For the month of February, a Philadelphia man will live in an open air mock jail cell. At night he’ll sleep in a body bag. During the day he’ll speak and listen to anyone who steps up to the bars. Visitors will find a thin, deep-eyed man who at 42 years is neither young nor old, radiating love.

The man in the cell is Michael “OG Law Law” Ta’Bon, and the “Deathfast,” as he calls it, is entering its seventh year as an annual campaign of art, performance, music and activism aimed at disrupting the birth to prison pipeline.

Produced in partnership with the Philadelphia Anti-Violence Coalition, the Deathfast is among Ta’Bon’s highest profile acts, but it’s no one-off. Constantly creating, Ta’Bon is an artist. Activism is his medium, and battle-ready love is his subject. From this subject, he has no distance. “I fight the Devil,” he says.

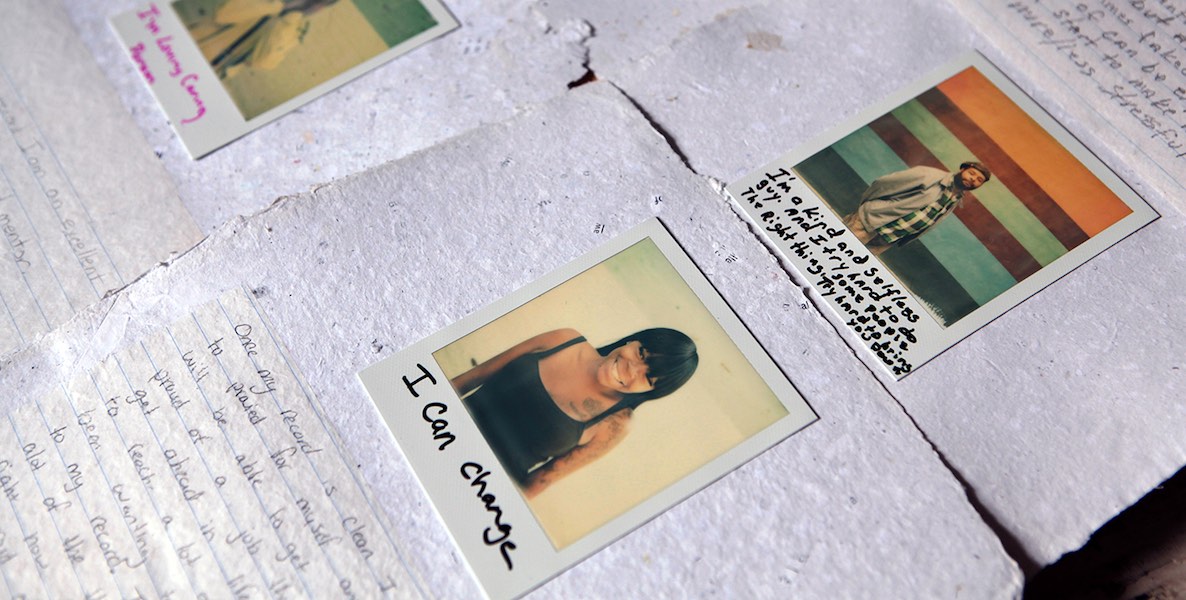

Ta’Bon is vitality in search of form. In his room in a semi-derelict stone house at the bottom of Germantown Avenue, he’s penned lyrics, sketches and inspirations in a 360-degree storm of Sharpie and pencil across the bare sheetrock of his walls. Sixteen bars of a spare beat to a song-in-progress loops endlessly from his computer. Art supplies are scattered across the floor.

On this morning in mid-January, OG Law Law is getting dressed to go out and draw in public. I’ve offered to drive. He slips his wiry torso into a fresh t-shirt, dons a hoodie, and steps into his jail suit: orange coveralls that announce prisoner.

He zips up and drapes around his neck a length of shackles, chains complete with hand- and leg cuffs. We head for the door.

Ta’Bon got his first sentence at the age of 16 on a car theft charge. By his own account, he was a stickup kid, a barber and a drug dealer. At 24, he robbed a Clover store on North Broad. Approaching the register, he raised his shirt to show a pistol tucked into his belt. Caught and convicted, Ta’Bon served seven years before being paroled in 2005.

