Like many American cities, Philadelphia is built on land that wants to be wet. Franklin Delano Roosevelt Park (FDR) sits in a particularly soggy, southern corner, right at the junction where the Schuylkill River rushes into the Delaware. The park is perforated by several lakes and water channels and flooding regularly renders pedestrian walkways impassable. Over the decades a monstrous tonnage of earth has been trucked in to raise the level of the park. It has been hauled in from the excavation of subway lines, the construction of railway lines, and the demolition of water sanitation plants.

FDR is estuarial bogland posing as parkland, a place where the city and swamp collide and form startling juxtapositions. The Tastykake headquarters, for example, can be smelled in the southwest corner of the park where the scents of Butterscotch Krimpets mix with pine sap and you can see the bright, blue steel of the Girard Point Bridge jutting out of the tree line into the sky.

Cheryl Brubaker is the tenant and custodian of Bellaire Manor, an 18th-century house built at the entrance to FDR’s old golf course. Brubaker moved in, in 1986 and has seen increasing puddling around the course. “They put like 30 feet of fill in here when they built the course (1940) … but of course, that has not been replaced … so it’s just slowly sinking and settling … In 2018 one of the guys told me that they had closed the course 80 days out of the season because of flooding.” Eighty days is one-third of the golf season.

Something gloriously shambolic and uncontrollable is happening at the Meadows.

The 146-acre course officially closed in October 2019, shortly after the release of a Master Plan designed to transform the entirety of the park. The plan came in the form of a lengthy document full of utopian renderings of soaring kites, beatific children, and lovers strolling at the golden hour. Phase one of the plan was supposed to kick off in 2020, but there was, of course, a hitch—a pandemic-sized hitch—and all the funds necessary to implement the plan were diverted.

Not a shovel was raised. Not a stake was driven. After 80 years, the seeds beneath the golf course which had been invisibly waiting for the mower to cease its rounds, began to germinate.

Along the fairways and through the putting greens, speedwell, celandine, and chickweed erupted. Goldenrod and boneset followed, growing in dense stands taller than the humans who once golfed there. Roaring dandelions and swamp rose-mallow punctuated the green as magenta-stemmed pokeweed tangled with blackberry canes. Foot-high oak saplings and bald cypress babies began to circle their mother trees. Seed heads exploded, monarch butterflies alighted like glowing embers upon the milkweed, praying mantises stalked the rushes, crickets sang to the very bitter end of autumn, and goldfinches bobbed their lucent trails across the thorny crowns of nursing thistle heads. Someone sighted a snapping turtle, then an otter.

In 2020, the birds and bugs were all thriving at the Meadows, but what about the humans? The humans were not yet vaccinated and desperately seeking ways to safely congregate or to escape the doom of Zoom. As people started wandering into this newly resurrected meadow, there was an uncanny synergy of desires, as if the Meadows had risen up to embrace its new visitors, to offer them resilience in the face of an escalating death toll—bloom in a moment of terror and quarantine.

South Philly resident Christina Zani says that the first time she entered the Meadows she felt like she was in Tuscany. “The rolling hills and the grasses and the sort of groomed wildness of it was so breathtaking. We brought both kids and the dog, and everyone was just sort of tumbling and rambling and like arms stretched out and just feeling curious and free and running in the sun. It was a sanity saver.”

