This summer, we commemorated the 50th anniversary of the moon landing, Neil Armstrong’s “giant leap for mankind.” The feat was a modern wonder of human ingenuity, and it captured the imagination of an entire planet. Only a cynic would regard the Apollo 11 mission as anything other than an apotheosis of American courage, intellect, vision and salutary patriotism.

What a difference a half century can make. In a country purported to be reclaiming its greatness, our current and would-be leaders seem to take an awfully small view of America’s potential.

Prefer the audio version of this story? Listen to this article in CitizenCast below:

Despite the mountainous majesty of President Trump’s ego, his skin is paper thin and his political imagination is puddle deep. Between Twitter tantrums and grotesque thumbs-up photo ops with orphaned mass shooting survivors, Trump’s conception of grandness extends only as far as the size of his rallies. Otherwise, he insists, America is full. It is a claim used to back his cruelly xenophobic and white supremacist policies. And it is, of course, wrong.

In a country purported to be reclaiming its greatness, our current and would-be leaders seem to take an awfully small view of America’s potential.

In fact, America is facing a dangerous decline in its productive population, with more than 80 counties, comprising an aggregate population of 149 million, seeing a drop in their number of working-age adults over the past two years. This is bad news for all manner of business, and not just the poultry processing plants of the sort that exploit immigrant workers who face increasingly ruthless persecution by the President’s immigration authorities.

Trump’s brazen undermining of national prosperity in service of a myopically bigoted agenda is the manifestation of what his opponents find so repellent about him; his venality, narcissism and nihilistic pettiness. But for all the boorishness that so outrages his electoral opponents, their responses are discouragingly bereft of a positive vision in their own right.

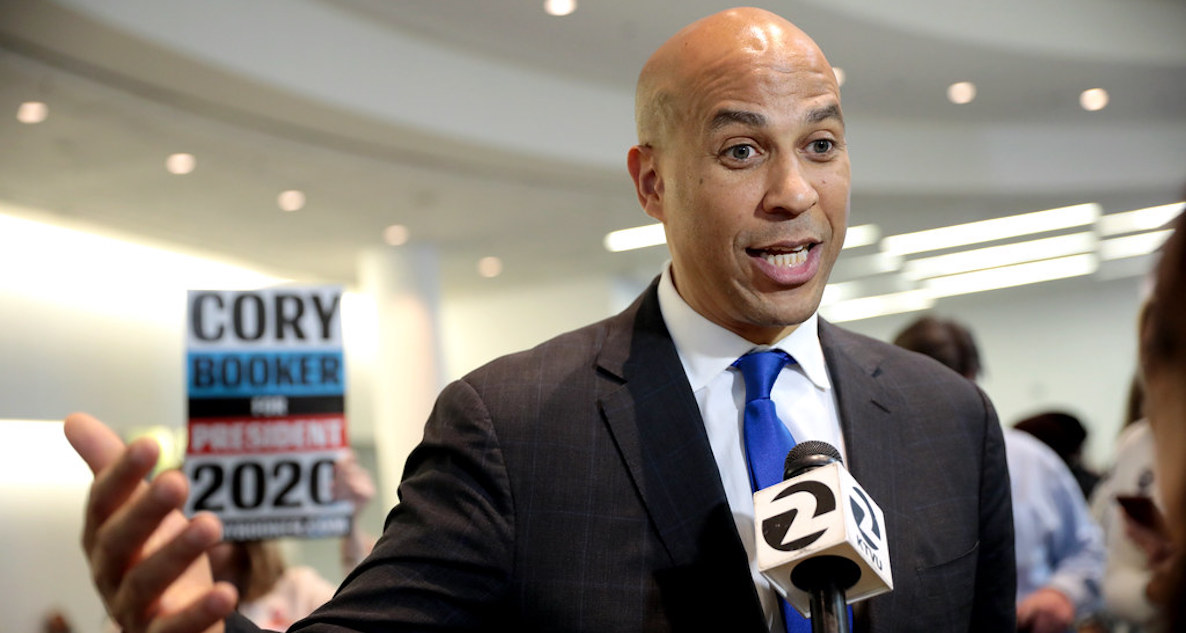

The recent two-night broadcast of the preposterously overstuffed Democratic presidential debates cast a light on just how compromised, complacent and uncompelling most of these candidates (not to mention our dog and pony show campaign process) are. A stage full of indistinguishable stuffed shirts eked in a few unremarkable bromides here and there, without managing to be the least bit inspiring or even memorable.

