they’ll remember such silence the next time such finger-to-the-wind pols come around with their palms out, seeking donations?

As is so often the case in this town, the lack of outrage has been deafening. The Inquirer has called for Williams’ resignation and Black Lives Matter has impressively reacted to news of Williams’ betrayals with full-throated outrage. And then there’s the lawsuit filed by former DA Lynne Abraham and Richard Sprague, seeking to force Williams’ removal from office. I’ve heard the criticism of Abraham, that she’s just getting back at Williams, her onetime protege turned rival. But, hey, I don’t care as much about motive when the act is incontrovertibly a public good; expressing outrage—and shaming—those who seem to so blatantly betray the public trust is an important civic act. We can’t act like these things don’t matter, lest we encourage even more of an outlaw culture amongst our lawmakers.

That’s what the relative silence coming from the political class does. I can’t tell you how many conversations I’ve had with political players the last couple weeks, where, as was the case with Brady and Kenney, the prevailing emotion seems to be disappointment and sadness rather than righteous anger. Poor Seth, what a fall from grace, I’ve heard, complete with a forlorn shake of the head. Then there are those who react with empathy: “Well, he needs the salary to pay his legal fees.”

Seriously? Sorry to get all salty on you, but isn’t that his fucking problem? Look, maybe he can hock what remains of all the goodies he accepted—hell, I’d put a bid in on the $3,212 chocolate couch, just to be able to tell friends the backstory of where they’re sitting. Or how about this: Dude’s a lawyer—let him represent himself.

Our corrupt culture is unique, and it’s easy to forget that when you’re in the throes of the latest scandal. That’s why, beginning today, we’re publishing our Philly Corruption All-Stars, thumbnail baseball card-like profiles of the best, er, worst, practitioners of political black arts, Philly-style.

Of course, what we really need to confront goes way beyond Williams. We need to stare down a longstanding culture of corruption in this town. The specific acts take many forms—there’s the brazen graft Williams seems to have engaged in, there’s the insider sweetheart deals, there’s the legal but insidious transactional culture (think: councilmanic prerogative). What do they all share? A complete lack of haji on the part of our fallen public servants, paired with good people in the system looking the other way.

Our corrupt culture is unique, and it’s easy to forget that when you’re in the throes of the latest scandal. That’s why, beginning today, we’re publishing our Philly Corruption All-Stars, thumbnail baseball card-like profiles of the best, er, worst practitioners of political black arts, Philly-style. Though we’re committed to being a constructive force for making the city better, we think these cards are necessary to hammer home the point that we have a longstanding cultural issue before us.

So we’ll be publishing our all stars by decade—today, we zero in on the 1970s—and we provide you with a link to a pdf version, so you can print the cards out and trade them with your friends:

“I’ll trade you a Fumo for a Cianfrani!”

“Only if you throw in a McCord!”

Of course, we’re having fun with this, but it’s really no laughing matter. Our research for these tongue in cheek posts shows that things have gotten worse, not better. Just think of recent history, and the respective falls of Williams, Kane, Fattah, and McCord—to just name a few. The culture is alive. The virus is spreading.

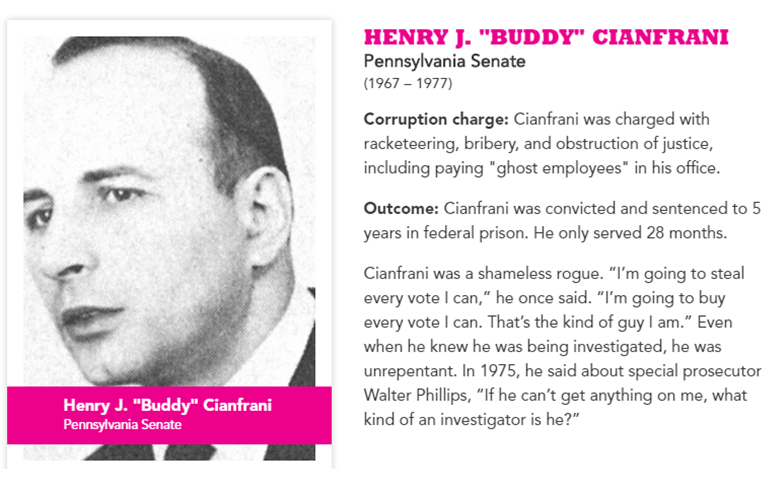

And part of the blame lies with us, you and me. We’ve enabled the type of shamelessness Williams has exhibited, because we’ve long romanticized our corrupt and contented culture. It’s part of our character and many of us—mea culpa—have winked and nodded, trying to hide our smiles, when bad actors dance across our public stage. I’ve written before of how funny I thought it was—so Philly!—when former State Senator Buddy Cianfrani said about special prosecutor Walter Phillips in 1975, “If he can’t get anything on me, what kind of an investigator is he?”

You had to love ol’ Buddy, who finally went away after being indicted on 110 counts of racketeering, mail fraud, obstruction of justice and tax fraud. And when he came out? He went right back to running South Philly. He was a shameless rogue. “I’m going to steal every vote I can,” he once said. “I’m going to buy every vote I can. That’s the kind of guy I am.” He mentored Vince Fumo, who once told me, with a hint of affection and admiration, “I learned from Buddy by being fucked by Buddy.”

When then-City Councilman Jimmy Tayoun spent 40 months in prison in the early ‘90s for many of the same offenses Cianfrani got nabbed for, (there’s basically a playbook), what did he do? He wrote Going To Prison, a guidebook for first time offenders. “Bring a good amount of cash if you can. You’ll see why as you read on,” he writes.

Or, more recently, how about State Senator LeAnna Washington, who berated her chief of staff when he questioned her use of staffers doing political work on the taxpayer dime. “I am the fucking Senator, I do what the fuck I want, and ain’t nobody going to change me,” she said.

Such brazenness actually extends back to well before the decades we’re chronicling in our Corruption All-Stars. If you want to know how far this culture goes back, think back to Republican Mayor Samuel Ashbridge, whose reign of ethical terror ran from 1899 to 1903. According to legendary muckraker Lincoln Steffens, Ashbridge famously said: “I want no other office when I am out of this one, and I shall get out of this office all there is in it for Samuel H. Ashbridge.”

Part of the blame lies with us, you and me. We’ve enabled the type of shamelessness Williams has exhibited, because we’ve long romanticized our corrupt and contented culture. It’s part of our character and many of us—mea culpa—have winked and nodded, trying to hide our smiles, when bad actors dance across our public stage.

The more things change, huh? Now you see the antecedent of Williams, Fattah, Kane, and all the others. The more you dive in, the more you realize it was ever thus: Betrayal of the public trust flourishes when good men and women in the system shrug and look the other way.

Here at The Citizen, we’re always looking for solutions, so in the past, I’ve married the litany of perp walks and ethical transgressions that dominate our headlines with innovations like the Netherlands Court of Audit, akin to our Congressional Budget Office, which tries to promote integrity in government rather than just punish corrupt politicians. Or there’s Transparency International, which publishes a Local Integrity Systems Assessment Toolkit that explains how they work with local governments and civic partners to bolster integrity.

But change will not come from an outside audit, a toolkit, or even new ethics laws. You can pass all the ethics edicts you want. We need good men and women among us to demand better of those we hire to represent us. And when our public servants do fall short, we ought to demand that, before lawyering up, they look to the far east, take note of men like Prime Minister Naoto Kan, and sign on for a prompt infusion of haji.

Header photo by Angie Chung via Flickr