In a rare special address to City Council on March 24, Mayor Cherelle Parker laid out more of the details of her administration’s Housing Opportunities Made Easy (H.O.M.E.) plan, the largest-ever public investment in housing in Philadelphia’s history.

With a commendable emphasis on urgency and results, the Parker administration’s $2 billion plan aims to create 13,500 new homes to buy or rent, and preserve 16,500 existing homes, adding up to her campaign pledge of 30,000. The plan would accomplish this through a mix of demand-side subsidies, funding increases for home preservation initiatives, tax changes, and regulatory reforms to some of the city’s byzantine land use laws and processes.

There are lots of details still to digest from the Mayor’s address and accompanying plan document, and more specifics should solidify as the administration continues negotiating with City Council and housing stakeholders. Already though, a few pro-supply concepts mentioned stand out as more likely to get the job done to create the 13,500 new units Mayor Parker has called for.

What should be on the pro-supply policy menu?

The biggest obstacles to new home building in 2025 have to do with financing projects, the rising cost of materials and other inputs, and restrictive land use policies that cause costly delays and limit the revenue potential of a piece of land.

Our city government doesn’t control interest rates, and it also doesn’t control the cost of materials, which are all likely to get even more expensive with President Trump’s tariff increases on lumber and metals and other standard building materials. But our city government has a lot of control over its land use laws and policies, and they could also make some useful interventions in the housing finance space. The outsized municipal control over these areas makes them some of the most important points of emphasis as the negotiations proceed.

In her address, Mayor Parker acknowledged the contribution of restrictive zoning and historic preservation to the city’s housing affordability challenges, and said she asked 25 city departments to make recommendations to “streamline processes, cut red tape, and make regulatory and legislative changes that will facilitate the faster production and restoration of housing — without sacrificing health and safety.”

Parker didn’t offer many specifics about this except to say that “early priorities under this plan include cleaning up the code, addressing zoning inconsistencies to reduce the need for exemptions, and expanding development opportunities in transit-oriented overlays.”

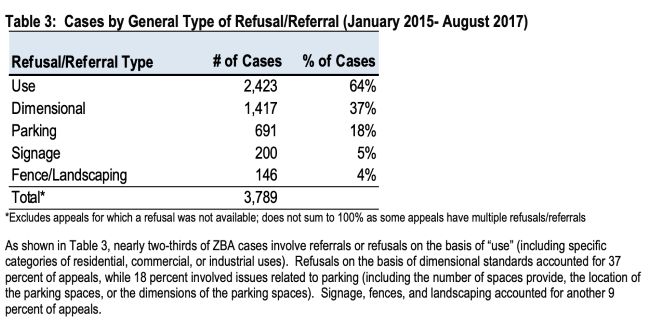

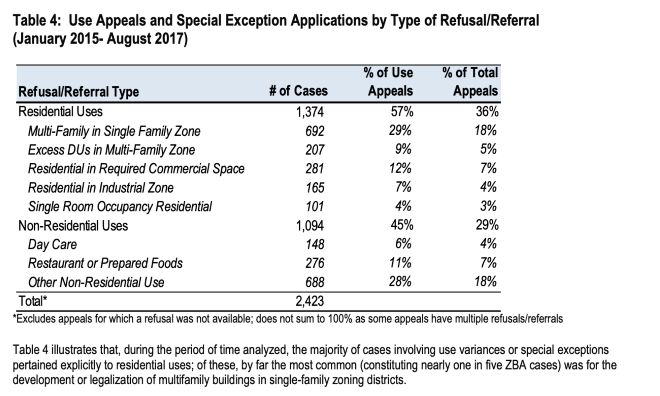

A good place to start in working out the specifics for a zoning reform agenda would be to look at the last few years’ worth of Zoning Board of Adjustment (ZBA) cases, and analyze the most common reasons why builders pursue zoning variances — the exemptions Parker mentioned. In other words, what are the building types that people want to build that aren’t currently allowed under the regular code? Is there actually a good reason why they aren’t allowed, or is it a sign of a bad law that should be changed?

The Planning Commission released exactly this kind of analysis in 2019, reporting on the first five years of data following the Zoning Code Commission’s 2012 code overhaul package. There hasn’t been another publicly available analysis since then, but with housing red tape in the Mayor’s crosshairs, the time is ripe for an updated analysis through the present day.

That report found that some of the more common types of variance requests involved people trying to build or legalize existing multifamily housing on lots zoned for single family housing, excess multifamily dwellings in a multifamily project, and of course, parking. Parking alone accounted for around 18 percent of zoning refusals during the period studied.

