Where you live is of supreme importance in America. Your address is a factor in what schools your children can attend, the jobs within reach, the value of your home or the price of your rent, the quality of your air, and much more. Your neighborhood is also your social network, your community and often, part of your identity. Yet not all neighborhoods are equal: some have better or worse schools, higher quality or subpar housing, more or less access to transportation and jobs, and other forms of inequality. These neighborhood divisions are often the result of segregation by race and class, influenced by governmental policies like redlining, mortgage discrimination and urban renewal.

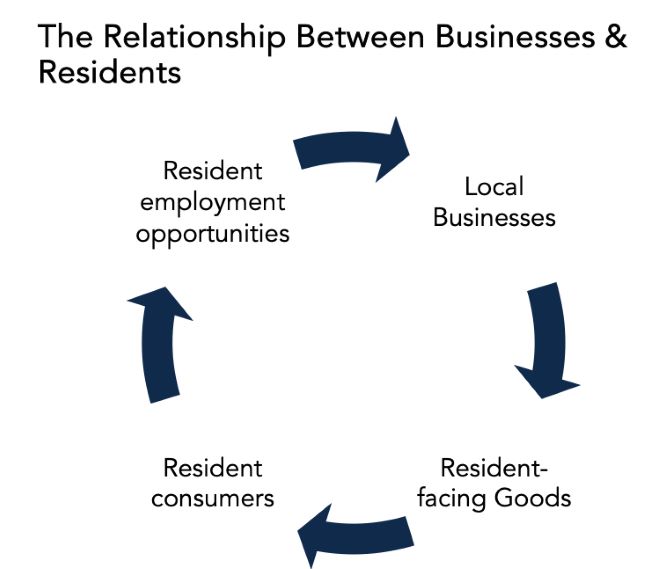

However, neighborhoods are not static. Over the past 50 years, some neighborhoods that were once derelict have been revitalized. Other neighborhoods that were once prosperous have fallen into disrepair. These neighborhood changes impact existing residents, as some who wish to stay in the neighborhood are displaced, either through investments that make the neighborhood too expensive or through declining conditions that make staying all but impossible. In turn, this changes the retail composition of the neighborhood, as new businesses may or may not cater to existing residents — and new residents may or may not patronize existing businesses. This symbiotic relationship between small businesses and neighborhood residents is a key feature of all neighborhoods but is especially important in ethnic enclaves.