Preserving the Meadows, unfortunately, was never part of the Master Plan

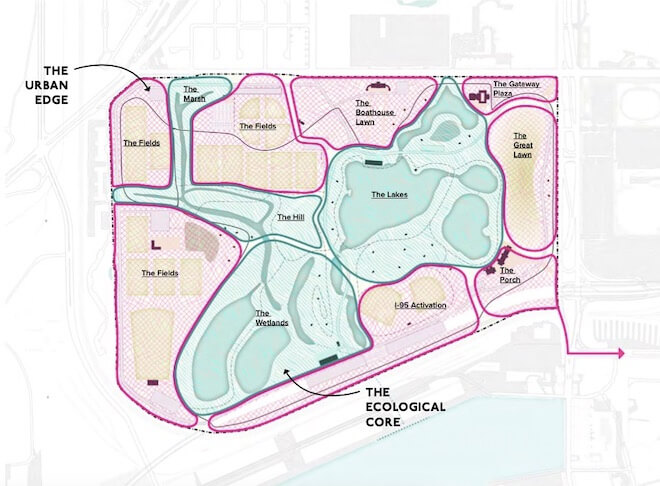

The Master Plan calls for 12 multi-purpose athletic fields, 10 tennis courts, five parking lots, four baseball diamonds, four basketball courts, a playground, a concession stand, and one driving range.

To be sure, the Master Plan has admirable dimensions. This is not a story of goodies vs baddies. This is a story of a well-vetted plan, a plan that went through rigorous community outreach, a plan that was called into question not by feuding parties or political scandal, but by the sheer beauty and resilience of a wild meadow.

The plan will restore over 30 acres of wetlands, develop a welcome center (with bathrooms!), fix the tidal gate, which the plan explains “effectively allows the park to exist,” and attempt to rejigger the park’s entire topography so that it won’t completely disappear under rising tides in the next century. It will build several large lagoons and use the excavated fill to once again raise the level of the marsh. Construction crews will essentially sculpt a new park, much the way a sandcastle is built—scooping out lagoons instead of moats to be heaped into hills instead of towers. Unfortunately, we know what eventually happens to sandcastles. Nevertheless, “FDR Park has always been a product of human invention and imagination and it will continue to be in this resilient vision for the historic park.”

“A product of human invention and imagination,” reveals an interesting point of view. The park has unarguably been sculpted by humans, but this phrase bends toward a domination-narrative that has proven to be a failing narrative in the past. In the wonderfully wry words of Elizabeth Kolbert, “If control is the problem, then, by logic of the Anthropocene, still more control must be the solution.”

In contrast, something gloriously shambolic and uncontrollable is happening at the Meadows. Cheryl Brubaker tells me she watches people pause at the threshold—wondering not only what path to take, but how a golf course disappears beneath six feet of flowers. The resiliency of the seed bank literally startles people—all that latent wild power resurrecting itself after 80 years of dormancy. No one even tilled the soil.

The Meadows is “a place I can breathe again,” says Dominique Messihi, who co-runs a homeschooling pod there. Perhaps this encounter with wildness is so refreshing because we live in an age where we, for the most part, shape the earth processes that once shaped us. Before us, only a legion of volcanos or an asteroid colliding with the earth could cause a great extinction event. Now we are the asteroids. In the Meadows, many of us feel, at last, this relinquishing of control, this psychic break, this abnegation of a colonizing will. Perhaps we feel the absence of—for lack of a better phrase—a master plan.

The architects and defenders of the Master Plan point out that the Meadows is nice, for now, but it is temporary, full of invasives, and not even a real meadow but an artificial one. When asked in a public forum whether or not the Meadows would be preserved, Maura McCarthy, Executive Director of Fairmount Conservancy, replied—“This is not a place a meadow would exist in nature if we hadn’t artificially created it. It’s at the bottom of the bathtub, that’s actually below sea level … Where we can, yes, we will artificially recreate some of the landscape of meadow.”

Field scarcity seems like a communication and distribution problem, not a land use and construction one. We have several recreational sports fields in South Philly. What we don’t have is wild space.

If the forum had been a live discussion, not a webinar, I could have interrupted to clarify that it is not the habitat category of meadow that moves me—it is land engaged in self-directed creation; it is a realization on witnessing such numinous creativity, that the land is not an object, but a subject, not an it, but a thou.

If FDR is at the bottom of the bathtub, wouldn’t it be better to keep it a meadow/emerging marsh than turn it into a multipurpose recreational zone thousands of people depend upon for dry turf? According to the Master Plan, “Climate projections estimate Philadelphia could see an increase in average annual precipitation of up to five inches, and sea level of up to four feet by 2100.”

