From my perch in Philadelphia, I was a bit gobsmacked when I heard the news last October that downtown Pittsburgh was getting $600 million in new investment. The money will go toward converting office buildings, creating and renovating public spaces, and improving the downtown’s public realm. Philadelphia and Pittsburgh have a bit of a sibling rivalry, and like my sons who can’t stand it when one gets something the other does not, the news left me wondering: Where’s Philly’s money?

The truth is that Philadelphia has been converting office buildings into apartments since the 1990s, encouraging tens of thousands of people to live downtown (which has only increased since the pandemic). Philly’s live-work-play downtown is often seen as a model for cities trying to escape the urban doom loop.

That said, Pittsburgh has done something Philadelphia and most other cities have not: united its leaders and funders around a vision for downtown. While much of Philadelphia’s Center City west of Broad Street has bounced back, the lack of a vision for Market East is all the more apparent now that a new stadium is out of the equation. Could Philadelphia unite its local and regional leaders around this lagging part of downtown as Pittsburgh did with theirs? There are lessons for Philly (and just about every other downtown) in Pittsburgh’s fundraising, approach and scale.

Taking collective action

One of the most impressive things about this investment in Pittsburgh’s downtown is the number of investors and stakeholders involved in making this work happen. This is what collective action looks like. According to a PA.gov press release here’s how the $600 million came together:

As part of this effort, the Shapiro Administration is investing $62.6 million and the City of Pittsburgh is committing $22.1 million through the Urban Redevelopment Authority.

A broad coalition of private sector leaders and regional foundations have committed more than $40 million — and counting — in additional funding for this plan, including partners like BNY; Dollar Bank; Duquesne Light Company; Federated Hermes; FNB Bank; Giant Eagle; Highmark; Pitt Ohio; PNC Bank; PPG Industries; Reed Smith; Buchanan Ingersoll & Rooney PC; K&L Gates; the Buhl Foundation; the Eden Hall Foundation; the Heinz Endowments; the Hillman Foundation; the Jewish Healthcare Foundation; the Pittsburgh Steelers; the Pittsburgh Pirates; and the Pittsburgh Penguins. Those public and nonprofit dollars will help spur an additional $376.9 million in private sector investment from real estate developers Downtown.

Aaron Sukenik, vice president of district development at Pittsburgh Downtown Partnership, notes the importance of the Allegheny Conference on Community Development in bringing local and regional leaders together. They’re the ones who have published the actual vision.

As Allegheny Conference CEO told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette [paywall]: “We all know we’re in an environment right now where there are so many issues and so much noise, and what you have to do is figure out what those three or four things are that everybody agrees upon … We’ve built trust that we would all be there and show up and that we could take action in a coordinated way.”

The Allegheny Conference serves a role somewhat akin to a Chamber of Commerce, but notably the Conference emanated not from a concern about the business community, but for transportation and the environment. Several philanthropies also sit on the board. The result is that there’s skin in the game from local, county, state, corporate, and philanthropic sources and a sense that this is a community vision, not just that of the biggest power players.

Creating a multidimensional neighborhood

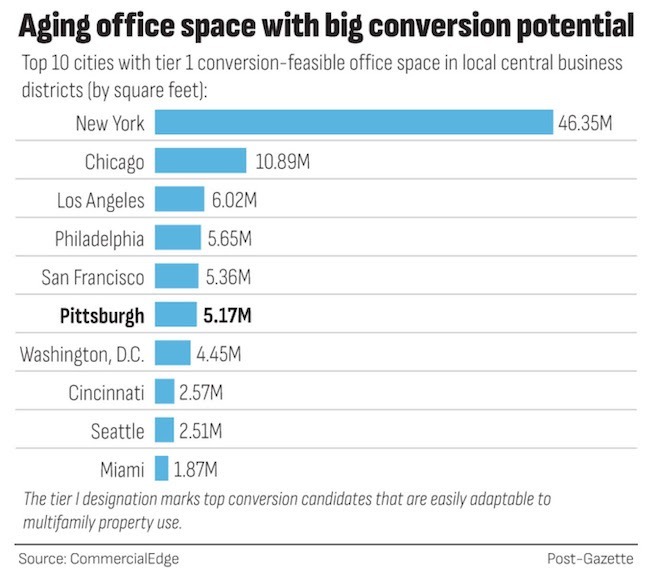

Perhaps even more so than Philadelphia, Pittsburgh’s downtown was over indexed on commercial real estate before the pandemic. The core of this revitalization plan will be focused on commercial-to-residential conversions.

