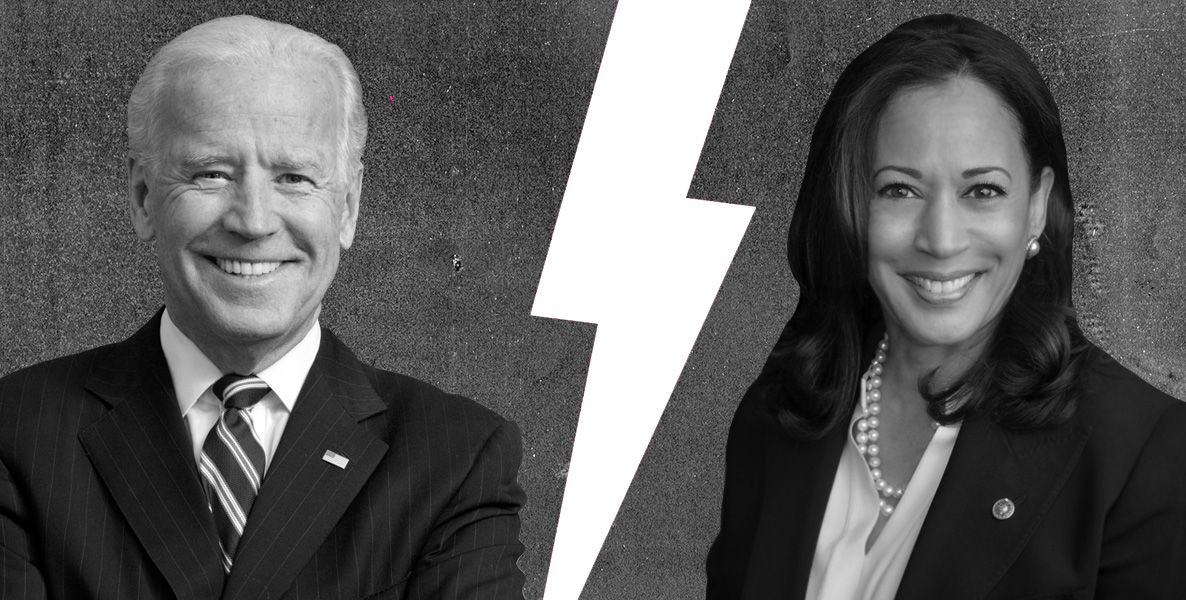

It’s probably a bad sign that, not even midway through Wednesday night’s Democratic presidential candidate debate, I started wondering when the actual debate would begin. Rather than eliciting smartly nuanced distinctions over ideas, the evening’s moderators baited the candidates with thinly-veiled invitations to rumble—“Senator Gillibrand, how do you feel about Senator Harris continuing to call her health proposal Medicare for All, when it includes a far more significant role for private insurance than the bill you co-sponsored?”—and, en masse, the candidates took that bait.

Prefer the audio version of this story? Listen to this article in CitizenCast below:

It led to the shedding of far more heat than light, which gets us to a question with grave implications: In an age where facts have been devalued and discarded, is there any mass landing strip left for substance in our public conversation?

In an age where facts have been devalued and discarded, is there any mass landing strip left for substance in our public conversation?

Let’s dive into one particular issue as a case study to get a sense of just how media and self-serving politicians conspire to obfuscate rather than enlighten: Criminal justice reform.