In prison, he discovered a talent for writing, and became the go-to-guy for a letter that would earn you leniency from a judge, or new Timberlands from your girlfriend. His first book-length endeavor was erotica. Released from prison with a manuscript in his hand and a headful full of rhymes, Ta’Bon spun his incarcerated past as a promotional angle. He put on the jail suit and adopted the pen and M.C. name “XXX Con.”

When Ta’Bon listens, all channels are open. He meets your eyes, nods, and greets your truth. It’s on you to match his honesty. This is Ta’Bon’s gift. He’s an injured man with strength, a man in chains who is radically free, and his presence challenges you to be better.

He came out to witness rising violence; 2006 was one of Philadelphia’s deadliest years in decades. One evening, in the final moments of a basketball game at a community center, Ta’Bon saw a child shot to death.

Shaken, Ta’Bon conceived a remembrance in the style of the Vietnam War Memorial in D.C. and soon after led the painting of the Rest in Peace Memorial Wall at 1924 Hunting Park Avenue.

He painted 406 names, Philadelphians murdered in 2006. Some had been his friends. The jail suit he wore ceased to be schtick. He was harnessing the injuries of his community, of his own life, and finding purpose. Organized by month, the names form eight columns spanning the sidewall of a two-story rowhome. On a clear day, the sky matches the mural’s underlying field of blue.

Ta’Bon completed the wall in March 2007. Murder, however, was not done with Ta’Bon. On January 19, 2008, Ta’Bon’s girlfriend, Chanté Wright, was killed, probably as retaliation for stepping forward to testify about a murder she’d witnessed.

Another blow came on the heels of Wright’s death: In September 2008, then Governor Ed Rendell placed a moratorium on parole following the murder of police officer Patrick MacDonald. Ta’Bon, who was a parolee, got temporarily sucked back into prison. In despair, Ta’Bon asked God for guidance, and God replied.

“He told me to do a thing,” Ta’Bon says in a soon-to-be released documentary. “Love.”

Ta’Bon adds, “… and wear this dumb-ass jail suit while you’re at it.”

Months later, jail suit on, Ta’Bon returned to the RIP Wall, built a cell, working straight through an ice storm, and held the first Deathfast.

To follow God’s command, Ta’Bon knew he could not turn away from the death and confinement that had marred his life. Freedom lay on the other side of that pain, and love was the only way through.

The current iteration of Ta’Bon’s “Un-Prison Cell” sits in an empty lot on the corner of 22nd and Bellevue. It’s a 20-foot trailer with faux-cinder blocks and painted flames. The trailer is divided in two: A 6’x8’ portion makes the cell itself, complete with bars and a cot; the larger half is the “commissary,” which will house a DJ booth during the Deathfast events.

This year, the Deathfast is linking up with schools, businesses and non profits to create a roving, celebratory manifestation of love conquering pain, touting Education over Incarceration. The tour will start at Germantown and Logan, the epicenter of a shootout last June that left four people injured, and will move to anywhere there’s gun violence in the course of the month. (You can follow Ta’Bon’s journey on his Facebook and Twitter feeds.)

As in other years, Ta’Bon will tell his stories to each and every person who approaches him—parents who bring their troubled children, cops with kids hanging out on the corner, parole officers with their parolees. It’s in his stories that he’s most powerful, bringing an honesty and love to life, despite all its sadness.

Ta’Bon points to mold streaking downward from the ceiling of the cell. “See that? We got water damage,” he says. A moment later, he’s climbed onto the roof to inspect, but his phone rings and he’s pulled into a long, twisting conversation. The call is about his kids, and it’s the sort of call perhaps familiar to anyone who’s navigating the breakup of a marriage. As you might imagine, the habits of a performance artist activist on a mission from God with no steady stream of income make for a complicated life.

Ta’Bon climbs down from the roof, bids thank to his man across the street—a burly, Philly-bearded dude in a black hoodie who keeps an eye on the Un-Prison Cell—and we head for Center City.

We wind up across from Dilworth Plaza on the cold, vacant stone by the subway entrance. The area is rich with the lore of OG Law Law: In October 2012 he chained himself to the LOVE sculpture for a week, exposing himself to the full fury of Superstorm Sandy. In 2015, he slept three nights on the slate outside of the Municipal Services Building beside an artist’s labyrinth.