That is, until Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren confronted the former Maryland congressman John Delaney. After Delaney repeatedly dismissed Warren’s support for broader social safety net policies like Medicare for All as “more free stuff” and “impossible promises,” Warren shot back, “I don’t understand why anybody goes to all the trouble of running for president of the United States just to talk about what we really can’t do and shouldn’t fight for.”

It’s safe to assume that Warren does, in fact, know why someone would go to all the trouble, if that someone is John Delaney, worth $92 million from his stint as a health care financier. The medical industrial complex needs their guy in the arena too. Still, it shouldn’t come as any surprise that Warren’s riposte got the biggest applause of the night. She tapped a vein of popular frustration at the notion that big ideas are necessarily bad ideas, that dramatic policies to improve the lives of ordinary Americans are inherently unworthy of the risk.

For a generation now, middle and working class folks have been stifled under the message that their lives don’t merit an investment in big ideas and dramatic policies. The austerity program imposed by the Reagan administration sounded the death knell of New Deal liberalism, and Bill Clinton’s declaration that “the era of big government is over,” was the bipartisan hammer driving the nail into its coffin.

![]() Most Americans today have spent the majority of their lives being told that government is incompetent, untrustworthy and an impediment to “freedom.” Meanwhile, the corporate powers that benefit from popular antipathy toward the public sector have realized success beyond their wildest dreams making government at once their tool and their whipping boy.

Most Americans today have spent the majority of their lives being told that government is incompetent, untrustworthy and an impediment to “freedom.” Meanwhile, the corporate powers that benefit from popular antipathy toward the public sector have realized success beyond their wildest dreams making government at once their tool and their whipping boy.

It’s a dispiriting state of affairs, but in some dimly lit corner of our collective unconscious marked “History,” we know we’ve been here before. In the years preceding the Great Depression, the watershed crisis of the 20th century, the tycoons and robber barons of the day had seized the levers of federal power, turning the American economy into their private playground and piggy bank.

When the recklessness of the oligarchy came home to roost, tens of millions of blameless Americans were plunged into misery, while tens of millions more languished at the brink. As the social fabric of the nation began to rend apart, the fissures began to arise various factions that would strike familiar chords today. On one hand, there were the nativists, the Jim Crow racists, the openly fascist gangs preying upon the most vulnerable of their neighbors, and of course, the financial and industrial capitalists themselves, content to see an aggrieved working class divided against itself rather than united against the actual perpetrators of their exploitation and suffering.

Our nation was at the precipice of collapse, and were it not for the election of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, a man who understood that the idea of the nation was about more than lining the pockets of a tiny coterie of bankers, steel magnates and railroad tycoons, it is easy to picture America tumbling finally into oblivion.

FDR is of course most well-known for his immortal admonition, “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself,” from his first inaugural address, but in fact, he delivered his strongest articulation of his vision for an America truly of, for and by the people four years later in Philadelphia.

![]()

It was in the summer of 1936 at the University of Pennsylvania’s Franklin Field that FDR gave his “Rendezvous with Destiny” speech, in which he defended, justified, and placed in the context of a populist patriotism the radical overhaul of the federal government he’d undertaken in his first term. In the preceding three years, FDR’s administration had overseen the successful passage of the Social Security Act, the introduction of the Works Progress Administration which created thousands of federally funded jobs for engineers, artists, teachers and park rangers (to name but a few examples), codified meaningful labor rights for workers, and raised the marginal income tax rate to 75 percent on the wealthiest earners.

In his speech, FDR condemned the tyranny of America’s 20th century “economic royalists” who built “new kingdoms upon concentration of control over material things.” And he made his prescription plain: “Against economic tyranny such as this, the American citizen could appeal only to the organized power of government.” This appeal, declared Roosevelt, was necessary to wage and win a war that was “not alone a war against want and destitution and economic demoralization. It is more than that; it is a war for the survival of democracy. We are fighting to save a great and precious form of government for ourselves and for the world.”

