Philadelphia author Liz Moore’s fourth novel, Long Bright River, was published earlier this month and has critics swooning.

The Washington Post described it as an “extraordinary new crime novel” and a “wonderful thriller.” The New York Times even made it the inaugural pick of its new book club column, Group Text.

The Washington Post described it as an “extraordinary new crime novel” and a “wonderful thriller.” The New York Times even made it the inaugural pick of its new book club column, Group Text.

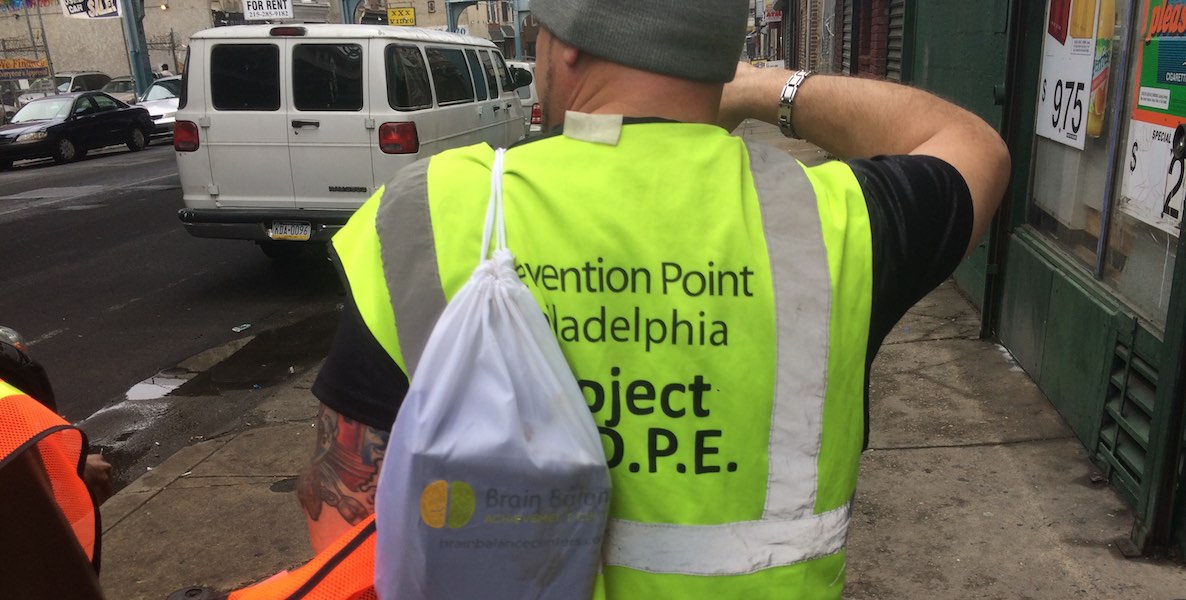

The literary thriller, already a New York Times best-seller, is set in Kensington against the backdrop of the opioid epidemic and provides just the sort of meaty topics—sisterhood, police corruption, addiction, redemption—that book clubbers will devour while hashing out the whodunnit’s twists and turns about two sisters (one a cop, one an addict) and their different paths.

Moore, a 36-year-old Massachusetts native whose own family has dealt with addiction, carefully acknowledges that she’s a “respectful visitor“ to the Kensington section of the city, having moved here from New York City about 10 years ago. But she has compassionately presented a cast of characters in the 482-page book that are nuanced and neither entirely “good” nor “bad.”

One exchange in her novel has an older woman explaining chess to the main character’s son. The boy wants to know which pieces are the “bad” ones. The woman responds: “They’re bad and good both, all the pieces.”

This Yin-Yang principle can be seen in Moore’s characters, including Michaela “Mickey” Fitzpatrick, a morally guided, emotionally guarded patrol officer in Kensington, and her younger sister, Kacey, an emotionally open and vivacious addict and sex worker who Mickey frequently observes while on patrol.

We caught up with Moore, who’s also a creative writing professor at Temple University, by phone to discuss Long Bright River and her writing process.

Sarah Jordan: When you moved from New York City to Philadelphia in 2009, of all stories to capture your imagination, why this one?

Liz Moore: I was new to Philadelphia and was looking for ways to get involved in community work.