Today, beside the windows of the TD Bank, Ta’Bon spreads a fifteen-foot bolt of canvas. On its upper half, he has drawn a perfect likeness of Martin Luther King Jr.’s features: the gentle nose, dark eyes, mouth parted in speech. The lines are assured. The shading committed. The rest of King remains in faint lines. Ta’Bon weighs the corners of the canvas down with rolls of duct tape and an empty 5-gallon water jug for donations.

The stream of commuters and shoppers is steady, and exactly zero drawing gets done. People stop, arrested by the sight of a man in a jail suit and his portrait of King.

“It’s a cape,” he explains. “I’m going to attach it to other sections that are finished,” he says. “Then, I run.”

Ta’Bon, strapping a yoke around his shoulders, plans to jog with the cape—with a projected length of 70 feet—around the city. “Seventy miles in seven days with 70 feet,” he says. “It’ll be a record. Somebody tell Guinness. Longer than Batman, Superman and Liberace put together!”

Over the next two hours, Ta’Bon engages with a few dozen people, two or three at a time. When he speaks, it’s intense. He relives stories in the telling, acting out parts and revealing his life. His metaphors rove anywhere from the Jonah and the fish to the iPhone 7. He kneels over his portrait of King, saying “Here’s a man who got his throat shot out the back of his neck, for what? For love!”

And when Ta’Bon listens, all channels are open. He meets your eyes, nods, and greets your truth. It’s on you to match his honesty. This is Ta’Bon’s gift. He’s an injured man with strength, a man in chains who is radically free, and his presence challenges you to be better.

The sun casts William Penn on the clock tower in a golden dusk light. Everywhere else is cold. Ta’Bon rolls up his bolt of canvas and shakes his donation jug. “We did pretty good,” he says. He’ll need a good deal more to weatherproof the Un-Prison Cell and to get a new radiator and waterpump for the secondhand U-haul he’ll use to tow the cell around the city, which is to say nothing of the money he’ll need to keep himself and those depending on him alive. “I feel my chin dropping sometimes,” he admits, but then, catching himself in pity, he laughs: “Da-da-da-daaa! The real-life superhero: OG Law Law!”

And there’s more to look forward to: the release of the documentary, and an acting turn in a narrative film by Philadelphia’s own Neighborhood Film Company.

As I drive Ta’Bon back up Broad to Germantown Ave. I ask him about the 70-mile, 7-day run. “I’ll do Broad Street top to bottom. Market top to bottom. Lancaster, Kensington.” It’ll be his third year.

“Doesn’t it hurt?” I ask. “It’s gotta be heavy.”

He shouts: “It’s like three-pounds of drag! And that canvas sticks to the ice like tape! Yes, it hurts, but if you just put one foot in front of the other and stay focused on your destination, nobody can stop you. It’s an inspiration every time I finish.”

I tell him that he’s free in a way I am not. Running the streets with chains, a banner and prison-coveralls? I’d be afraid to come off insane.

“I was a little self-conscious as first, but in jail you develop an I don’t give a fuck switch,” he says. “It comes from getting strip-searched in front of other men.”

Ta’Bon doesn’t see himself having much of a choice. This is a mission: “It’s not for me to turn my back,” he says.

And he believes it works. “It’s crime prevention,” he tells me. “You’ll be on your way to do something dirty. You’ll see that jail suit coming. Hear those chains. You’re gonna examine where you’re at.”

What’s more, it’s beautiful. The cape’s longest section bearing his mantra Fight Hate with Love is full of the signatures and hopes that he’s collected from people on his routes. As he runs, the drag lightens, and soon he’s off, carrying these prayers through the city.

RELATED STORIES FROM THE CITIZEN

- On the heels of the release of Concrete Cowboy on Netflix, Neighborhood Film Company’s Ricky Staub and OG Law check in about telling an authentic Black story, saving Philly’s urban riders—and having Idris Elba on your side

- With the hit documentary The Social Dilemma and her latest children’s book, author, filmmaker and philanthropist Hallee Adelman continues to empower young people

- As its commercial business has exploded, Neighborhood Film Co has taken time out for a short paean to the place Ricky Staub loves most in the world: North Philly

- Ricky Staub was on his way to becoming a Hollywood giant. So why is he in Brewerytown mentoring the recently incarcerated?

- Local film experts share 30+ of their favorite flicks to stream during the pandemic