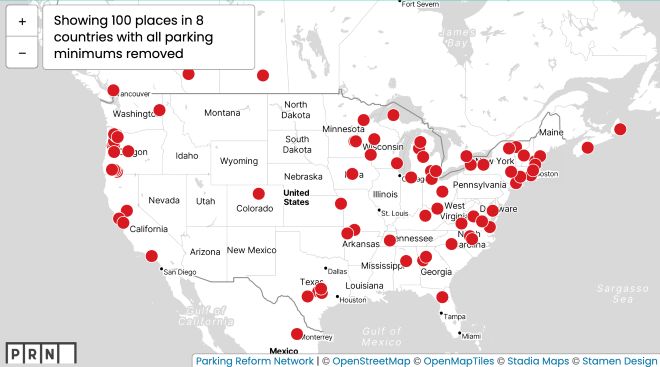

Better understanding what types of buildings people want to build, and then rewriting the code language to broadly legalize those building types would go a long way toward slashing the ZBA’s caseload. The administration should follow the data in setting priorities, but it’s also easy to see from the 2019 analysis how allowing more small lot multifamily housing like duplexes and triplexes, or eliminating parking mandates — both standard fare by now in other cities pursuing pro-housing reforms — could radically reduce the logjam at the ZBA while allowing badly-needed housing to get faster and more predictable approvals.

More housing near SEPTA

Mayor Parker’s goal of 13,500 new housing units is ambitious, and can’t be achieved exclusively with infill rowhomes on city lots, even under a best-case scenario for programs like Turn the Key. More large and medium-sized apartment buildings will also be necessary to achieve that kind of volume — but the political sticking point is always about where to permit them. These are the kinds of high-profile projects some residents love to fight whenever they’re given the opportunity, which is precisely why more action is needed to place them in the by-right approval basket in more cases.

A further economic constraint is that there are only so many places in the city where high-rise construction makes financial sense from a builder’s standpoint. Transit station areas are a great option for high-rise buildings from a planning standpoint, because many have high enough land values to support high-rise or mid-rise construction thanks to their proximity to useful public transit infrastructure. And the “Not in My Back Yard” resistance politics are somewhat more muted and manageable since most land in the city is not located within a 10-minute walk of rail transit, leaving most homeowners unaffected. Anecdotally, from my time being involved with my neighborhood association, I’ve also seen meeting attendees take a much more forgiving attitude toward higher-density housing when it’s close to the L than when it’s in the middle of a block of rowhomes.

Mayor Parker’s vision for housing in Philadelphia is as bold as the moment requires, and as she emphasized in her address, the city is starting from a position of strength.

Meanwhile, SEPTA is staring down the barrel of another financial crisis, with service cuts and fare hikes already guaranteed even if Governor Josh Shapiro’s funding proposal is enacted exactly as proposed. SEPTA desperately needs more ridership and more unrestricted local revenue from the farebox, and high-density station-area land use conditions are among the most important factors determining transit ridership.

A recent paper from the Niskanen Center, “Philadelphia Regional Rail: Population Density and SEPTA’s Fiscal Crisis,” looked at population density in the neighborhoods surrounding SEPTA’s Chestnut Hill East and West regional rail stations and found that they averaged around 7,800 people per square mile — substantially short of the 10,000 people per square mile threshold experts say is needed to support rail service. If the city could manage to bring the neighborhoods around Chestnut Hill East and West up to the same average population density as the rest of the regional rail-served neighborhoods through more housing construction — about a 35 percent population increase — that would put those lines in the top three for fare recovery system-wide.

Philly’s existing Transit-Oriented Development law is not particularly strong and needs some serious retooling to be effective, both for the sake of Mayor Parker’s housing goals and also as part of a strategy for SEPTA’s fiscal and ridership recoveries. Reforming that law is about as close to a free lunch as the city can get, both for housing production and transit stabilization.

Untangling city land

One of the more interesting moments in Mayor Parker’s address to Council came when she proposed a new framework for approving housing on city-owned land. Acknowledging “the elephant in the room” of councilmanic prerogative, Parker proposed changing the way city land sales are approved. Rather than a City Council resolution for each individual property, Parker called on City Council to work with her administration to pre-authorize all city real estate for housing, or at least 1,000 of the roughly 4,000 city lots to start.

This solution would be a novel approach to the problem I wrote about here previously, where the Original Sin of Land Bank dysfunction is the state law requiring a vote of the municipal legislature to sell city-owned real estate. In Philadelphia, the approach to-date has been to require a Council resolution for each individual property, but it would also be perfectly acceptable within the law to vote on the disposition of a whole bundle of city properties all at once, as Mayor Parker is suggesting.

This would also help with the other main Land Bank problem, where Council opposition to Turn the Key and other housing proposals often comes in at the very end of the process, after the applicant and Land Bank staff have already spent a lot of time and money on pre-development costs and staff reviews. Authorizing city land for housing right from the beginning of the process would remove the uncertainty about a potential last-minute withdrawal of Council support that haunts would-be applicants and shrinks the pool of interested builders. Mayor Parker also floated the idea of creating a pre-approved list of developers for city land, probably similar to the qualification criteria for Turn the Key projects, so that the frequent flyers have an easier time going for their second or third projects.