Sukenik estimated that while Pittsburgh has nearly 25 million square feet of office space, somewhere between 5 and 11 million square feet of office space can be converted. “That’s further helped by the fact that we have an old downtown. We have a lot of Class B and C office in our downtown. It was built a hundred years ago, give or take 30 years,” Sukenik says.

Last fall, seven major conversions were announced, using $501.1 million in combined capital to create or preserve nearly 1,000 residential units. Nearly one third of the units are expected to be affordable to low- and moderate-income residents.

Of a city of 300,000, Pittsburgh has approximately 7,000 people living in its core downtown and double that in the greater downtown area. Philadelphia’s core Center City has more than 60,000 residents, by comparison. For both Pittsburgh and Philly, adding more residents is key to a virtuous cycle: More residents bring foot traffic for retail, more eyes on the street to beat back social disorder, more employees who can walk to the office.

A public realm suited to post-pandemic trends

If it sounds like this is just about office conversions, a big focus of the downtown plan is on public spaces and improved streets.

With $30 million in funding, acres of underutilized parking lots will be transformed into a new civic space called the 8th Street Block. According to PA DCED, “Led by the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust, the 8th Street Block project includes plans to build an outdoor recreational space with amenities that could include a green open lawn with outdoor games, a water play area for families, and an amphitheater to accommodate public events.”

Market Square, which has served as a public space since the 1700s, will be renovated to enhance its programmable space.

And the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania will invest $25 million into a series of short- and longer-term projects that will improve pedestrian access to and activities in Point State Park. This work should be done in time for the 2026 NFL Draft, when Pittsburgh will host hundreds of thousands of tourists. Not to be outdone, Philadelphia too has been planning for 2026 — the country’s semiquincentennial / 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, with World Cup matches and the MLB All-Star game — for years. The National Park Service has embarked on a $85 million revamp of parts of Independence National Park that includes the reopening the First Bank of the U.S., restoring Welcome Park, sprucing up Benjamin Rush Garden and adding the Bicentennial Bell, and $14 million in conservation-minded HVAC upgrades). But so far, the City hasn’t announced much of anything to do to Market East, the corridor between City Hall and the Park, in the runup 2026.

The Pennsylvania Council on the Arts has also designated downtown Pittsburgh as a Creative Community and allotted $400,000 for the city to hire an artist-in-residence to coordinate the activities of the creative economy. This includes structuring new programming for local artists, performers, musicians, and other creative entrepreneurs over the course of the next four years.

Adding retail and addressing disorder

Finally, the vision involves some support for addressing two key indicators of post-pandemic decline: retail vacancy and increased social disorder on the streets. The Pittsburgh Downtown Partnership will recapitalize its small business support programs to provide rent abatements for new small businesses looking to locate in the downtown core.

Streets are also getting some love. Increased drugs and mental health concerns have provided the impetus for an additional 750,000 square feet of sidewalks and alleyways to be cleaned and maintained with new program funding.

The Steelers, Penguins, and Pirates — both the Steelers and Pirates have stadiums downtown; the Penguins play 2.5 miles away, uptown — are supporting additional police patrols, services for those with mental illness or drug addiction, and the creation of a dedicated youth violence intervention team.

Though not part of the October announcement, once-premier shopping street, Smithfield Street, is set for a redesign that will begin in 2025. Sidewalks will be widened by several feet, landscaping will be added, intersection bump-outs will help pedestrians cross traffic, and better lighting will improve the street’s safety and appearance.

Aligning politics

A failing downtown favors no one. Pittsburgh’s Mayor Ed Gainey is running for re-election in 2025, and Gov. Josh Shapiro is running for re-election in 2026. I’m sure they both realized downtown Pittsburgh could not die on their watch.

By contrast, if this revitalization effort is successful in producing some quick wins, it stands to provide an example for how regional leaders can come together for the shared benefit of their community. With moves like these, cities can shift the conversation from decline to stability and even growth.

In this strange moment where everything feels tainted by ideology, this work of rebalancing a city’s real estate portfolio, making it easy for small businesses to locate downtown, improving the public realm for residents and tourists, and youth violence prevention all feel like relatively straightforward, politically neutral winners — even for decidedly blue big cities like Pittsburgh and Philadelphia.

The only question then is: Will it be enough?

Diana Lind is a writer and urban policy specialist. This article was also published as part of her Substack newsletter, The New Urban Order. Sign up for the newsletter here.

![]() MORE FROM THE NEW URBAN ORDER

MORE FROM THE NEW URBAN ORDER