These are, of course, shifting predictions that grow wetter and deeper as our emissions rise. If the climate warms by two degrees Celsius, a map on climatecentral.org shows tides will surge as far as Oregon Avenue, one mile north of FDR Park. The acreage where the Meadows now sits has failed as an athletic zone in the past under less pressure. In the face of catastrophic climate change, why try again? Let the space be muddy and let it be wild. A green sponge is always the best buffer against rising tides.

What else could we do to save the Meadows?

Instead, we could use the $98 million allotted for field construction at FDR to build athletic zones in neighborhoods on higher ground closer to residents. As one working parent commented in a virtual FDR open house, “I don’t need fields at the farthest southern point in Philly. There is a soccer field that is currently permanently locked two blocks away from my house. Sports fields and playgrounds belong in neighborhoods unlocked and maintained.”

The soccer field she’s talking about turns out to be the one across the street from me—Columbus Square. It’s a balmy Sunday, for February, and the field is locked right now. I see two teenagers trying to scale the fence. As I watch them struggle to break in, I wonder if this feeling of field scarcity is really an administrative failure. I go online to the Parks & Rec finder and search for “soccer.” It comes up with eight hits, all of which point to activities, not locations, and for some reason includes a Gamblers Anonymous meeting. How exactly do you find a vacant field in this city?

I ask Alvaro Drake-Cortes, a liaison between FDR and the soccer leagues who often use its fields. Drake-Cortes tells me that the two existing fields at FDR aren’t in great shape, and the players could use a few more. But when I ask for the right amount of fields, he says, “Twelve may be a little bit much, just to be honest with you.” But even if 12 were the right number, 12 fields should and could be found (or built) within the city proper without fragmenting the vital space emerging at South Philly Meadows.

As people started wandering into this newly resurrected meadow, there was an uncanny synergy of desires, as if the Meadows had risen up to embrace its new visitors, to offer them resilience in the face of an escalating death toll—bloom in a moment of terror and quarantine.

And before we spend $100 million on the construction of new fields, could we spend a few thousand to develop a citizen-friendly website where existing public fields are listed, mapped, and reserved? As I look out my window at the empty goals across the street, field scarcity seems like a communication and distribution problem, not a land use and construction one. We have several recreational sports fields in South Philly. What we don’t have is wild space.

The Master Plan is designed to take FDR from two soccer fields to 12, from zero basketball courts to eight, from one playground to two. If the plan were simply to double or even triple the amount of fields existing presently, much of the Meadows could still remain. Where does the incentive for this amount of increase come from? Revenue, perhaps? Permits will be issued for the use of fields.

It’s also well documented that Philadelphia is a candidate for the 2026 World Cup and has pitched South Philly Meadows as one of the potential spaces for their tournament. If Philly won the bid (a significant if), FIFA could contribute up to $200 million dollars to support elements of the Master Plan. A notable number, given the budget for the entire Master Plan is $256 million dollars, of which only $90 million has been currently raised. But, unlike any of the other spaces included in the FIFA pitch, FDR is cherished public land.

In June 2021, a petition against the Meadows’ inclusion in the FIFA bid started circulating. I signed it along with about 2,000 others. Eventually, I received an email in my inbox saying there was a protest scheduled for September 22, 2021, the day of FIFA’s site visit.

On the first day of fall, a crisp breeze cut through the lingering summer haze. A biker ahead of me had strapped a cardboard sign to his rack that read, “I love soccer, but save the Meadows,” next to a carefully drawn monarch sipping up the nectar of a pink milkweed flower. At the Meadows’ entrance, other protestors carried banners that read, “Meadows not money” and “Preserve our wild space.”

But even if FIFA doesn’t pave the way for the destruction of the Meadows, the Master Plan will still attempt to cover the majority of it in a layer of synthetic turf. Synthetic turf is convenient: It doesn’t need to be mowed, fertilized or watered and won’t turn into a mud pit. But it also doesn’t support the larger ecosystem or sequester carbon in an age when carbon emissions are racing towards a tipping point. Synthetic turf is derived from fossil fuels, and so creates a significant amount of emissions before it has even been rolled out.