For a generation now, middle and working class folks have been stifled under the message that their lives don’t merit an investment in big ideas and dramatic policies.

FDR’s argument that government could in fact be a force for human flourishing, a champion of freedom, and a bulwark against the tyranny of the few over the many won the day, and it largely guided both policy and popular political attitudes for the next thirty years. Roosevelt’s New Deal liberalism informed not only the robust social welfare state he built, but the sense of shared purpose and sacrifice that sustained the American effort at home and abroad into World War II. Outlasting both Roosevelt’s presidency and his life, this political consensus made possible subsequent major social reforms, chief among which were the Civil Rights Acts of the 1960’s, Medicare and Medicaid, and various anti-poverty programs, all part of Lyndon Johnson’s “Great Society” rebrand of the New Deal.

What’s more, it’s no stretch to say that the Apollo missions culminating in the historic lunar landing in 1969 were fueled by the New Deal political philosophy. In what other collective frame of mind could the American body politic have supported a government-funded endeavor so costly, ambitious, grandiose, and perhaps most crucially, not motivated by a thirst for private profit?

Lest anyone argue otherwise, the big government policies of the 1930s through 1960s were the single most essential catalyst, engine and safeguard of America’s hallowed and now-vanishing middle class. (We need only glance at the systematic dismantling of those policies to understand the cause of its destruction.) None of this is to suggest that FDR, JFK, LBJ (and yes, even RMN) were pure bastions of wisdom and good conscience. Roosevelt’s progressive labor policies excluded domestic and agricultural workers (groups that tended to consist largely of black and brown Americans), and his legacy will be forever marred by his immoral internment of Japanese Americans during WWII. JFK was lukewarm on civil rights, and even as LBJ came to champion the biggest civil rights legislation since Reconstruction, he continued to prosecute a doomed, pointless and unfathomably murderous war in Southeast Asia.

Highlighting the shortcomings of the New Deal presidents isn’t meant to undermine the magnitude of the governmental intercession into American social and economic life during their administrations, but to dispel any idea that these men were wholly benevolent, fully enlightened sages. If anything, their great talent was the combined ability to recognize the political tectonic shifts taking place before them and the belief that America could become and remain vital only when it sought to serve a greater, collective good.

![]() FDR was certainly no labor radical or socialist himself; rather, it was the emboldened trade unionists, Socialist and even Communist partisans in America who were the foundational architects of New Deal labor policies. They made Roosevelt understand that, without workers, there would be no industry, no economy to save.

FDR was certainly no labor radical or socialist himself; rather, it was the emboldened trade unionists, Socialist and even Communist partisans in America who were the foundational architects of New Deal labor policies. They made Roosevelt understand that, without workers, there would be no industry, no economy to save.

And LBJ, who made his political start as a vocal segregationist, was no dyed-in-the wool civil rights activist. On the contrary, he was compelled, if not won over, by the persistent efforts of MLK, Rosa Parks, and the thousands of other sung and unsung heroes of the movement who gave their time, energy, livelihoods and even lives to realize a vision of America that actually measured up to its founding principles.

Ultimately, what greatness America has ever achieved hasn’t been to the credit of a few individuals in the highest positions of political authority. It has always been the result of concerted demands and shared sacrifice of the ordinary folks—young people, immigrants, nurses, teachers, workers—whose toil built and sustains this country. And those ordinary folks, who made America and who make it great, are now fighting the battle of a lifetime. In battling for fundamental rights to education, to housing, to healthcare, to food, and to a sustainable planet, they are simply demanding the critical material conditions necessary to their, and our, collective survival.

As we endure the insanity and inanity of the 2020 presidential campaign, we would do well to dismiss the various pretenders determined to tell us what we can’t do and what we shouldn’t fight for. Our next president should be one who embraces the essential truth that our only chance at claiming a meaningful, lasting American greatness depends on a vision that includes all Americans. It should be no giant leap for any worthy leader of this country to understand and accept that it’s not about them, it’s about us.

Ajay Raju, an attorney and philanthropist, is chairman of DilworthPaxson and founder/board chair of The Citizen.

Photo courtesy Bastian Greshake Tzovaras / Flickr