In just eight percent of the city’s land area, at the center of the region’s transportation network, Center City and University City hold 370,000 jobs, 53 percent of the city’s total. Densely developed, these places host a substantial share of the region’s universities, hospitals, corporate headquarters and tourist destinations. They house 37 percent of the new residents who moved into Philadelphia since 2010. University City attracts students, research dollars and invests in innovation. Downtown’s economy is diverse; it’s thriving with arts, culture, retail and restaurants and brimming with well-educated workers who are drawing employers back from the suburbs.

A few thousand high-end condo units added since 2001 stand out as symbols of change and, sometimes, objects of resentment. Yet, more than 90 percent of developed land downtown is occupied by office towers, hospitals, hotels, colleges and retail shops. Two-thirds of jobs in these buildings do not require a college degree; one-third need only a high school diploma. SEPTA enables 150,000 Philadelphians, 25 percent of working residents of every city neighborhood outside Center City, to connect to these jobs each day. This is the largest and most diverse center of employment in the region.

It is not that Philadelphia taxes too much, we tax the wrong things; 63 percent of the municipal budget comes from taxing what readily moves, namely employee salaries and business revenues. Despite recent increases, we still under-rely on the property tax and pay the price with underfunded schools.

Pull the camera back to Philadelphia’s 135 square miles and you find working-class, middle-class, and some upper-income neighborhoods, but quickly confront the central challenge: the highest poverty rate (25 percent) of America’s 10 largest cities.

Here, children may grow up without opportunity, without skills needed to compete in the 21st century economy. More than 80 percent of the city’s 127,646 low-income renter households pay a disproportionate share of income on housing, leaving less for food and clothing. Federal subsidies are declining. Homeowners with limited means cannot afford repairs, so their properties deteriorate. Diminished purchasing power causes quality grocery stores to avoid many neighborhoods. The opioid crisis further destabilizes communities, driving a new surge in homelessness.

A PROBLEM OF JOBS

Poverty is not a scourge like a biblical plague. It is neither fate, nor a fact-of-life. Poverty ballooned in the 1970s as Philadelphia began hemorrhaging 300,000 jobs over the next three decades. From 1970 to 2015, the city added 100,000 people living in poverty—2,200 per year born, falling into, or arriving in poverty. Yet, in those same years, Philadelphia lost more than 500,000 working-class and middle-income residents—about 11,000 per year—departing for suburbs where jobs expanded by 110 percent. So Philadelphia’s high poverty rate results in part from losing five times as many working- and middle-class residents as new poor people added. This does not minimize the magnitude of poverty, it only highlights that this is a problem of jobs.

Mayor Kenney’s focus on education is an essential part of the cure, equipping young people with skills to be competitive. Yet, only 27 percent of the city’s households have school-age children and the strategy presumes available jobs—lots more of them—in a city that is growing more slowly than 23 of America’s largest cities.

The sooner we get beyond the politics of resentment and cease pitting downtown against neighborhoods, wealth against poverty, the sooner we can tell a tale of one city, despite polarization at the national level, that’s come together around a citywide agenda for dynamic and inclusive job growth.

Since the recession, most American cities have outperformed the national economy. Philadelphia has not. New York and Boston, which lost the same percent of manufacturing jobs as we did in the last quarter of the 20th century, have since rebounded, respectively adding 14 percent and 24 percent more jobs than they had in 1970. Philadelphia has 24 percent fewer jobs. We’ve barely returned to 1990 job levels. Cities with higher rates of job growth usually have lower rates of poverty.

THIS IS NOT A TALE OF TWO CITIES; IT IS A TALE OF ONE CITY THAT IS NOT GROWING FAST ENOUGH.

We lag not only in jobs, but also in housing production. What’s termed a “boom” in Center City places us 62nd in housing construction among the nation’s 100 largest counties. Still, the disparities are painful for all to see between areas of growth and those with continuing job and population loss. In major portions of several City Council districts, poverty rates are over 40 percent. This is the compelling challenge Philadelphia must address.

![]()

However, several cures recently proposed would exacerbate the problem. Many seek to compensate locally for lost federal revenues for income redistribution and housing subsidies by adding to the cost of doing business or developing in the city. A recent report by the City Controller, however, highlights that the economics of housing production work in only 30 percent of the zip codes in the city; in the other 70 percent, incomes do not come close to supporting the rents or mortgages required to underwrite rehab or new construction. While there are ways to lower Philadelphia’s construction costs, the affordability challenge does not derive primarily from overpriced housing—rents are the lowest among big cities in the Northeast. The problem is that incomes are too low.

Federal taxation spreads the burden for redistribution across all localities. Likewise, recent cuts to marginal tax rates affect all 50 states. When legislating locally, however, one size does not fit all. Mandatory inclusionary zoning and impact fees may be supportable in San Francisco, which added jobs at the rate of 3.6 percent per year since 2009. Seattle’s growth rate is 2.4 percent. Philadelphia has averaged job growth of just 1.4 percent per annum; so accentuating differential costs between city and suburbs can be counterproductive, especially this late in the business cycle.

ACCELERATING GROWTH

What does it take to accelerate job growth and raise incomes locally? The majority of employers in the post-industrial economy have choices. They can locate anywhere and yes, they choose places with great amenities and thousands of recent college graduates. However, facing global pressures, they also require a competitive business climate and attention to the quality of public spaces and walkways.