Twelve athletic fields worth of synthetic turf is the equivalent of every registered citizen in Philadelphia dumping 130 plastic bags on the Meadows. A pointed comparison, considering the fact that the city recently enacted a ban on plastic bags. The fake turf will inevitably break down, introduce microplastics into the watershed, be ingested by wildlife, and pollute those wetlands the plan purports to revitalize and bolster. Fake turf retains heat, in some cases becoming too hot to walk on. Most concerning, many synthetic turfs off-gas toxic fumes, such as styrene and butadiene, which damage the nervous system and cause cancer.

The Master Plan claims that synthetic surfaces will “maximize playtime and reduce maintenance needs,” but any surface that doesn’t degrade and regenerate itself needs to be cleaned, which can mean brushing, hosing down and sometimes vacuuming. In as little as 10 years the fake lawn could need to be replaced. How much will that cost? The Master Plan says it will increase the meadow habitat at FDR by 10.8 acres from zero acres. This is plainly incorrect. It should be amended to state that the Master Plan will bury almost 30 acres of currently existing meadows beneath a layer of plastic. Where is the “resilient vision” there?

A meadow is an interconnected web

The monarch beats its wings to the rhythm of the entire carnival of creatures that has summoned it into being. Our ecosystems are already so fragile. If the meadows are divided—like so many cut-up squares of carpet—they will be subject to all the consequential unraveling.

Curious about some of the species that have appeared in FDR since the Meadows return, I set out on a long walk with Holger Pflicke, an avid birder who has been stalking the area with his binoculars since before the golf course closed in 2019. “The good thing about Philly birding,” he says, “is there is always a hole in the fence somewhere.” He is one of the many community members who consulted on the design of the Master Plan, but now wishes that the Meadows could remain. Even in the midst of January, suited up in our mittens and hats, we find the place bustling with white-throated sparrows and mewing woodpeckers.

Since the rebirth of the Meadows, Pflicke has begun spotting birds he’s never seen in FDR before: clay-colored sparrows, vesper sparrows, dickcissels, blue grosbeaks, and eastern meadowlarks. “All that growth that came back led to something,” he tells me. People will talk about invasives here, he says, but even if phragmites or mugwort are not ideal habitats “they still provide some habitat.” If you’ve ever noticed the red-winged blackbirds chortling in the phrag, you can attest to this. Today, Pflicke is hoping we can see an orange-crowned warbler.

If you ask Pflicke what drives him to wake up at dawn to survey the Meadows before work, he’ll tell you about the miracle of migration—wild geese and blackpoll warblers starting in Canada and flying nonstop all the way to South America. Birds have always been a symbol of resilience and also a puzzle piece with planetary dimensions. We may witness them for only a moment, but through these brief intimacies, we are stitched into the pattern of the seasons and become attuned to the tilting gyre of the giant planet to which we both belong.

Suddenly, Pflicke spots the orange-crowned warbler. He’s there in the shrubbery straight ahead, a greenish-yellow feathered-plumpness with a gray hood. A second arrives. Two in the same view!

“And that is only due to the Meadows,” says Pflicke with joyful pride in his voice. “And that is awesome.”

We are just beginning to discover what the Meadows is —just starting to imagine how it can intersect with our lives. The Meadows is not just a space where birds and bugs are nourished; it nourishes us all. If the Master Plan refuses to be amended, if the inertia is just too great, and the frozen in time community of 2019 is the only community whose input matters, then perhaps all that we will ever be able to say is this: for a moment we were awestruck, and felt our place on Earth.

But I, for one, am not ready to give up or to say goodbye. Are you?

Anisa George is a Philly-based writer, director, and aspiring farmer. She focuses on the intersection of ecology, culture, and performance.

![]()

MORE PARKS AND RECREATION IN PHILADELPHIA

Header photo of a child swinging in the Meadows by Dominique Messihi