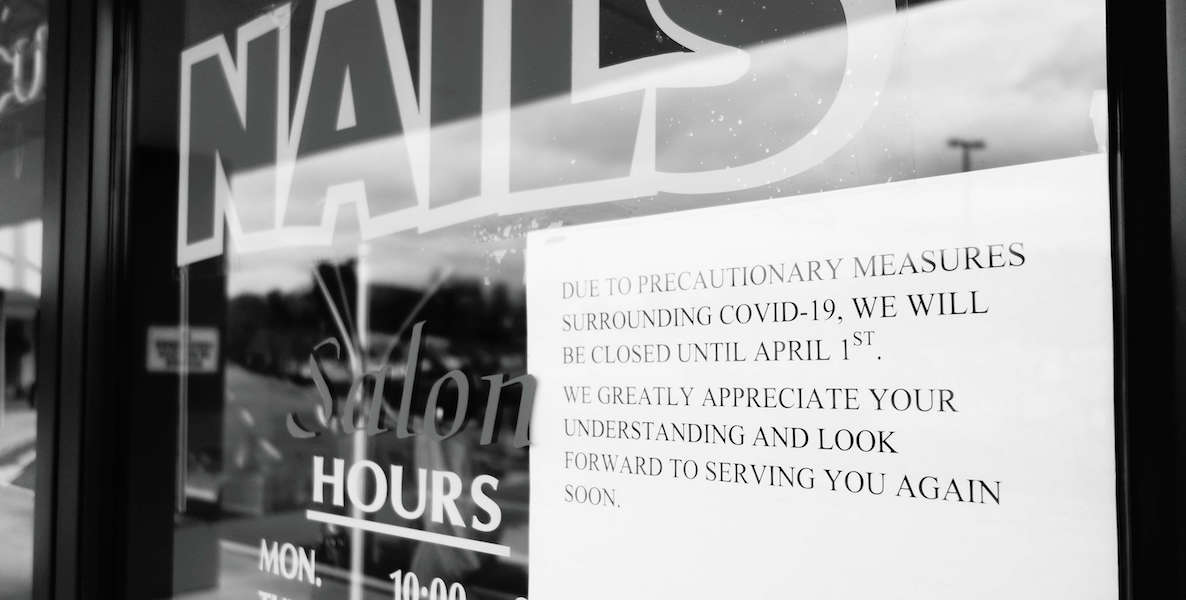

The Covid-19 crisis is wreaking havoc on Main Street small businesses across the United States, with millions of small businesses have shuttered for the duration of the crisis.

The hardest hit are Main Street enterprises living on the brink—restaurants, bars, coffee shops, barbershops, hair salons, auto repair shops, dry cleaners and others that provide face-to-face services.

These entities, usually sole proprietorships or businesses with fewer than 20 or even five employees are running out of cash or already broke. Micro businesses owned by people of color are most at risk, given decades of redlining and structural racism in the financial industry.

in a nutshellThis story

The widespread collapse of local-serving businesses means that Americans will return to downtowns, commercial corridors and Main Streets that are only partially occupied; the buildings will be intact (unlike after a hurricane or flood), but the scale of commerce being transacted will be radically circumscribed, with two or three out of five businesses gone and the remainder operating at a limited scale due to health protocols.

If left unchecked, substantial vacancies and diminished commerce will precipitate a series of domino effects—on consumer confidence (given the central role that these places serve as hubs of community and civic life); on owners of commercial real estate (given the cessation or diminution of rent payments); and on tax revenues (given the disproportionate role that business districts play in local fiscal health).

Each of these factors alone will slow an eventual recovery, together they will make it exceptionally painful.

As the economy shifts from rescue to re-open, Congress and communities alike need to focus on places rather than just products in the design, finance and delivery of recovery aid. To that end, we propose that communities establish (and the federal government support) Main Street Regenerators to speed the revival of our business districts—downtowns, town centers, commercial corridors, university districts, classic Main Streets themselves—where community-serving enterprises congregate and co-locate.

The notion that a quick revival of Main Streets will be driven by millions of individual small businesses acting on their own defies the laws of finance. Owners of collapsed small businesses will suffer from damaged credit and deep reductions in their savings and investments (and those of their family and friends), making it difficult to restart their enterprises.