A friend of mine, Jeffrey Stockbridge, was doing a photo project and invited me to do interviews of some of the subjects. [His work photographing those affected by drug addiction and prostitution along Kensington Avenue began as a blog, but eventually became a fine art book by the same name, Kensington Blues.]

I went out with him a handful of times to Kensington. Through that work, I became engaged and was going back on my own—including doing volunteer work with St. Francis Inn [a Franciscan, Eucharistic ministry that works with the area’s poor and homeless]—where I led free writing workshops at the day shelter, the Thea Bowman Women’s Center.

All of those experiences combined to inspire the setting for the book, but the emotional pull for me is my own family’s history of addiction. That’s what kept me going.

And since the publication of the book, I’m understanding the real scope of how widely addiction touches families throughout the U.S.

I’m getting a lot of early response from people who suffer from addiction or are in recovery or have family members. It’s meaningful to me.

I’m not interested in painting a completely bleak portrait of life. Life is a pretty even balance of hope and despair, so to drift too far in either direction would feel unrealistic.

SJ: When you were working on this book, how big was the opioid crisis? Were you shocked by what you saw in Kensington?

LM: I was writing it in 2017 at the peak, which is when the book is set. 1,217 people in Philadelphia died of overdose that year.

It’s a careful balance between feeling moved by what I saw, recognizing the element of human suffering in the neighborhood because of the scope of opioid use, but also wanting to leave room for hope in my book.

Hope is another emotion I have often in Kensington. I’ve met people who have successfully gotten into recovery and met people doing wonderful, generous work in the neighborhood.

SJ: Did you ever have misgivings about taking words and images from the people of Kensington to use for your book?

LM: I certainly entered into the project with the feeling that I had to take a lot of consideration on how to write respectfully about a neighborhood to which I was an outsider and visitor.

I’ll also say that I did not base any of my characters on individuals. The sites in Kensington in my book were also fictional, even the geography is slightly misrepresented in the book.

My primary focus on the work was as a piece of fiction, so I held two feelings in my mind constantly: one, a feeling of responsibility about representing a real place fairly; and two, wanting to talk about addiction in a new, more realistic way.

From opioid dependenceGet help

LM: I’m willing to bend the rules a bit in fiction, but I also think knowing as much as I can about the facts of police work was helpful to me as a writer.

I learned a lot from talking to several different police officers, one of whom took me on a ride-along in Fishtown. The hours spent with him asking about what happens from the start to finish on a shift was invaluable and provided an opportunity to learn about the small details that would have been difficult to get otherwise.

SJ: Your book includes plot points based on police corruption. What did you think about the September 2019 Inquirer story about the misconduct of 27 terminated officers?

LM: It confirmed to me what women said about some policemen’s conduct. There was always a whisper network. I’m happy to have professional journalistic confirmation.

SJ: Has being deeply immersed in this world shaped your opinions on safe injection sites and harm reduction theory?

LM: I’ve said on the record that I’m a proponent of harm reduction efforts and safe injection sites. There’s been a long battle over one in Philadelphia, but our first order of business is keeping people alive, because the rest is useless without life saving measures.

SJ: After all the time with this book and subject matter, how did it change you?

LM: It takes me a long time to write a book. I tend to publish one every four or five years, so I don’t know whether it is writing the book that changes me or whether it’s the changes that happen over the course of that time: I had a baby, I moved, had another baby, got a job.

One specific thing that changed over the course of writing the book is that as a society we evolved. When I first entered the neighborhood a decade ago, I was not well-versed in MAT [medication-assisted treatment, which combines behavioral therapy and medications to treat substance use disorder]. Over the last decade, there’s data showing opioid use is a different species of addiction so that long-term use of medications such as Methadone or Suboxone is necessary and useful to get into permanent recovery, along with ongoing therapy.

SJ: I don’t want to give away spoilers on how the story ends, but what are your thoughts on redemption while also keeping the story realistic?

LM: It felt right to not leave the characters completely hopeless. I’m not interested in painting a completely bleak portrait of life. Life is a pretty even balance of hope and despair, so to drift too far in either direction would feel unrealistic.

Correction: An earlier version of this story gave the wrong name for the day shelter where Moore did workshops. It is the Thea Bowman Women’s Center.

Photo courtesy Maggie Casey