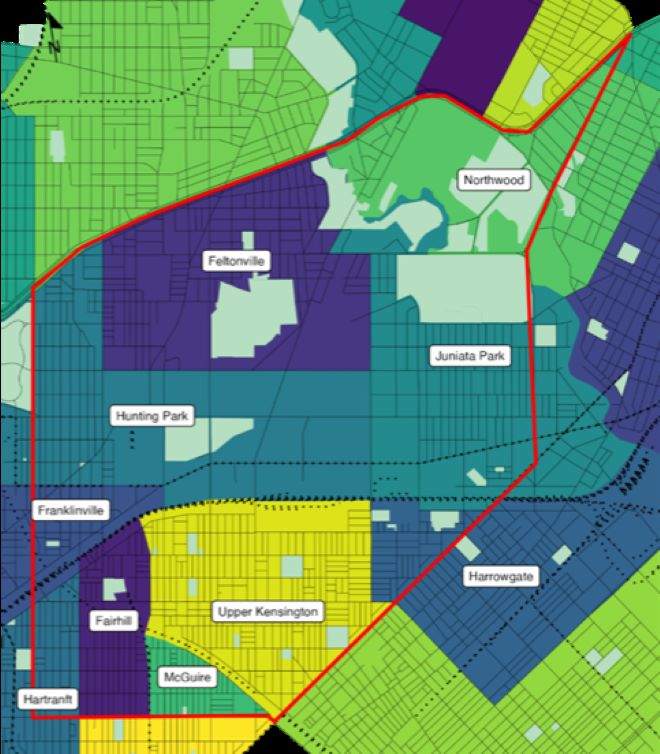

Neighborhood-based nonprofits like Nueva Esperanza in Eastern North Philadelphia try everyday to make disadvantaged neighborhoods communities of opportunity, where disparities in wealth, income, and health can be remedied and where residents can choose to remain in place no matter the pressures that make this difficult. To that end, the Nowak Metro Finance Lab at Drexel University, Reinvestment Fund, and the Aspen Institute Latinos and Society Program have spent the last year working with Esperanza to develop an anti-displacement strategy for Eastern North Philadelphia, a majority-Latino part of Philadelphia composed of eight neighborhoods. This project, supported by the Comcast NBCUniversal Foundation, led to a Community Preservation Toolkit as part of a report titled “Community Preservation in Latino Eastern North Philadelphia.”

Below, we describe our strategy. For more detail, please see our full report. The anti-displacement strategy contains three signature initiatives: a residential, rental land trust, a commercial land trust, and a community preservation district. To make these three initiatives a success, our team developed a Community Preservation Toolkit, outlining six state and local policies, six state and local programs, and six strategies for Esperanza to implement.

Contextualizing Eastern North Philadelphia

Eastern North Philadelphia, which spans five square miles, has a total population of approximately 100,000 people, or 6 percent of Philadelphia’s overall population. Around 67 percent of the households identified as Hispanic or Latino, according to the American Community Survey, while Philadelphia as a whole is only 15 percent Latino. The median household income in the neighborhood is extremely low: $27,000 per year in 2019. Philadelphia’s area median income, as calculated by HUD, was approximately $90,000. However, this number is skewed upwards by wealthy suburbs surrounding the City of Philadelphia; the city’s median income was $46,000. This means that housing affordable to those making 30 percent of the area’s median income would be affordable to the median resident in Eastern North Philadelphia.

The neighborhoods in Eastern North Philadelphia remain the most low-cost in the city of Philadelphia, but they are still rapidly appreciating. Since 2019, many areas in Eastern North Philadelphia have had asking rents increase by more than 25 percent, compared to 16 percent citywide. Similarly, house prices have increased by more than 40 percent in much of Eastern North Philadelphia, compared to a 30 percent increase citywide. Nonetheless, Eastern North Philadelphia housing values and incomes remain in the bottom quartile for the city. Our quantitative displacement risk analysis shows limited signs of gentrification but does find characteristics of a population at risk of displacement should housing prices continue to rise.

We don’t dispute that these neighborhoods need investment and growth. However, it is important that policymakers and practitioners focus on the right kind of investment.

Philadelphia is a city of commercial corridors, and Eastern North Philadelphia is no exception. There are 15 commercial corridors recognized by the City of Philadelphia that are contained within, or intersect with, the area we study. We focus on four significant commercial corridors: 5th and Lehigh, 5th and Roosevelt Boulevard, Front and Allegheny, Rising Sun and Wyoming. Around 90 percent of the businesses on these commercial corridors are small businesses, with over 1,200 employees. 77 percent of the independent businesses on the corridor are business-to-consumer (B2C) firms, and 90 percent of those independent B2C businesses are in locally serving (compared to traded) industries.

These commercial corridors contain many vibrant businesses, with many retail establishments, restaurants, churches, and entertainment venues. Many of these businesses are deeply tied to the residents currently living in Eastern North Philadelphia, with retail, food, and cultural amenities serving the largely Latino population of Eastern North Philadelphia. As such, a small business preservation strategy must also include a residential preservation strategy because the businesses currently serve the residents who live in the community.

Initiatives to address residential & commercial displacement

Esperanza has proposed three initiatives to mitigate displacement risks in Eastern North Philadelphia. Two initiatives, a residential trust and a commercial trust, will be spearheaded by Esperanza, in order to support residents and businesses. The third initiative, a new city-designated district, would aim to provide increased support to small and legacy businesses located in the designated geography.

- The Stable Affordable Rental Trust (START), a rental-based community land trust aiming to provide housing to households earning less than 60 percent AMI. START will pair affordable rents with an individual development account to aid with wealth-building.

- A Commercial Corridor Trust (CCT), for properties on key Eastern North Philadelphia commercial corridors. Esperanza will aim to purchase key commercial properties and provide below market-rate rent to local, resident-focused small businesses.