In most communities, these regenerators will build upon and bulk up existing intermediaries and institutions which already further the operations of these districts: merchant associations, business improvement districts, community development corporations, entrepreneurial incubators and accelerators and Main Street programs.

Regenerators will also coordinate and connect with the wide variety of other organizations which are critical to small business success and the revival of nodes of commerce: city and town governments, anchor corporations, hospitals Help local businessesDo Something

Main Street Regenerators are needed to accelerate, and share the benefits of, the economic recovery. The notion that a quick revival of Main Streets will be driven by millions of individual small businesses acting on their own defies the laws of finance. Owners of collapsed small businesses will suffer from damaged credit and deep reductions in their savings and investments (and those of their family and friends), making it difficult to restart their enterprises.

This situation is only marginally more manageable for businesses that remain open, whose ability to re-stabilize will depend on the establishments and institutions surrounding them. Alternative financial products that are low-cost and have flexible terms are needed for both groups, but do not exist at scale.

Given these constraints, a failure to act at the geography and scale of place rather than at the individual business level will make these nodes of commerce vulnerable to vacancy and disrepair, purchase by speculative landlords or conversion to uses (e.g., Big Box retail) which are not aligned with the values or priorities of the communities they serve.

We need aggressive action to both preserve and reimagine what is special about our communities, as well as to prevent these worst-case outcomes.

Five Key Functions of a Main Street Regenerator

Main Street Regenerators will perform five separate functions, across urban, suburban and rural communities.

1. Regenerators will help refill vacant buildings.

A vibrant and diverse mix of uses and activities (e.g., residential, retail, office, services) is an essential ingredient of successful Main Streets. A Regenerator’s critical role will be to work with landlords to fill spaces that have been emptied by failed businesses.

This could cover a broad range of sectors. For example, as of the writing of this article, the House of Representatives is considering support for a surge in workforce development participants. This could create opportunities for converting and re-using existing commercial real estate for educational purposes, or for on-or-near-campus housing. Such transitions will require partnerships with private and nonprofit actors, which would be facilitated by Regenerators.

Beyond workforce development, a Regenerator should consider other uses that align with community needs and priorities including, but not limited to, pop up restaurants, shared kitchens, maker spaces, arts and cultural activities, health clinics and beyond.

2. Regenerators will coordinate the reconfiguration of the streetscape to align with the new possibilities and challenges of the COVID-19 crisis.

The persistence of social distancing will require merchants to provide curbside pickup and, in the case of restaurants and other food services, outdoor dining. The loss of small businesses might open up the potential for parklets, within vacant lots and alleyways. Diminished vehicular traffic will enable more pedestrian and cycling opportunities as well as the programming of public spaces.

These place-making activities are already happening and must become a new norm. Each must be carried out in close consultation with real estate owners, merchants, consumers and the local government, offering the potential for communal charettes and innovation. Achieving these possibilities requires coordination and focused institutions, a role that we see Regenerators playing.

3. Regenerators will provide common services for small businesses that are located along the same commercial corridor (or even throughout a mix of business districts).

The Regenerator would start by procuring goods and services that are needed by all businesses. The purchase of shared outdoor seating or deep cleaning services in bulk, for example, would reduce costs and ensure compliance with new health protocols. The organization would also ensure access to high-speed internet for all businesses as well as help each business to design their own websites and engage in digital sales.

The Virus in the City seriesRead More

There are also long-standing examples of food halls and farmer markets (e.g., York, Pennsylvania’s Central Market) that leverage a common footprint while fostering individual entrepreneurialism. Cooperative examples in Europe and across the rural United States should also be explored as models.

4. Regenerators can act as master tenants within business districts.

Given the collapse or declining revenues of small businesses, individual tenants will find it difficult to continue to pay existing rents and fees on common maintenance areas. By becoming a master tenant for either all or a substantial portion of a business district, Regenerators can ensure that key nodes of commercial real estate are maintained at a high standard of quality and the setting of rent levels are aligned with the extraordinary nature of the Covid-19 crisis, where revenue flows will be dramatically circumscribed for an uncertain period of time.