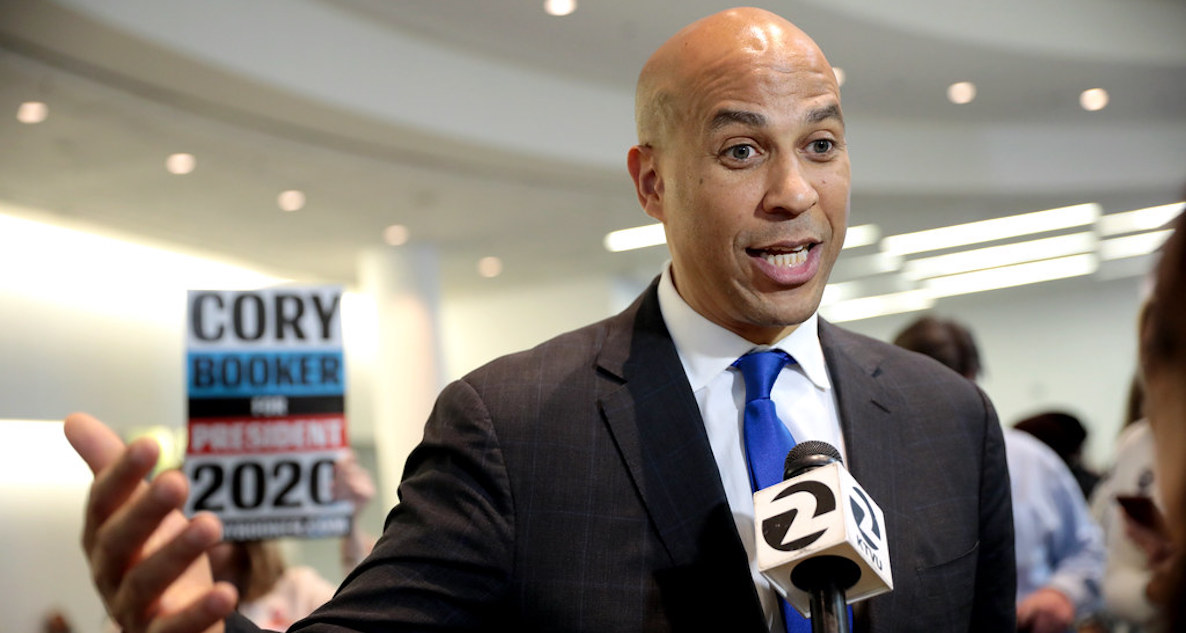

Wednesday night, as telegraphed, Senator Cory Booker attacked Vice President Joe Biden for his authorship of the 1994 Crime Bill, which is said to have fueled mass incarceration. Like Senator Kamala Harris in the previous debate, Booker came prepared with scripted lines meant to serve as lasting soundbites:

“This is one of those instances where the house was set on fire and you claimed responsibility for those laws,” Booker said. “And you can’t just now come out with a plan to put out that fire.”

When Biden responded with a script of his own—attacking Booker for stop-and-frisk policies when he was Mayor of Newark—Booker shot back with another prepackaged gem: “You’re dipping into the Kool-Aid and you don’t even know the flavor,” he said, drawing laughter and applause.

Watch the exchange in full and you notice something striking: It’s essentially fact-free, a conspiracy of actors—moderator and dueling candidates—to serve up a storyline, not to educate. This is what debate has become in our fractured politics.

It got me wondering…just what is up with that Crime Bill, anyway?

Watching the display, did you feel any smarter about the effects of 1994’s Crime Bill? Hardly. And nor did any of the talking head post-game punditry enlighten on that score. Instead, we got sports page analysis, comments about which candidate seemed “on his heels” and which had successfully “counter-attacked.” It got me wondering…just what is up with that Crime Bill, anyway?

![]()

Predictably, it’s complicated. First, was a white senator from Delaware truly behind it? Well, Biden was one of its authors, but its roots were actually owed more to the African-American Mayor of Baltimore, Kurt Schmoke, and the Congressional Black Congress, because their inner-city neighborhoods were undergoing a crime wave siege. Back then, Congressman Charlie Rangel, who represented Harlem, spoke movingly about how being able to walk safely on urban streets had become the civil rights issue of the day.

So Biden wrote, and President Bill Clinton signed, the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994. What did it do? Well, here are the facts, according to the non-partisan Brennan Center for Justice. It provided funding for 100,000 new police officers on city streets—a 28 percent increase—under the since-proven “community policing” theory that more cops engaging with citizens on city streets makes neighborhoods safer. And it provided $14 billion in grants for other forms of community-oriented engagement—the kind of programs Booker and other reformers rightly hold up as smart policy today. Among them was “Midnight Basketball,” which was much-derided by critics on the political right at the time. But the program, by providing inner-city kids with constructive late-night sports activities, was credited with lowering crime rates.