Some Council members are already gently pushing back on this, which is how you know the Mayor is onto something that would probably work. Residents frustrated with the city’s current dysfunctional approach should pay particular attention to how this plays out.

Pre-approved land, pre-approved developers … pre-approved plans?

On the topic of the Land Bank, Mayor Parker also suggested that the Department of Planning and Development could sit down with individual District Council members to develop design guidelines for homes on city land in their districts “to ensure that construction is consistent and complimentary with the block.”

As someone who temperamentally would not really want to see city government go deeper into regulating building aesthetics, I can see the ways this could go badly wrong. Tune into any Art Commission hearing about a business sign application or a streetery if you want to sink into despair.

Acknowledging “the elephant in the room” of councilmanic prerogative, Parker proposed changing the way city land sales are approved. Some Council members are already gently pushing back on this.

But there are versions of this idea that could potentially work well, by going a little further than Mayor Parker seems to be suggesting. If we’re getting pre-approved land, and pre-approved developers, why not make the jump to pre-approved architectural plans too?

South Bend, Indiana, Bryan, Texas, and some other mid-size cities have been experimenting with “pattern zoning” where the city government keeps a catalog of pre-vetted, pre-approved home plans on file, which any builder can use, sometimes in select locations. The infill version of this idea, especially with Philadelphia’s small and differently sized lots, could have its own unique challenges, but it’s also the case that most rowhomes have a pretty standard range of layouts and have been a fairly cookie-cutter housing style ever since their inception here.

City government could play a useful role by making some better cookie cutters, so that it’s more often the case that the easiest, laziest option available is something that looks aesthetically-pleasing. Rather than layering on more restrictions, we could make it cheaper and faster to build something nice-looking. One could imagine the city hosting some kind of architectural competition for these plans, or perhaps administration staff could look back at some particularly attractive plans approved in the past, and work out some type of royalty payments for the architects involved that pay out whenever those plans are used.

Mixed-income public development

The H.O.M.E. plan proposes funding increases for a wide range of housing-related programs, most of which have to do with home repair, preservation, blight reduction, and assistance for homeowners and tenants. The city has many popular and effective programs such as Basic Systems Repair that deserve a funding increase, and this is an important piece of a strategy for housing stability, especially with some of Philadelphia’s unique characteristics.

It’s also the case that the plan so far is light on financial strategies for new housing development, and would benefit from some more thoughtful engagement from the administration and housing stakeholders as to what would be the most effective use of some portion of the $800 million in city bond revenue within this bucket.

“Let’s prove the people wrong who say we can’t work together.” — Mayor Cherelle Parker

There is a two-word reference in the plan to a “public developer” and another reference to gap funding for Low-Income Housing Tax Credit projects through the city’s Affordable Housing Preservation and Production Fund. What is meant by “public developer” is so far undefined, but this term has sometimes been associated with the work of Paul E. Williams and the Center for Public Enterprise, who have helped several cities and states create revolving construction loan funds for mixed-income development.

The linked paper describes an example from Montgomery County, Maryland’s Housing Opportunity Commission, where the HOC was able to rescue an already permitted market-rate project that was struggling to get private financing, by using revolving loan fund dollars and taking a majority-ownership stake in the property, while securing 30 percent of the units for permanently-affordable rentals at 50 to 70 percent AMI.

Atlanta and Chicago have similar revolving construction loan funds, and it’s worth exploring in Philadelphia, where allegedly as many as 9,000 already approved housing units are stranded for lack of affordable financing at the moment, according to industry sources.

Especially if combined with Rep. Jared Solomon’s affordable housing tax abatement — approved by Harrisburg, not yet adopted by City Council — and PHA’s strategy of buying up market-rate apartment buildings for Section 8 rentals, Philadelphia could have something approaching a self-sustaining system for increasing the supply of permanently-affordable rental housing with a one-time investment of between $50 to $100 million from the bond proceeds or other sources. Importantly, this would be a complement, not a competitor, with existing federally-funded affordable housing production initiatives, and it also wouldn’t come with any of the regulatory strictures or time costs associated with federal Low-Income Housing Tax Credits.

Mayor Parker’s vision for housing in Philadelphia is as bold as the moment requires, and as she emphasized in her address, the city is starting from a position of strength with an existing roster of effective, proven strategies that could benefit from more resources and more user-friendly processes. Whether her production goals will be successful depends substantially on whether City Council will cooperate in making certain processes faster and more predictable, sometimes reversing past choices to make things slower and more discretionary.

As Mayor Parker put it in challenging her colleagues to work with her on the Land Bank, “Let’s prove the people wrong who say we can’t work together.” Here’s hoping they do.

Jon Geeting is the director of engagement at Philadelphia 3.0, a political action committee that supports efforts to reform and modernize City Hall.

![]() MORE ON HOUSING SOLUTIONS FROM THE CITIZEN

MORE ON HOUSING SOLUTIONS FROM THE CITIZEN