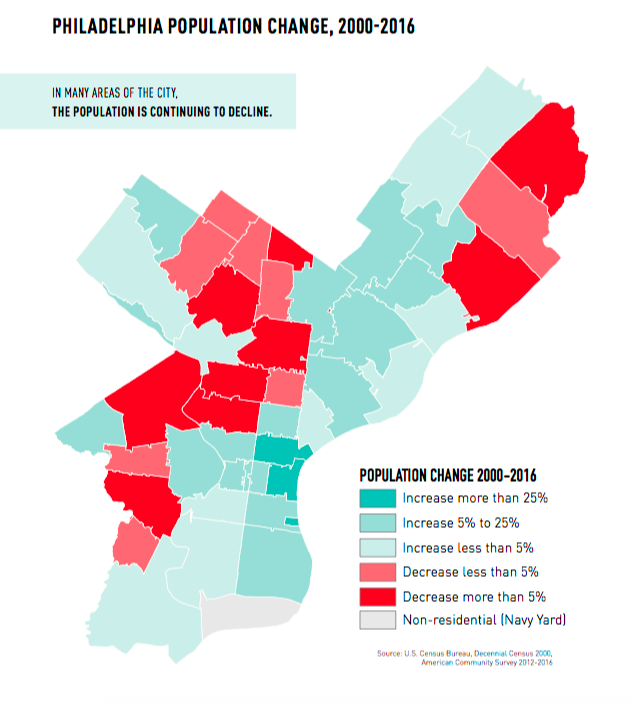

The obsession with gentrification in a handful of neighborhoods is blinding reporters and analysts to the obvious: in many neighborhoods, the old trend of working-class and middle-income households departing for the suburbs continues.

Philadelphia’s wage tax, despite substantial reductions from 1996 to 2008, is still almost four times the regional median and the City recently slowed its rate of reduction dramatically. We are the only large city to have a business tax on both gross revenues and net income. Regionally, the Business Income and Receipts Tax (BIRT) has no counterpart, adding a 20 to 50 percent premium on downtown occupancy costs. This is an era of corporate downsizing and cost-conscious consolidation.

![]()

Nonetheless, office buildings remain in most cities the densest containers of jobs—the highest wage and the most diverse offerings—including maintenance, security, janitorial, engineering, construction, technical and office support functions. Office buildings hold 40 percent of Center City’s jobs. Among the 20 largest cities, Philadelphia is just one of two (along with Baltimore) with fewer office jobs than in 1990, down 2 percent. New York is up 2 percent in office jobs, Chicago +3 percent, Boston +5 percent, Atlanta +9 percent and Charlotte +12 percent.

Philadelphia has a history of self-inflicted wounds. In the 1970s, de-industrialization, suburbanization and inner city redlining cost us 164,457 jobs and 260,399 residents. At the same time, local government more than doubled the wage tax from 2 percent to 4.3 percent, cresting at 4.96 percent by 1990. People and jobs departed, the tax base shrank, but rates were continually raised with few efficiencies achieved in government. This pushed more employers and workers out of the city.

It is not that Philadelphia taxes too much, we tax the wrong things; 63 percent of the municipal budget comes from taxing what readily moves, namely employee salaries and business revenues. Despite recent increases, we still under-rely on the property tax and pay the price with underfunded schools. What’s required is a shift from taxing what moves to relying more on immobile land and improvements.

COMPETITIVENESS AND QUALITY OF LIFE

After 50 years of decline, job growth in Philadelphia started only after the City began significant reductions to wage and business taxes in 1996. Prior to passing the 10-year tax abatement in 1997, Philadelphia produced less than 3 percent of the region’s housing units. In the decade after, we jumped to a 10 percent regional share and began to add residents. Since 2010, 25 percent of the region’s housing starts have been in the city, with 55 percent of those in Greater Center City. Of course, demographics are helping, but construction numbers need to work to attract investment capital.

So too in the 1990s, all major cities discovered that when they focused on minor infractions, quality-of-life crimes and disorderly behavior, while providing help for those in need, serious crimes declined. Quite simply, a city can be compassionate and still set standards for reasonable behavior on the street. It was only after business and residential areas became safe in the 1990s that population and jobs began to rebound. Too many take today’s vibrant Center City for granted when it rests in part on a buoyant national economy and demographic trends that won’t last forever.

AN OLD, CONTINUING STORY

When poverty and income statistics were released last month, there was much consternation that the city’s poverty rate barely budged, while experts puzzled about incomes that seemed to fall. This is because the obsession with gentrification in a handful of neighborhoods is blinding reporters and analysts to the obvious: in many neighborhoods, the old trend of working-class and middle-income households departing for the suburbs continues.

Despite success downtown in the last eight years, 62,000 more residents of city neighborhoods departed for homes in suburbs than moved in. Only local births, immigration and downtown growth kept us population positive. People follow jobs: outside Center City, 211,000 Philadelphia residents (40 percent of the workforce) reverse commute to suburbs each day. Since suburban employers are obligated to withhold the full wage tax from city residents, there’s a significant incentive (a 3 percent salary increase) for reverse commuters to find homes closer to their jobs. Incomes for remaining residents don’t need to fall for average wages to decline. All it takes is for the population to decline when upwardly mobile, working- and middle-class families depart.

High taxes, slow growth and deteriorating quality-of-life issues are not just a problem for downtown; they erode the base of many neighborhoods across the city.

The sooner we get beyond the politics of resentment and cease pitting downtown against neighborhoods, wealth against poverty, the sooner we can tell a tale of one city, despite polarization at the national level, that’s come together around a citywide agenda for dynamic and inclusive job growth.

Paul R. Levy is the president of the Center City District. This column first ran in the Center City Digest, the newsletter of the Center City District.

Photo: Night Lights and Cityscape in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Photo by Public Domain Photo via Good Free Photos