![]()

Did the Crime Bill reduce crime? Most certainly. Over the next 16 years, crime dropped 23 percent and violent crime a whopping 30 percent. Is that all due to Biden’s legislation? Of course not, but it is generally agreed that the law contributed to the historic decline.

Yet, and this is what Booker was getting at, other provisions of the law almost certainly fed mass incarceration. Incarceration had already been rising before the crime bill. From 1970 to 1994, the rate of imprisonment had blown up by 400 percent, to 387 per 100,000 people. But over the next 15 years, 1994 to 2009, imprisonment doubled.

Media outlets, candidates, activists—all are complicit in a rigged, phony debate.

According to the Brennan Center, it wasn’t the bill’s banning of semiautomatic assault weapons or its authorization of the death penalty for cop killing or even its (wrongheaded) federal “three strikes and you’re out” provision that was the primary accelerant. No, it was actually the bill’s incentivizing of states to experiment with their own tough-on-crime laws. “On their own, states passed three-strikes laws, enacted mandatory minimums, eliminated parole, and removed judicial discretion in sentencing,” the Brennan Center found. “By dangling bonus dollars, the crime bill encouraged states to remain on their tough-on-crime course.”

A discussion between smart public servants on what worked and what didn’t on a major piece of legislation like 1994’s Crime Bill would be most welcome. But instead we’ve gotten blame-shifting and one-liners, and media interlocutors more focused on manufacturing moments of conflict than enlightenment.

![]()

And now, making matters more complicated, comes a piece in City Journal entitled “Everything You Don’t Know About Mass Incarceration.” In it, author Rafael Mangual walks us through the data, and calls into question the very premise agreed to by Booker, Biden and every other candidate and talking head who engages the issue of crime and punishment: That our high incarceration rate is driven by unjust enforcement of low-level drug offenses.

“Yes, about half of federal prisoners are in on drug charges; but federal inmates constitute only 12 percent of all American prisoners—the vast majority are in state facilities,” writes Mangual. “Those incarcerated primarily for drug offenses constitute less than 15 percent of state prisoners. Four times as many state inmates are behind bars for one of five very serious crimes: murder (14.2 percent), rape or sexual assault (12.8 percent), robbery (13.1 percent), aggravated or simple assault (10.5 percent), and burglary (9.4 percent). The terms served for state prisoners incarcerated primarily on drug charges typically aren’t that long, either. One in five state drug offenders serves less than six months in prison, and nearly half (45 percent) of drug offenders serve less than one year…The claim that drug offenders are nonviolent and pose zero threat to the public if they’re put back on the street is also undermined by a striking fact: more than three-quarters of released drug offenders are rearrested for a nondrug crime. It’s worth noting that Baltimore police identified 118 homicide suspects in 2017, and 70 percent had been previously arrested on drug charges.”

Mangual makes a compelling case, but this isn’t to suggest he’s right so much as to acknowledge that whether he’s right or not isn’t even part of the conversation. Media outlets, candidates, activists—all are complicit in a rigged, phony debate.

It wasn’t always this way, folks, and you don’t even have to go all the way back to the Lincoln/Douglass debates to find examples of political discourse that more honestly fed the public good. Back during the 1992 Democratic presidential primary, national talk show host Phil Donahue literally turned his hour-long show over to the two remaining candidates for the presidential nomination: Bill Clinton and Jerry Brown.

They sat across from each other and had an hour-long conversation. They asked questions of one another, they disagreed, they made their case. It was nuanced, it was smart, it was civil. And neither of them seemed like what we saw Wednesday night: Desperate, craven, glib.

Watching it, you feel smarter for having done so, and you feel good about the future of our country. Take a look. You tell me if we can recapture this type of civic dialogue in these dystopian times:

Photo by Gage Skidmore via Flickr