- A Community Preservation District (CPD), designated by the City of Philadelphia, would provide additional resources to small and legacy businesses within the District. The CPD would also be designated a “Neighborhood Serving Retail Zone” to encourage small and local stores in lieu of big box chain stores.

A community preservation toolkit

In order to make the three initiatives a success, we highlight 12 city and state policies and programs that need to be expanded, reorganized, or created. Additionally, based on other national efforts, we recommend that Esperanza implement or expand six complementary strategies to bolster their support of residents and business owners. Because many of these programs are specific to Philadelphia, in this newsletter we sketch the broad principles guiding the policies, programs, and strategies that we recommend:

- Support for non-profit acquisition of real estate

At the end of the day, the ability for local control of local real estate is central to an anti-displacement fight. This means that residents and community-based non-profits need to be supported in their desire to acquire residential and commercial real estate, before gentrification rapidly increases property values. Such support is especially important now, in the face of parasitic capital that has entered low-income communities throughout the last decade. Support for residents and non-profits to acquire real estate can come in many forms, and a multi-pronged approach is often necessary. For Philadelphia, we recommended increased support to city-wide programs and policies that provide operating expenses to community development corporations, create targeted acquisition funds available to non-profits and legacy businesses, and enact tenant and community opportunity to purchase when buildings go up for sale. These direct programmatic supports and necessary policy supports make it more likely that residents and non-profits can buy buildings when they become available, helping to ensure that residents and businesses can stay in place.

- Support for residential and commercial tenants

As residential and commercial tenants face rising costs, including increasing house values, skyrocketing rents, and accelerating property values, they need help to remain in their communities. This help can come in many forms, including direct support to tenants through rental subsidies, emergency housing assistance, and tenant protections. These programs and policies ensure that tenants can cope with short-term spikes and hardships, while tenant protections discourage the worst sort of predatory behavior on the part of landlords and investors. Tenant protections and financial support to both residents and small businesses can ensure that those who wish to remain in a community can continue to afford to do so, even as that community may change in drastic ways.

- Support at the intersection of local residents and legacy businesses

Our third initiative, a Community Preservation District, is based on similar initiatives in Illinois and San Francisco. In Philadelphia, we’ve recommended that a Community Preservation District be designated based on the cultural importance and the threat of displacement. Businesses located in the district would be eligible for preferences from the local and state government for new and existing programs, and it would be combined with zoning changes that preference small, resident-serving businesses. These community preservation districts are based on a recognition that, in many tight-knit ethnic communities, there is a symbiotic relationship between residential patterns and small business success. By recognizing this relationship in the form of a clearly designated district, the support for both small businesses and residents can be channeled in such a way as to encourage a greater impact than if support were directed at either small businesses or residents alone.

Conclusion

The set of challenges affecting Eastern North Philadelphia’s residents and small, locally owned businesses are familiar across similar neighborhoods facing deep poverty and disinvestment. Local policy regarding such neighborhoods doesn’t typically focus on affordable housing or small business preservation, but rather on new investment and economic growth. To be clear, we don’t dispute that these neighborhoods need investment and growth. However, it is important that policymakers and practitioners focus on the right kind of investment. Community-centered investment that prioritizes cultural preservation, community wealth building and anti-displacement is crucial for Eastern North Philadelphia and neighborhoods like it. On federal, state and local levels across the country, we need to cultivate policy that makes these types of investments possible, so that these neighborhoods are equipped in a quickly evolving real estate market and socioeconomic landscape.

Bruce Katz is the Founding Director of the Nowak Metro Finance Lab at Drexel University. Reverend Luis Cortés is the Founder, President, and CEO of Esperanza. Benjamin Preis and Elijah E. Davis are Research Officers at the Nowak Lab. Avanti Krovi is a former Research Officer at the Nowak Lab.

![]() MORE FROM BRUCE KATZ AND THE NOWAK METRO FINANCE LAB

MORE FROM BRUCE KATZ AND THE NOWAK METRO FINANCE LAB