In a subset of business districts, particularly those located within disadvantaged urban neighborhoods, Regenerators can work with public land banks, community development corporations and community land trusts to acquire buildings and land at scale. This will enable communities to overcome the fragmentation of ownership (and the rise in absentee interests) which has often thwarted local ambitions around expanding affordable housing and building Community Wealth. The shift to unified ownership of urban and rural business districts could enable legal structures and governance arrangements that enable small business owners to participate in the value appreciation that naturally occurs when their formerly disinvested communities gain a foothold in the economy.

5. Regenerators can enhance access to capital for individual businesses and the district as a whole.

To this end, it will work closely with traditional financial institutions, alternative lenders, investors and local relief funds to be ready sources of fit-to-purpose products, debt as well as equity instruments. It will need flexible operating resources to perform the other functions described above, sourced, in part, from federal investment, revenues generated through ownership of certain properties (e.g., parking garages) and services provided to certain users (e.g., housing developers, community colleges).

In this sense, we envision Regenerators functioning similarly to many chartered nonprofits, which are funded, in part, by the public but operate largely independently.

We need aggressive action to both preserve and reimagine what is special about our communities, as well as to prevent these worst-case outcomes.

In carrying out these functions, Regenerators will play a variety of roles. They will share costs, spread risks and scale across communities. They will act as bridges between the current relief period (when the health threat is still real and ever-present) and the future recovery period (when a cure or vaccine has been invented and uniformly deployed). They will also act as hubs to consolidate networks of residents and public, private, civic and community stakeholders, ensuring the seamless exchange of ideas that can drive innovative practices, local business expansion and inclusive growth.

We envision Regenerators becoming a solid foundation for organizations that focus on seeding and incubating entrepreneurs across a diverse set of sectors. Many vibrant commercial corridors already contain a healthy mix of business support organizations, which provide the farm team for the next round of small businesses to occupy commercial real estate space.

Cincinnati’s Over-The-Rhine neighborhood, for example, already boasts Cintrifuse (a hub that connects venture capital, mature corporations and emerging start-ups) as well as MORTAR (a resource hub for growing Black-owned businesses). We see Regenerators enhancing these existing efforts as well as expanding intermediaries similar to these so they become the vehicle for creating thick and textured ecosystems for identifying, nurturing, supporting, mentoring, and capitalizing small businesses and local development efforts.

What this Means for Federal Policy

Federal support for Main Street Regenerators will be critical. This can be provided by designating these entities as eligible recipients under existing and new federal programs. Senators Booker and Daines and Representative Kildee have proposed a Small Business Local Relief Program to provide $50 billion in direct assistance to cities, counties and states. Support for Regenerators would be a natural fit for this new program.

Regenerators will need varied kinds of capital to realize Main Streets’ full potential, including operating support, resources to provide common services and rent stabilization, patient capital for the leasing and acquisition of real estate and access to market capital for the renovation of existing buildings. Beyond this program, direct appropriations, targeted tax assistance and even targeted credit enhancement through SBA or FHA products could also be considered.

The federal role will extend beyond capital. The scaling of Regenerators will depend on the rapid codification and sharing of new models and norms as they emerge. Great care will be needed to differentiate between the evolution of Regenerators along Main Streets which, prior to the Covid-19 crisis, were operating at full capacity and those located in distressed urban, suburban and rural communities and neighborhoods, where longstanding issues around vacancies and local capacity were major impediments to revival.

The bottom line is this: the revival of Main Streets and Main Street businesses—essential to the broader revival of the U.S. economy—will not occur through the relief programs and lending mechanisms that have been deployed to date. The next phase of Covid-19 recovery must include support for business districts and small businesses alike.

Main Street Regenerators, by building on existing institutions and employing new functions, could be a vehicle for reviving the places that define our communities. They could help catalyze not only the regeneration of places that are central to community life but also the reimagination of the uses and activities that these places concentrate.

Bruce Katz is the director of the Nowak Metro Finance Lab at Drexel University, created to help cities design new institutions and mechanisms that harness public, private and civic capital for transformative investment. Frances Kern Mennone is director of strategic partnerships at Cross Street Partners. Michael Saadine is a real estate and social impact investor. Colin Higgins is a program director at The Governance Project.

Photo courtesy Katherine Rapin